Consciousness

[This topic is treated in Modes of the Finite, Part 3, Section 2. Chapters 1-3.]

5.1. Evidence for consciousness

There are those, like Gottfried Leibniz, who hold that all beings, even inanimate ones, are conscious; but since, as we will see, consciousness implies that the being cannot be in itself limited quantitatively, then unless we have evidence that something is conscious, we should assume that it isn't.

This is simply an application of a general principle in science, and it is based on the attempt to pick out the cause (the true explanation) from the many explanations that are internally consistent. The principle is known as "Occam's Razor," because it was first made explicit by William of Occam (1300). It is called a "razor" because you "cut away" all the speculative explanations that could be true but aren't necessary in order to explain the observed data. Thus, if the properties (operations) of a body, even a living body, can be explained without saying that the body is conscious, then the scientist will explain them as non-conscious (until some evidence comes along forcing him to admit them as conscious).

The reason some people call all living beings (or even all beings) conscious is that they react selectively to certain aspects of the environment. Sensitive plants have leaves that droop at a touch, the Venus's flytrap closes its leaves when a fly lands on it, heliotropes' flowers turn toward the sun, and in general plants grow toward the light, and so on.

But we have reactions to the environment that do not involve consciousness. The iris of our eye opens and shuts depending on the amount of light falling on it--and we are totally unaware of doing this. Our liver and spleen secrete their fluids on the presence of food in the stomach--and yet we are not conscious of anything being done by these organs. So if in us there are reactions, and very definite reactions, but unconscious reactions, to the environment, then it is possible for a body to react selectively to the environment without being conscious of what it is doing. Hence, we should not take selective reaction to the environment as the evidence that proves consciousness in a being.

What then will count as evidence that some body is conscious? Each of us knows that he himself is conscious; and each of us is aware of what aspects of himself are the faculties of consciousness: our eyes, ears, nose, mouth, skin (for touching), together with the "processor" of our brain--in general, the nervous system. When something is wrong with the nervous system or one of its organs, we lose consciousness.

We can conclude that other human beings are conscious, because (a) they are the same kind of thing that we are, and (b) they talk to us and describe what is going on within them--which is really inexplicable if they are not also conscious.

But since animals also have nervous systems and brains and other organs very closely analogous to ours, and since, though they do not talk, they exhibit behavior which is very similar to ours when we are conscious (such as motion in sleep, as if dreaming), then the more reasonable theory is that they are conscious, even though we can never get inside them to find out.

Of course, it is not really our task (even if it could be accomplished) to find out which bodies are conscious and which aren't, but to discover what the nature of a conscious body is, based on an analysis of consciousness itself, and the implications of this with respect to how the conscious body must be organized.

WARNING

We are going to be talking about what is in fact spiritual here, so be prepared for some rough going.

But we have to have some idea of what we are talking about, if we are going to investigate it; and unfortunately, the waters have been muddied, not only by people like Leibniz, but more especially by modern psychology, which defines consciousness either as any selective reaction to the environment (which would make sensitive plants conscious, as well as reactions like the opening of the iris of the eye), or any reaction to the environment involving the nervous system. But even then we become "conscious" of all kinds of "subliminal" things that we aren't aware of in the slightest; and I fail to see the meaning of "consciousness" when it is no different, really, from any other complicated unconscious act, like the reaction of your liver to food in your stomach.

Now this is not to quarrel with psychology for defining consciousness as it does; it has its own purposes, and the term as so defined suits them. But such definitions are not useful for us, because we are not interested in how what is called "consciousness" operates, but in what this act implies about the structure of the conscious body; and it turns out that the aspect of consciousness that is problematic is the one where you not only react, but know that you're doing so. What kind of an act does this have to be in order to be able to do this?

If the following definition sounds weird, I'm sorry. We're in a weird area of investigation.

DEFINITION: Consciousness (a) an act by which a being reacts directly to its own activity; it is (b) an act which reacts directly to itself. It is (c) an act which contains itself within itself. It is (d) an act which is transparent to itself.

These are four complicated ways of describing abstractly what is going on when, for example, you are aware that your hand is getting hot. Your hand is reacting to heat; but you react to the "being heated" of your hand when you become conscious of getting hot. If your hand just gets hot, then the act is unconscious.

The definitions are actually different ways of formulating this idea. Definition (b) spells out explicitly what is meant by "directly" in definition (a); the being reacts to its activity because the act reacts to itself. Definitions (c) and (d) spell out in different ways what is meant by "an act's reacting to itself" in (b).

The way we are going to approach an analysis of consciousness is this: First, we will try to show that the "reaction to the reaction" (the being aware of what the conscious act is) cannot be a different act from the conscious act--it is one and the same act. Second, we will see if it makes sense to say that a form of energy reacts to itself, and will conclude that this is nonsense. Third, we will conclude from this that a conscious act cannot be limited quantitatively, but must in some sense be spiritual. Fourth, this implies that the unifying energy (or activity) of any conscious being must be in some sense spiritual.

In the following chapter, we will discuss the lowest level of consciousness, and show how an act can be spiritual and yet also be a form of energy (with a quantity), and that sensation is such a form of consciousness; and we will call this type of spiritual-but- also-quantitative activity "immaterial" activity.

It would be a good idea to keep an open mind from here on, then; because we are going to follow the evidence wherever it leads us, and it leads us pretty close to contradictions at times. Our minds are built primarily to deal with energy (because the acts coming into our senses are all energy); but they are capable of dealing with the spiritual, if we don't let the scientific prejudice that "if it can't be measured, it doesn't exist" blind us to the conclusions demanded by the evidence.

Let us then consider the first question. Is the conscious act aware of itself, or are we aware of it (presumably by means of some other act)? So, when you see this page, is the seeing of the page one and the same act as the "knowing that you are seeing" the page, or does the "knowing" part of the complex act "see" somehow the "seeing"? (You can see how confusing this can get. Read carefully.)

The "second act" theory is preferable by Occam's razor, because then consciousness is explainable in terms of energy, whereas, as we will see, if the act is aware of itself, then it has to be basically spiritual--because it has to "do itself" twice without being a system of two interconnected acts.

The "second act" theory basically explains a conscious act as a kind of feedback loop. Let us take seeing this page as the example. When the energy from the light from this page gets into your eye, it sends electro-chemical nerve-impulses to a definite area of the brain (so far, no consciousness). If the energy in that area of your brain is above a certain level (the "threshold of perception") then that stimulates nerves in a different area; and it is the excitation of nerves in this second area which is the "I am seeing" aspect of the consciousness of the page.

So, the theory goes, you can react to the page without being conscious of it--if the only area of your brain that is active is the "visual" area itself. If that second area is active also, then you not only react to the page, you react to your reaction to the page, and you are conscious of seeing the page.

Let me say that there is no direct evidence that there is such a "second area" of the brain. It is assumed on the grounds (a) that it is the most reasonable explanation for the "awareness of being aware," and (b) that the energy in our brain actually goes through the whole brain in the form of waves of nerve impulses over the whole brain; and so even if some area can't be identified, it is quite possible that one exists (or is even some aspect of the waves themselves).

Now this "second area" theory of consciousness is, as I said, the preferred theory, if in fact it can explain all the data of consciousness. I am going to try to show that it can't; and so, however attractive it might be, it is false.

The first indication that there might be something wrong with it is that we actually do have cases where parts of our body react to acts of other parts of our body--but the second part's reaction does not make us conscious of what is going on in the first part.

For instance, when the stomach becomes active, the liver reacts by secreting bile. But this secretion of bile does not make us conscious of what the stomach is doing. When our blood-sugar level drops, we become hungry and are conscious of a feeling in the stomach, not in our bloodstream. Actually, the consciousness there is our consciousness of the stomach's activity in response to the drop in blood sugar; but the stomach's activity itself does not make the lowered blood sugar conscious as such.

The point is that a simple reaction to some other act within us does not necessarily make that other act conscious. This in itself is not evidence that the "second area" theory is false, but it is a clue that it might be.

What is necessary, then, in a "second act," whatever its nature, in order for it to render a "first act" conscious rather than a simple reaction?

Going back to your consciousness of the page you are reading, in order for you to be aware of your consciousness, your "awareness of your awareness" must not only be "aware" that your visual center is active, but it must be "aware" of what that activity is. That is, in order for your reaction to the page to be a conscious reaction, you have to know that you are seeing this page; that is, that the particular visual act you are having is the one of seeing this page and not seeing the Taj Mahal or an elephant.

Now a simple reaction to energy in the visual area won't do this. That is, a simple reaction means that some energy from the visual area travels to this "second area" and "turns on the light" there (i.e. stimulates some nerve there). The nerve in this second area just becomes active, that is all.

But what we need is for this "second act" to be active and for it somehow to "know" what caused it to be active. If in itself it is just an act, then the fact that it turns on when the visual centers turn on is not enough; then the fact that it is connected to the visual centers does not make this connection part of the act as such, in the sense of contained within it--any more than the pilot light telling you your stereo is on "knows" that the stereo is on. It goes on because the stereo is on, and we know this; but it doesn't.

So this is another indication that the "second act" theory is probably wrong.

There are, however, two ways in which this "second act" might possibly know what the "first act" (the act it is reacting to) is: (a) there could be a "third act" which reacts to the connection between the "first area" and the "second area"; or (b) the "second act" could be aware of itself, (and therefore aware of itself (1) as a reaction to something and (2) of what it was reacting to.)

Alternative (b), however, means that the "second act" reacts directly to itself--and we supposed that there was a "second act" in order to get around the difficulty connected with an act's reacting to itself. Hence, for the purposes of this hypothesis, that avenue is to be eliminated.

So the only reasonable explanation on the "second act" hypothesis (that can distinguish the consciousness-bearing "second act" from a simple pilot light that doesn't know what it is doing) is that there is a "third act" that reacts to the connection between the "first act" (reaction to the page) and the "second act" (reaction to the act in the brain's visual centers).

Unfortunately, however, this "third act" is just another pilot light. It turns on when both the visual centers and the "second area" are active, but it doesn't know either what is going on in the visual center (it just reacts to it) or what is going on in the "second area" (since it just reacts to this). It reacts when there is simultaneous activity in these two areas, but if it is a simple reaction, it doesn't know the connection between itself and these areas. Yet this is just what is needed for it to do its job of making the "first act" conscious. You can't be aware that you are seeing the page without knowing somehow that the "awareness of the awareness" is in fact the awareness of seeing the page.

This "third act" which simply reacts to the interconnection of two other acts would be analogous to your making a motion to turn over in the middle of a deep sleep. Your brain is reacting to the bad situation of being in the same position too long and the fact that you are asleep, and doing something to correct it. But that doesn't mean that you are conscious at this time; and certainly the movement itself is not the consciousness of the two aspects of the situation.

But in the case of consciousness, what this "third act" must do is make the "second act" aware that it is a reaction to the "first act." But if it simply reacts to the first and second acts, it can't do anything to either of them; they act on it; it doesn't act on them.

And really, wasn't that the problem with the "second act"? It was supposed to make the "first act" conscious; but it was simply turned on by the first act, and so couldn't do anything to it. So by the introduction of a "third act" we have come no nearer to solving the problem.

Of course, if this "third act" is aware of itself (if it knows that it is caused by the "first and second acts") then it can do the job; but then again we have to have an act that reacts directly to itself.

Since the problem with the "third act" leaves us with the same difficulty as the one we had with the "second act"; and since this difficulty is in fact the problem we had with the "first act" itself (how can an act be directly aware of what it is doing?), then to introduce a "fourth act" or a "fifth act" is going to get us no closer to a solution.

Hence, we can conclude the following:

Conclusion 1

Our conscious reaction to anything cannot be accounted for by an additional activity which reacts to it. An act of consciousness must be capable of directly reacting to itself.

Thus, until someone can show how a "second act" can not only be a reaction to the "first act" but know that it is one and also know what it is reacting to--without directly reacting to itself--then we will assume, by Occam's razor that these "second acts" and "third acts" don't exist, and all there is in consciousness is the "first act," which somehow or other not only acts, but acts on and reacts to its own activity while it is at it.

5.4. Consciousness as double itself

The question now is what kind of act consciousness is, if it is in one single act both "awareness of X" and "awareness of the awareness of X."

It doesn't look, at first sight, as if it could be a form of energy, because the act seems to happen twice at the same time, without being more than one act.

There are two ways we could confirm or refute this: First, we can analyze it, to see if there is a contradiction in having a form of energy which "duplicates" itself in this way; and if there is, we can conclude that the act, based on this analysis, can't be energy. Secondly, we can argue that, if it is in fact energy, then it should be detectable, and we should be able to figure out an experiment by which it could be detected. If it can't be detected, then it must be some other kind of something than a form of energy (i.e. it must be a spiritual act).

To take the first line of reasoning then, what we are going to do is apply what is called the reductio ad absurdum (reduction to absurdity) form of argumentation. What this type of argument does is this: You suppose (for the sake of the argument) that a certain statement is true. You find out what logically follows from this statement (that is, what must also be true if the statement is true). If that conclusion turns out to be false, the original statement also must be false.

For instance, I suppose for the sake of the argument that I never learned to write. But then this book would not have been written, and it would be impossible for you to be reading it. Therefore, it is false that I never learned to write.

To apply this to the present case, let us consider carefully what "being aware" and "being aware that you are aware" entails. When you see this page, the act of seeing the page (the very act of [consciously] reacting to the page) is totally aware of itself. That is, you not only are aware that your eyes are "turned on," but that they are seeing the page with these words on the page, that they are seeing it with such-and-such a degree of clarity, concentration, and so on. The whole of your act of "being-conscious-of-this-page" is within the act of "awareness-of-the-awareness." You may not know all about the page, but you know all about how the page appears to you.

So whatever this "awareness of the awareness" is, it contains all of the act of seeing the page within it. It would have to do this, because it makes the act of seeing the page conscious; without the "awareness of the awareness," you would have a simple reaction to the page, as we sometimes react to things that we don't really notice (as when we are driving and mulling over some problem, and have stopped for the red light before we realize even that we saw it). Now if the act of "awareness of the awareness" is analogous at all to the act of seeing, then it is a reaction of some sort to this act of seeing (which is why we developed the "second act" theory, you remember). But then the "awareness of the awareness" is a reaction to the whole of the act of seeing, of which it is the "conscious" dimension. But the act of "awareness of the awareness" is one and the same act as the act of seeing.

This means that the act really reacts to itself. That is, the "awareness of the awareness" is a real aspect of the act (and not just a name we put on it), because the act is really different below and above the threshold of perception. And it reacts to itself in such a way that the "awareness of the awareness" contains within it the whole of the act it is reacting to--but the whole act is itself.

The act of consciousness contains the whole of itself within itself--it contains its whole self as just one part of itself.

That is, the "awareness of the awareness" contains the "awareness" (the seeing) as just one part of the "awareness of the seeing"; obviously, the "seeing" aspect is less than this additional awareness that the act is seeing the page. Yet the "seeing" is identical with the "awareness of the awareness"; there are not two acts here, or we are in the "two-act" theory, which makes consciousness impossible.

And this is confirmed by the fact that the "seeing" contains within it the "awareness of the awareness," or it wouldn't be seeing, but just a reaction. So the "awareness of the awareness" is just one aspect of the total act of "seeing the page."

That is, it is purely arbitrary which of the "aspects" (the "seeing" or the "awareness of the seeing") is the container and which is the containee. Each contains the whole of the other within it.

But that makes the act greater than itself.

But this does not seem to make sense.

I told you we would be skirting pretty close to a contradiction. Let us look at the act as reacting to itself, and we will see what is going on here. If the act is a form of energy, then in order to react to itself, it has to act on itself. But with energy, this means to give up energy. Then it has to give up all its energy (because it reacts to the total of itself); and it gives it up to itself--which means, of course, that it doesn't give it up at all, which in turn means that nothing happened. If it doesn't give up energy, it doesn't act, but if it gives it up to itself [directly now, not through a feedback loop], then it doesn't really give it up, in which case, no action takes place.

So if consciousness acts on itself, it has to have more energy than it has.

And this doesn't seem to make sense either.

That is, if the act really acts on itself, then it has to add energy to itself, which of course is impossible, because then it would have more energy after the "addition" than before, without getting it from anything but itself. But that is absurd. Heat can't raise its own temperature; because there's only so much heat to begin with. If the temperature rises, this has to be from some outside source. Hence, if energy can't add anything to itself, then it can't really act on itself or react to itself. Therefore, the act of consciousness can't be a reaction to itself. But it is.

Nor does this seem to make sense.

But--the act happens, and it does contain itself within itself (or it does react directly to itself, without going through some feedback loop); and so it is not really a contradiction.

Conclusion 2

The act of consciousness cannot be described quantitatively. It is not a form of energy.

All of the difficulties we got into, if you look back at them, turned on the fact that the act had to be more than itself; but "more" is a quantitative term. If there is no "greater" or "less" connected with the act, the problem disappears.

5.4.1. Confirmation: consciousness as not energy

Now let us take the second line of reasoning, and see if we can confirm the theoretical conclusion we came to. If consciousness is not a form of energy, then obviously it can't be detected as energy. But if it is detectable as energy, then obviously, our analysis above has been faulty.

Now in fact many psychologists do not bother with a "second act" theory of consciousness at all, but simply say that the energy-output of the brain's nerves is consciousness. That is, they say, "What's all the fuss? When these nerves are active above a certain level, we call that activity 'consciousness,' that's all; why fool around with 'second acts that are supposed to react to first acts'?"

From an experimental point of view, I suppose this is legitimate. If consciousness occurs when these nerves are active (whether naturally, or directly as by an electrical probe introduced into the brain at that point) and if it doesn't occur when they aren't; and if the consciousness becomes more vivid the more active the nerves are, then what more do you want?

Remember, the fact that something happens does not make it self-explanatory.

The experimentalists' reaction is like the ordinary person's reaction to the physicist who wonders why things fall down (and not up, and fall faster and faster and not at a steady speed). The ordinary person is apt to say, "Because that's the way things are, that's all"; while the physicist answers, "Of course, but why are they this way? It violates the First Law of Motion if nothing's making them act this way."

Similarly here. The experimental psychologist is not interested in the implications of what "knowing that you know" has for consciousness; he's content when he's found the area of the brain in which the consciousness occurs, and can examine the measurable activity going on. Whether that measurable activity is or can be the whole story doesn't affect his particular investigations, and so is "just the way things are" as far as he is concerned.

It is legitimate for the psychologist not to pay attention to the problem. But he is overstepping his evidence if he says that there isn't one. What our purpose here is is to show that consciousness can't be explained as a form of energy (measurable activity), let alone the electrical output of the nerves.

First clue

Different forms of consciousness (seeing, hearing, etc.) have identical forms of nerve-output.

The only difference in the output of the nerve energy in seeing and hearing is the place in the brain where it happens. The nerves in those two areas are even identical. But if the nerves and the energy-activity are identical in both cases, then why are the conscious acts different in kind? That is, the energy is not different in kind; but the consciousness is. That doesn't make sense if the consciousness is nothing but the energy.

So you see, it isn't straightforward, at the very least, that consciousness is "simply" the electrical activity of the brain's nerves.

Second clue

A given act of consciousness does not seem to be absolutely tied to a given nerve-complex.

That is, there also seems to be some evidence that when damage has been done to nerves in a certain area of the brain (as in a stroke), destroying the consciousness associated with that area, it is sometimes the case that nerves in adjacent areas which hitherto did not have the function in question take over the function and restore consciousness. Nerves, once destroyed, are not replaced; but sometimes a person gets back lost consciousness by having different nerves do the job.

This is further evidence that the nerve-energy itself is not the consciousness. If it were, then these other nerves (whose energy does not change) would have the consciousness associated with them even before the taking over of the lost function. But they don't. How then can their output be consciousness if the same output is not and then is a given form of consciousness?

Third clue

Sometimes there is nerve-energy but no consciousness.

That is, it is well known that nerve-output below a certain level of intensity (the threshold of perception) is not associated with (or is not) consciousness, and above that level it is.

This implies that consciousness cannot be absolutely identical with the nerve-energy output; otherwise, there would be consciousness whenever there is output of the nerves.

Now at the threshold of perception, either (a) something real happens, so that the act is really different afterwards, or (b) we just choose to call the act "consciousness" afterwards, and don't call it that before. Alternative (b) is absurd, however, since below the threshold, we don't know what is going on (we may react, but there is no "awareness of the awareness"), and above it we actually know what is happening to us (we are aware of seeing, or whatever). This is a real difference.

Then alternative (a) is the only one that truly describes the situation. Now then, if there is a real difference, either (1) the difference is due to a "second act" which turns on, or (2) there is a real difference in the act itself. Alternative (2) is the only one possible here, since our previous discussion ruled out alternative (1).

Then the act after the threshold is passed is really different from the way it was before: it has that new aspect to itself called "consciousness," which involves the "awareness of the awareness," and is no longer a simple reaction.

Now then, if this other aspect is energy, then what this means is that the output is at this point transformed into two different kinds of energy: the nerve-output and "consciousness-energy."

In principle, this "consciousness-energy" aspect of the act is measurable, since it is energy--but we might actually be able to measure it, because we might not have instruments that can detect it.

So it looks as if we're stuck. True, no one has ever measured "consciousness-energy." But that could be either (a) because there isn't any, or (b) because we don't have the means to do so.

But even if (b) is the case, all is not lost.

But since there was just electrical energy below the threshold, then we can indirectly measure this "consciousness-energy," because (1) energy doesn't get created out of nothing (the first law of thermodynamics); and therefore (2) it would have to come into being by a transformation of some of the electrical output into this other form. Where else could it come from? This is the only possible source of the new energy.

But then this allows us to predict the following:

Prediction

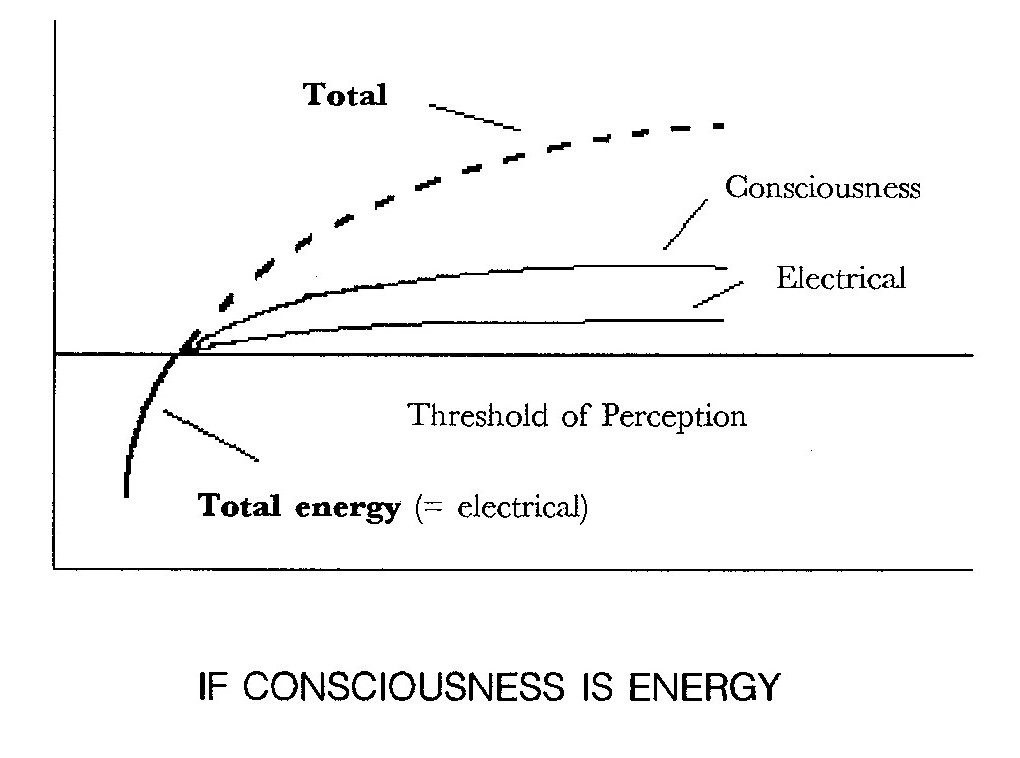

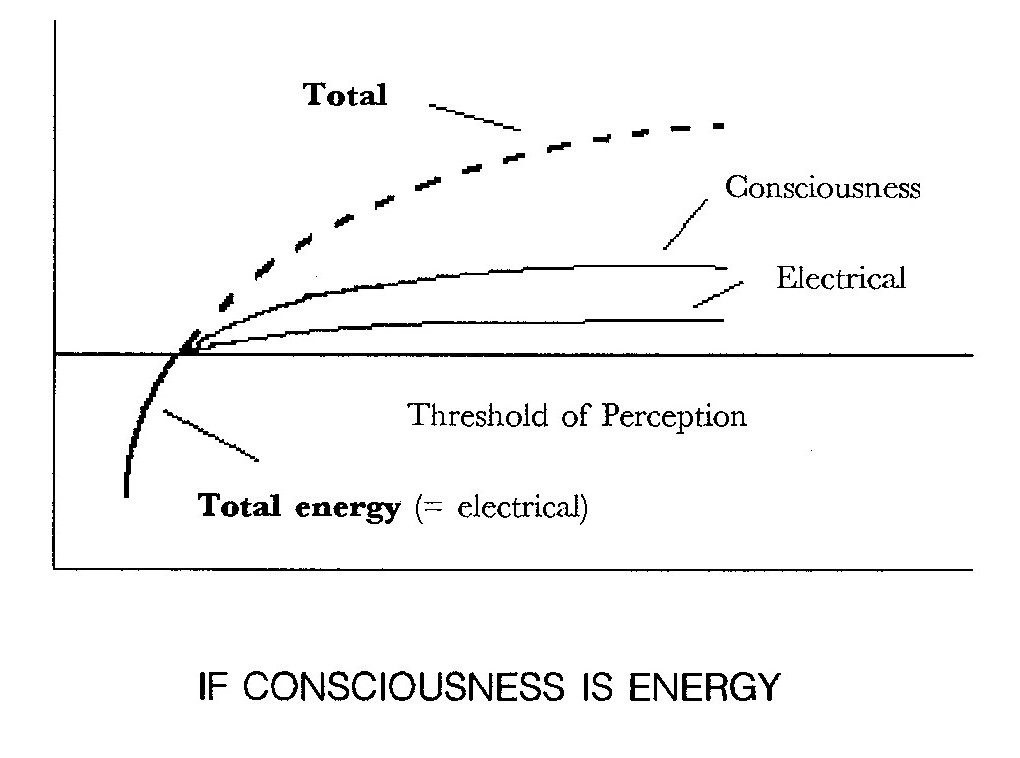

If the "consciousness" aspect of the nerve-output is a form of energy, then as the electrical output of the nerves increases from zero through the threshold and beyond, we would find a "flattening" of the rate of increase as the threshold is reached, and a decreased rate of increase thereafter.

The reason for this prediction is that at the threshold, the electrical output no longer is the total energy involved; the total energy begins to split into two different forms of energy ("consciousness-energy" and electrical); and therefore, the electrical output itself would not increase for a while and then would increase more slowly than before (because only a percentage of the input now is going into the electrical component).

Schematically, it would look this way:

The dashed line called "total" above the threshold of perception is a theoretical figure: simply the sum of the two energies beneath it; it is what the energy would be if it were all one form of energy. The solid lines represent what the real energies are--on the supposition that consciousness is actually a form of energy.

The point is that you don't have to be able to observe both the energies in order to check this result. If all you can measure is the electrical output of the nerves, then the discrepancy between the output below the threshold and the dashed line (what the output would be if it were all electrical output) will give you the amount of the "consciousness energy."

So if consciousness is energy, the electrical curve will not follow the dashed line, but will level off and give a shallower increase above the threshold of perception.

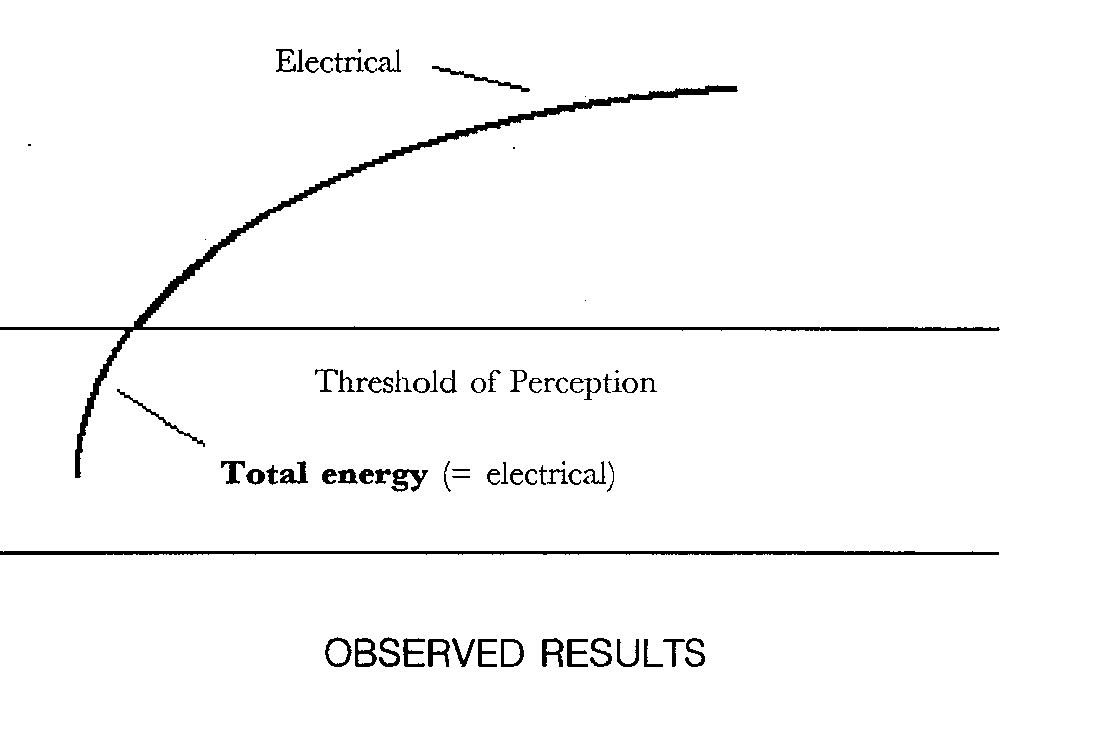

Now then, what does the electrical output curve of the nerves actually look like?

As you can see, there has never been observed any difference between the electrical output above the threshold of perception and what you would expect if there were no "consciousness energy" at all--which is one reason why experimental psychologists tend to say that consciousness is nothing but the electrical output. If, they argue, it is something else, then why can't we detect it?

But if it is, then what about the clues we talked about above? And what about our argument in the preceding section?

In any case,

Conclusion 3

If consciousness is something real, it takes no detectable energy from the nerves when it comes into existence.

In fairness, while the curve above represents what is observed, it isn't as simple as that. The output of a small area of the brain (which is what would have to be the issue here) really spreads itself over the whole brain; and isolating one small aspect of it is not in practice possible (since any given nerve is connected to millions of others, and "tracking" what happens to the energy that comes out can't be done).

So the graph just above is consistent with what is known from the nerves, but is not a graph of actual measurements. Hence, the best we can really say from observation of the nerve-output is that there is no evidence of any "consciousness-energy" rather than the stronger statement that "there is evidence that there is no 'consciousness-energy.'"

5.4.2. Consciousness as spiritual

So the two lines of evidence converge upon the same fact: consciousness is not something measurable. Some scientists would say, "Therefore, it doesn't exist." But if there's anything we have evidence for, it's consciousness; it, in fact, is the evidence for everything else.

But we argued back in the second chapter that there is no reason to say that something has to be measurable in order to exist. Quantity is not existence; quantity is just a limitation of a limitation of existence. Spiritual existence is at least theoretically possible-- and, in fact, the evidence for the existence of God (which I haven't given here) indicates that there is at least one spiritual act.

General Conclusion

Consciousness is a spiritual act.

That is, it is limited to being this act, but it has no "muchness" to it; numbers do not apply to it; it cannot be measured; it has no quantitative limit.

If the act is not quantitative, then one and the same act can contain itself within itself, because it can be doubly itself without really "adding" to itself at all.

Corollary

The act of consciousness "does itself" many times over in one and the same act.

This is confirmed if we notice something about the "awareness of the awareness." Are we conscious that we are "aware of being aware"? We must be; because everyone recognizes (with a little introspection) that the difference between consciously seeing the page and merely reacting to it is that when you are conscious of it, you know that you are seeing it.

But then the "awareness of the awareness" has an "awareness of the awareness-of-the-awareness" that is conscious of it, or the "seeing" would be conscious, but we wouldn't know that we knew we were seeing.

So it's not true to say that there are "two" acts going on here; there are at least three of them, each containing the other two as part of itself (and each, at least in principle, distinguishable from the other two).

But of course, this "awareness of the awareness-of-the-awareness" is also conscious, because you know that it is happening. That is, it's absurd to say that you don't know that you realize that you are conscious of seeing the page. So there are "four" acts, not one or two or three. But these "two" or these "three" or these "four"--and we could go on--are all one and the same act. There precisely isn't more than one.

This makes sense if the act is spiritual, with the result that numbers don't apply to it; and it makes no sense at all if the act is energy. If it is energy, then any "multiplication" of itself has to be outside it; and then we have not merely two, but three or four or five or more interconnected acts. So the "second act" theory was actually an oversimplification.

Hence, we can say this:

General characteristic of the spiritual

A spiritual act is totally transparent to itself; it is totally present to itself; it is totally within itself; it totally knows itself.

THEOLOGICAL NOTE

If God is a spirit, then there is nothing contradictory in his being a Trinity: that is, three acts, distinguishable in some sense, but actually just "ways of looking at" one and the same act. Just as the "awareness of the seeing" is in reality identical with the "seeing" (because there is no more than one act), it is also not identical with it in concept (because it is one of the "reduplications" of the act by which it is present to itself), so the "persons" of the Trinity are not the same as each other, but each is contained within the others and each is in fact "one and the same reality" (in the words of the Greek of the Nicene creed) as the other "two."

The "Father" is said to "generate" the Son. We could perhaps express this this way: the Father is the "act" which reduplicates itself. The Son, of course, would be the reduplication, which is, as spiritual, the same act--one and the same act--as the Father. The Spirit is said Theologically to "proceed" from the Father and the Son. If you wanted to use the analogy I am developing here, the Spirit would be the "reduplicating" (what the Father is doing in generating the Son--which is the Divine Act itself--and what the Son is doing "imitating" the Father as His "reduplication"--which is of course also the Divine Act); and so the Spirit is a kind of relation between the Father and the Son, or an "imitation" which is no imitation but is the identical act which is both the Father and the Son.

Why is God called a Trinity and not a Quaternity or a Quinity? If the Trinity is due to God as spiritual (and not necessarily as absolutely unlimited) then there is no intrinsic reason why he couldn't be called such; because a spiritual act "does itself" as many times over as you want to name. But Jesus referred to the Father and the Spirit, and called himself "one thing" with the Father and the Spirit. And so since he gave these three distinct names to God, and yet said they are "one and the same thing" (John 16 and 17, e.g.).

This is not necessarily an "explanation" of the Mystery of the Trinity. It does, however, show that it is not unthinkable for God to be only one God and yet be three really distinct "somethings" at the same time; because a spiritual act does really "do itself" over more than once.

5.5. The faculty of consciousness

If consciousness as an act is a spiritual act, then this means that it is "infinite" with respect to quantity. That is, as I mentioned earlier, this does not mean that it is God, because it is obviously limited in form. All "infinite with respect to quantity" means here is that, since quantity is a limitation, it is not limited on that level. That is, the idea that two and two are four is not twice the idea that one and one are two; it is just different.

But how are you to think of a spiritual act?

Understand this

The spiritual is to energy as colorlessness is to color. Number-terms do not apply to it.

What do I mean here? Colorlessness is not "no color" (which would be blackness), or "all colors combined" (which would be whiteness) or "a color, without specifying which one" (which would be a "color variable"). What "colorless" means is that color-terms do not apply to the object. Similarly, as I said above, what "spiritual" means is that number-terms do not apply to the spiritual object, and when you try to apply them--as we did above--you get contradictory results.

That is why in consciousness you have to say that there is not one act (as opposed to two or three), that it doesn't have parts (in the sense that one part is "outside" the other ones), that one act of consciousness is not greater or more powerful than any other, and so on. Every act of consciousness is different from every other one in the same sense that heat is different from sound or that dogs are different from cats; they are different kinds of acts, even though they all have the generic name "consciousness."

Of course, numbers do describe limits on energy; and the spiritual is beyond this type of limit--and so it can be called "infinite" with respect to quantity. Note that only God is infinite with respect to both quantity and form. Other spiritual acts have the limitation of form, and are a definite kind of activity, and so to say "spiritual" is not necessarily to say "absolutely infinite."

With that out of the way, then, if the spiritual is totally beyond quantitative limit, it follows that

Conclusion 4

The parts of the body that make up the faculty of consciousness cannot account for the act of consciousness.

Why? Because these parts are bundles of energy, having quantities. The eye, the nerves, and the brain cannot account for seeing as an act of consciousness--though they may be necessary for us to see. But insofar as they are energy, they cannot produce an act which is infinitely beyond their quantitative limits.

Yet it is clear that the brain and so on do produce the acts of sense consciousness, at least (we will take up the problem of what the "faculty" is for understanding and choosing much later). And since the parts can't be what is responsible for the spiritual act, then we can draw the following conclusion:

Conclusion 5

The activity organizing any faculty of consciousness must be (at least in some respect) a spiritual act.

The reason for saying "at least in some respect" is that, as we will see in the next chapter, the sense faculty has what you might call an "energy-component" whose function it is to unite the parts of the faculty; and so the organizing activity of the sense faculty is in one respect spiritual and in one respect material. But we will worry about making sense out of this later. For now, it is enough to say that something about any faculty of consciousness must be spiritual, and this "something" has to deal with the activity organizing the parts.

5.6. The soul of a conscious body

If a body which has consciousness as one of its properties has a spiritual act as one of its acts, and if this, as we just saw, implies that the faculty is organized with some kind of a spiritual act, then we can draw the following conclusion about the nature of the conscious body:

Conclusion 6

Any body which performs a conscious act must have a soul which is at least in some respect spiritual.

The reason for this is that the soul is the controlling activity of the whole body, the act which builds the parts into organs and faculties and which regulates the acts of these faculties so that it is the whole body which "really" acts. If the soul of a conscious body were merely a form of energy (however high the energy-level), then its faculty of consciousness would be infinitely beyond it (because the faculty is organized with a spiritual--or in part spiritual--act), and therefore the faculty would not be able to be dominated by and under the control of the soul, and the body would not act as a unit.

Hence, if an act of a body is in part spiritual, then the faculty to perform that act must be spiritual (at least in part) and the soul of that body must be spiritual (again at least in part).

The reason I say "at least" in part here is that a totally spiritual soul can be responsible for a faculty and an act that is only partly spiritual. What is greater can do less; the point is that what is less cannot do anything greater than itself. And in fact human beings, who have souls that are spiritual (and not "immaterial," a distinction we will see later) have "immaterial" faculties of sensation (which are only "in part" spiritual).

5.6.1. Consciousness and the computer

Can computers think, then? Not if by "think" you mean a conscious act. Computers are systems of energy, and don't even have any real unifying energy making them bodies, let alone having the spiritual unifying act that would make them able to be conscious.

Computers may be able to behave in much the same way as animals and other conscious beings; because much of what we call "thinking" and "perceiving" is simply reacting to the world around us and arranging and connecting those reactions. Computers, for instance, can be connected to photocells, and these photocells programmed to react to, say, printed words, which the program connects to voice synthesizers producing certain sounds when certain words are "input" through the photocells; and so the computer could be programmed to read this page--and, in fact, I have seen this happen. A blind woman I know had a computer on which you could put a page of text, and it would "say" aloud what was on the page. But it didn't see the page; it simply reacted to the marks. There was no "reaction to the reaction."

Similarly, computers now exist which are connected to microphones and voice-recognition programs, and these words connected to a printer, so that the computer will print out what you say into it, and even be able to distinguish (by context) "to, too, and two".

And it's not far into the future when computers will listen to what you say and talk back to you, just like HAL in 2001: A Space Odyssey. And there are already and will be computer programs that learn by erasing courses of action that turn out to be failures (as, for example, if the chess-playing program loses, it goes back over its moves and blocks out one of the moves it made, so that the next time it won't do the same thing).

But all of this, impressive as it is when you see it in action, does not mean that computers can think or are conscious. We do all these things when we think; but they do not define thinking; thinking is a conscious act, which knows what it is doing while it does it. And this is totally beyond the range of a computer. It can make marvelous connections; but it has no act which can "do itself" twice in one and the same act.

Beware of the pseudo-religion of science which says, "Well, maybe they aren't conscious yet, but give us time." What that is saying is that the argument above for the spirituality of consciousness is false (because it says that what consciousness involves is impossible--a contradiction--for energy). So the argument above has not simply proved that "we have no evidence for saying that consciousness is energy," it has proved the much stronger statement, "We have evidence that consciousness is not and cannot be energy."

In other words, to say that computers might become conscious in the future is analogous to saying that sometime in the future, it will be possible for water not to consist of hydrogen and oxygen, because "so far" we've just proved that there's no evidence for saying it's made of anything else. If you ever find water not consisting of hydrogen and oxygen, then the whole atomic theory is false.

No, this notion that, "Well, some day we'll figure out a way to make computers conscious," is pure dogmatism on the part of scientists who refuse to look at evidence that would indicate that there might be something that is real but not measurable.

Don't be taken in by this kind of thing. True, the theory above can be wrong; but until there is evidence against it, a reasonable person will take it as what the facts are.

HISTORICAL SKETCH

Plato (400 B.C.) certainly held that understanding was a spiritual act (since it got at the eternal, unchanging, invisible Forms); but he seems to imply that sensation or perceiving the changeable world was not spiritual (because our sensations change just like the world perceived by them).

Aristotle (350 B.C.) thought of consciousness as a kind of "becoming" of the thing we were conscious of, though not in a material way. That is, when we are conscious of a rock, the form or characterization of the rock (that is, the act the rock is doing as a rock) is within us, but without the matter; in other words, the mind imitates or performs the same act as the object (and so "becomes" or "is" the object); but the mind doesn't turn into the object, because the act is the act of the mind, not of the "stuff" the object is "made of."

St. Thomas Aquinas (1250) made the distinction we are going to make (and have hinted at) between the "immaterial" and the "spiritual," on the grounds that the "immaterial" did not have matter (which he rightly interpreted as limitation of form, not some "stuff"), but was "subject to the conditions of matter": individuality, time, and space. Spiritual acts like understanding, however, were "universal, timeless, and spaceless," and thus were purely spiritual. Our grounds for the distinction will be different, because of what modern science has taught us.

Descartes (1600) held that thought, which had nothing to do with "extension" (spatiality) was a spiritual act implying that the mind was a spiritual "substance" different from the body it was in. He held that sensations were in themselves simply mechanical reactions to things; animals were complex machines, with no spirituality about them at all.

The British Empiricists, Locke (1670) and Hume (1750), thought that they had successfully reduced all "thought" to combinations of sensations; and this, together with Descartes' exclusion of sensation from spirituality, led future thinkers to pooh-pooh the notion of spirituality altogether.

Immanuel Kant (1790) did say that understanding was an act different from sensation; but he believed he had proved that it was impossible to know whether anything spiritual existed--though we had to assume (or "postulate," as he said) that the human soul was spiritual in order to have ethics make sense.

Kant, then, was the one who made scientists think that it was a waste of time to pursue questions of spirituality--even though his analysis of why this was supposedly so was faulty.

Georg Hegel (1810), however, was the one who is most responsible for the modern world's suspicion of spirituality, because of his brilliant "description" of the world as the "consciousness of the Absolute becoming aware of Himself in the object He produces"-- which made everything simply consciousness (i.e. Divine consciousness) and consequently everything, including matter, spiritual. Those intelligent enough to follow Hegel's very difficult reasoning either got totally convinced by it, or felt that something was radically wrong with it, but couldn't put their finger on what--and so decided to forget about the whole thing.

Consciousness, in philosophy (not as in psychology) involves not only reacting to the environment, but realizing that you are doing so. The question is whether this act is a system of two acts, the "reaction" and the "realizing," or whether "they" are two ways of describing only one act; and if there is only one act, whether this act can be energy.

The conscious reaction and the realization cannot be two acts, because then the "realization," as separate, would not know what the "reaction" was, but only that something or other was active in another area of the brain. Nor would a third act reacting to the connection between the two do the job, because it would not realize what it is connecting. Hence, the act of consciously reacting to the environment must be one act, containing with in the realization of what it is doing. Consciousness, then is (a) an act by which a being reacts directly to its own activity; it is (b) an act which reacts directly to itself. It is (c) an act which contains itself within itself. It is (d) an act which is transparent to itself.

But such an act cannot be a form of energy, with a quantity which means it is "only this much and no more." First, if it is energy, then in reacting to itself, it would have to "do itself" twice, which would mean that, whatever its amount, it would have to be double that amount. Secondly, if it is a form of energy, it must somehow detectable. But (a) different forms of consciousness are associated with the same kind of nerve-energy, (b) sometimes consciousness "migrates" to an association with different nerves, (c) at low levels, the nerves produce energy but not the associated consciousness, and finally (d) if consciousness were energy, there would be a drop in the energy-output of the nerves at the threshold of consciousness; but no such drop is observed.

These two lines of reasoning prove that consciousness cannot be described as "only this much" of an act, or is spiritual and not energy. Consciousness is infinite with respect to quantity.

It follows from this that the faculty of consciousness (the nervous system), whose parts are all physical (i.e. made up of energy) must be organized in a basically spiritual way, or it would perform an act infinitely greater than itself.

By the same token, the soul of a body which is conscious must be in some sense spiritual, or it would not be able to build and direct a faculty which is organized with an act infinitely greater than itself.

And it also follows from the spirituality of consciousness that computers are not and will never be conscious, since they are simply systems of energy.

Exercises and questions for discussion

1. Why aren't Venus's Flytraps and sensitive plants (which respond by moving when you touch them) evidence that plants have sensations and so are conscious?

2. Why would it not be possible to be absolutely certain that there is something if your consciousness and being conscious-of-being-conscious were not one and the same act?

3. But since consciousness never occurs without the nerves in the brain putting out energy, doesn't this prove that consciousness is just that energy?

4. Doesn't the fact that if consciousness is conscious of itself it has to be twice itself without being more than itself prove that there's something wrong with our reasoning, not that consciousness is something weird?

5. If the soul of a conscious body, like an animal, has something spiritual about it, doesn't this mean that the soul will go on existing after the animal's death, and so there is a doggie heaven after all?