Sensation

[This topic is treated in Modes of the Finite, Part 3, Section 2, Chapters 4 and 5.]

The approach we are taking toward life is from the more limited to the less limited; and this poses a problem for us at this point. Thinking is actually somewhat simpler to analyze as consciousness than sensation is, because sensation is an act that is spiritual but also quantitative, which sounds like a contradiction in terms.

I can, however, offer the solace that, once we have got beyond this chapter, the sailing gets a little smoother. A little. So let us press on.

DEFINITION: Sensation is reactive consciousness: that is, acts of consciousness which are reactions to outside energy, or the integration, storage, and retrieval of such reactions.

One of the reasons that sensation has to have an "energy-component" is that a purely spiritual act cannot change, and so cannot be affected by anything outside itself. The reason, as we saw earlier, is that change is started by an instability, which is a discrepancy between the unifying energy and the total energy of the body. But that implies that the unifying energy has a definite quantity, because if it didn't, how could there be a "discrepancy"?

Hence, if we are to have consciousness that is not totally self-contained, so that we can consciously react to the world around us, then our consciousness has to have this peculiar "spiritual-material" characteristic.

DEFINITION: An act is immaterial if it is in itself spiritual, but is (in the same act) also a form of energy, with a quantity.

Sensation, then, is immaterial consciousness; and as we saw in the preceding chapter, this implies that the sense faculty is a faculty organized with an immaterial act, and the soul of the body which has sense consciousness must therefore be at least an immaterial soul.

Having given a reason why we have immaterial consciousness, we will approach the subject of sensation this way: we will give evidence indicating that sensation, though conscious, is a form of energy; and then try to show how it is possible for an act to be both spiritual and a form of energy. Finally, we will describe the act of sensation in terms of the various ways we react to different aspects of our environment (the so-called "five senses"), and then how we integrate, store, recall, and work with these reactions (the "internal senses").

6.2. Evidence that sensation is energy

Now then, what is the evidence that indicates that sensation, though consciousness, is indeed a form of energy?

First of all, a purely spiritual act cannot change, as I said above; yet sensations form a stream of varying impressions.

Secondly, sensations depend upon the energy in the nerves in the brain. When the nerves are active, sensation occurs; and which nerves are acting determines which type of sensation is going to be experienced. This could be simply a condition for sensation to occur, but it implies either (a) that sensation is affected by the brain's nerve-energy, or (b) that the consciousness and the nerve-energy are actually the same act. We saw in the last chapter the difficulties with (b) if you call sensation merely nerve-energy. What we are going to argue to is a version of (b) in which sensation has the nerve-energy as one of its "components."

Thirdly, sensations vary in vividness--and, in fact, vary in proportion to the intensity of the energy they are reacting to. (Actually, this variation is not straightforward, and is not quite what Weber and Fechner thought in their "law," that of a logarithm of the energy; but there is--as S. S. Stevens has shown--a rather more complex, but still mathematical, relationship between the perceived vividness and the intensity of the energy.)

It would be difficult to see how a purely spiritual act (in fact, a spiritual act in any sense) could vary in vividness without having a quantity in some sense; it would seem that an act which is the same but "more vivid," especially in some mathematically definable sense of "more," has to have a quantity.

But

It is nevertheless the case that sensation is an act of consciousness; because when you see or hear or whatever, you are aware of seeing or hearing; and we saw in the last chapter that this cannot be explained if the act is a form of energy.

The dilemma

There is good evidence that sensation is energy; and there is equally good evidence that sensation is consciousness, which cannot be energy.

Clearly here, we have an effect, not a contradiction, unless we have been misreading the evidence somehow. There has to be a way out of the dilemma.

6.3. The solution: sensation as immaterial

But how can something which can't be energy be energy? The answer, actually, lies in the nature of the spiritual. We saw in the preceding chapter that a spiritual act "does itself" many times in one and the same act, so that it contains itself within itself or is transparent to itself. We also saw that it was impossible for energy to "do itself over again" because this would mean that it would have to double itself; but its quantitative limit prevents it from being twice as much as what it is.

But if a spiritual act can duplicate itself without being two acts, there is no reason why one of its "duplications" could not have a quantity, so that the spiritual act could be both an act of consciousness and a form of energy in one and the same act. While is it impossible for energy to "duplicate itself" as consciousness, it would not be impossible to go the other way and have consciousness (which duplicates itself anyway) duplicate itself as energy. What is less cannot do what is greater, but what is greater can do what is less.

That is, if the act of consciousness called "seeing," for instance, "does itself" as the visual impression of this page, and also "does itself" as the awareness of this visual impression, that same act, since it is spiritual, could also "do itself" as a certain form of nerve-energy, with the quantitative limitation the nerve-energy has.

Now it could only "do" this quantitative "reduplication" of itself once, because, even though the act in itself is infinitely beyond the quantity which it "adopts"; still, once it has a quantity, it can't have a different quantity at the same time in one energy-act. Of course, however, there might be a system of interconnected energy-acts as the "reduplication."

So a spiritual act can contain itself within itself as spiritual as many times as it pleases (so that it could--and does, as we will see--have many different forms of consciousness in one and the same act of consciousness); but if it "reduplicates itself" in a quantitative way, and so also becomes a form of energy, it can has to contain itself as one form of energy, or one interconnected system--even though it still has all of the multiple "reduplications" of itself as spiritual (since they have no quantity).

So, as I said, the idea is that a greater act can do what is less, and what can "do itself" many times in one act can "do itself" in a lesser form while it is at it. There is nothing contradictory in this, even though it is what I said earlier is apt to be the mind-boggling aspect of sense consciousness.

The solution

It is possible for a spiritual act, in one of its "duplications" of itself, to "repeat" itself to a limited degree, and thus be both spiritual and energy.

Now of course, this is a theory of what sense-consciousness is, not an observed fact. But notice everything it explains. (a) It explains how sensation, as consciousness, can be aware of itself--because it is basically a spiritual act which contains itself within itself. (b) It explains how sensation is "connected" with the brain's nerve-energy output--because the nerve-energy is the "energy component" or the quantitative "reduplication" of the [one, identical] spiritual act. It isn't just "connected" with the nerve-energy; it is that energy. (c) It explains how an act of consciousness can react to outside energy--because the act is (because of this energy-"reduplication") a form of energy, which can react to outside energy. (d) It explains why consciousness does not "turn on" until the threshold of perception is reached--because it would be difficult to survive if we had to be conscious of all the energy impinging on it; so the conscious act remains only energy until a certain intensity is achieved, in which case it acts as its full self. (e) It explains why when the threshold of perception is reached, no energy is "drained off" to produce the conscious act--because the conscious act, as spiritual, does not have a quantity, and as the same as the energy, does not "take" any energy from it. (f) It explains why the conscious vividness increases as the intensity of the energy it is reacting to increases.

Actually, this last point needs a little expansion. The "degree of vividness" as conscious is actually a form of consciousness which represents a degree. That is, the way a bright light appears to you and the way a dim light appears to you are actually two different kinds of appearance, not really different degrees of the same kind of appearance. We think of them as degrees because they represent or refer to different degrees of the energy we are reacting to.

The evidence for this is that it is possible to hold the "degree of vividness" constant (so that a certain amount of energy is coming into the sense organ), and vary the form of the energy, asking the person to rate the various forms of his perception in terms of numbers. Thus, for instance, colors of a certain degree of reflectance and saturation and so on could be shown subjects, with only the hue (the color itself) varying. The subject could then be asked to say how much "more of a color" the blue card is from the green or the yellow, and so on, and he would be able to rank the different colors as "quantities" of "color." Now the colors are clearly perceived as different qualities, not quantities; and this indicates that, as far as the perception itself is concerned, what the "quality" is and what the "quantity" is are arbitrary.

This theory, then, says that the conscious act, which is also the form of the nerve-energy in the brain, has a conscious form which corresponds to the degree of the nerve-energy and represents the degree of the energy that stimulated the nerve to react. This is possible only if the nerve-energy and the conscious act are in fact one and the same act.

Hence, the theory, by making the one simple assumption that a conscious act can "reduplicate" itself once as a form of energy (and so be a spiritual act and a form of energy at once), explains much that is puzzling--and otherwise inexplicable--about sensation as consciousness.

THEOLOGICAL NOTE

Jesus is supposed by Christian Theology to be both God and a human being. Now a human being is a body (bundles of energy) organized by a soul, which is (at least as one "component") a form of energy. We will see more about the human soul later. For our purposes here, "to be human" means "to be limited" in a certain way, and also to a certain degree. but "to be God" means "to be absolutely without limitation."

This sounds like a contradiction in terms--and to the devout Jew or Muslim, it is. For them, to say that Jesus is God is blasphemy, because it assumes that a finite being can be the Infinite Being--which, for them, is absurd.

But what we have just seen about sensation makes the "incarnation" (the "becoming flesh," or "becoming a body") of God not unthinkable.

God, as spiritual, "does himself" over more than once in one and the same act. We saw this in the note on the Trinity. It is possible for one of these "reduplications" to "empty itself," as St. Paul says (Philippians 2) and "take the form of a slave" without losing the Divinity.

Jesus would then have two "natures": the Divine nature as the Infinite Act, and the human nature as the human being. The human nature would not be an "illusion," but a real nature, just as the energy-component of sensation is real energy. But by the same analogy, Jesus would not be two interconnected beings or two "people"--one Divine and one human--because these "two" are just "reduplications" of one and the same act; just as the act of sense consciousness and the nerve-energy are not two acts, but the same act.

Thus, Jesus, according to Catholic Theology, is one "person" (the Divine one) with two "natures." He really is God and he really is human; but he has only one reality--and that one reality is basically the Divine one. In the same way, the act of sensation is really a spiritual act, and its energy-component is an "aspect" of it, but a real one.

Notice, by the way, that Jesus' consciousness would involve sensation, which is reactive consciousness. God, as a pure spirit, could not be conscious in this way (since this kind of consciousness needs a quantitative "reduplication"); and so God began to see--in the literal sense--when Jesus was born. This is not to say that God's consciousness was incomplete beforehand; reactive consciousness is a defective form of consciousness.

So Jesus would have two types of consciousness in him: the Divine consciousness, always the same, absolute, undifferentiated Truth, and sensations and their derived concepts and in general the human consciousness, which involves reacting, comparing reactions, and learning new concepts. Jesus, as human, had to learn new concepts; as Divine, he had always the mystical awareness of the truth of what he knew.

Assuming that our theory of immaterial consciousness is true, then, let us briefly describe this consciousness and its faculty as it appears in us (and in animals, especially the higher ones).

DEFINITION: The sense faculty is the whole nervous system, with the brain as its central "processor." Consciousness, however, occurs only with the acts of the nerves in the brain itself.

So the faculty of sensation is extremely complex; it is so constructed that it receives different sorts of information from different kinds of energy from within and outside the body; it sends all this information to the central processing area, the brain, where it is integrated and filed away for future reference, and where it is connected with behavioral responses to the information.

I want to stress here, however, that this is one faculty. Following Aristotle, Scholastic philosophers in general have supposed that there are many interconnected "faculties" of sensation, on the grounds that a faculty (as a power to do something) is defined by its act, which in turn is defined by its object; and so if the objects reacted to are different, this would imply that the reactions (the acts responding to them) are different, which in turn implies different faculties.

I think, however, that the ancient notion of "immaterial" as "only half-way to spiritual" got in the way of a clear look at sensation. With our notion that the immaterial is spiritual-with-an-added-energy-component, it is easier to see that the act of sensation is one act, but an act which "reduplicates itself" as many forms of activity, corresponding to the various forms of energy it is reacting to in a unified way.

DEFINITION: An act is a polymorphous act if one and the same act is simultaneously many different forms of activity.

Sensation, then, and human consciousness in general, including thinking, is a polymorphous activity. As spiritual, there is no contradiction in the act's having many forms; as it "reduplicates" itself, its "reduplications" take on different forms; but it remains only one act.

The energy-dimensions or energy-components of these different forms of activity, however, are a system of interconnected forms of energy: the energy in the brain.

This theory of sensation, then, predicts that each distinguishable energy-output in the brain will have its own form of consciousness, and this form of consciousness will be one "dimension" or "component" of the polymorphous act of consciousness.

So it isn't really the case, if this is true, that sensation "reduplicates" itself only once as a form of energy; one and the same act does have a number of quantities, but each one is associated with a different nerve (or perhaps nerve-complex).

That is, energy-dimension of the act of sensation is an organized system of energies going on in the brain at the same time; but the conscious aspects of sense-perception all "interpenetrate" each other, so that each is, as it were, an aspect of the others.

It is easier to illustrate this than to describe it abstractly. As you read this page, you see certain colors; but are these colors seen as "aspects" of a pattern of shapes--or are the shapes "aspects" of the colors? The shaped colors are seen as at a certain distance from your eyes, they are seen as familiar or unfamiliar, and recall other shapes and colors (as well as thoughts as to what the shapes mean), and evoke certain emotions, tending to cause you to behave in various ways in response to what you are seeing.

All this occurs at once, in one single, simple act ("simple" in that it has no parts interconnected). But each of these "aspects" contains the others as "aspects" of itself, and is made different by and, if you will, affected by these other aspects--as, for instance, the familiarity you have with the words you see affects the way you see them; your expectation "makes" you see differently from the way you would if you were reading a foreign language. Thus, the different forms of consciousness are contained within each other, or interpenetrate each other; the act of consciousness is not a system of interconnected acts, but one polymorphous act.

Nevertheless, the energy-components of this polymorphous act cannot be like the act itself, because energy has a quantitative limit, and so can't "reduplicate" itself; any complex energy has to be a system of many interconnected acts; and that is what the brain's energy is. But remember, the brain's energy is not something that results in consciousness; it is the quantitative reduplication of the conscious act itself.

What, then, are the various ways in which the sense faculty reacts to "outside" energy? I put "outside" in quotes here, because this means energy coming into the faculty, but not necessarily energy from outside the body. Most of the energy we react to, of course, comes from outside the body; but we also react to energy within the body (hunger pains, the sense of balance, etc.).

These ways of reacting were traditionally called the "external senses," and treated as separate faculties. We will treat them as aspects of one faculty. Note that a detailed description of each of the aspects of the sense faculty really belongs to experimental psychology, not to philosophy. I will simply be giving a sketch here. Note 2: Think of these functions as various "inputs" into the information-processor which is the brain with its consciousness.

1. First, we react to objects or acts which are in contact with the nerve-receptor. This is called the "sense of touch."

There are actually many "senses" of touch, because there are different nerve-receptors (each with its own form of consciousness) which react to what is in contact with them. Under the "senses" of touch are included that of pressure, pain, heat, cold (there are different receptors for these and different forms of consciousness), balance (in the inner ear), the "muscular sense", the "kinesthetic sense" (by which we "feel" and movements of our bodies), and various others, such as itch and tickle.

The function for the organism (or "survival value") of the sense of touch is obvious. Contact with different forms of energy can be either beneficial or harmful to the organism; if it can distinguish which sort of energy is in contact with it, it can take steps to preserve itself.

Aristotle mentions that the simplest animals have only this sense of touch, and he may be right; though I would speculate that the second of the "senses" is probably also in every conscious body.

The point of this is that one way we can be in a position to get information from something is to be in direct contact with it. Touch is the "direct-contact" function.

2. Secondly, we react to the chemical breakdown of bodies taken into the organism; this is called the "sense of taste."

The actual taste of food we have is a combination of the act of the taste buds on the tongue (which react only to sweet, sour, bitter, and salty) and smell (which is in the interior part of the nose); the odor from the food goes up to the smell organ through the back of the mouth. But which organs are used for taste is really not philosophically relevant (though it is biologically); the point is that, as we destroy the objects we take into our systems, we react to this act of breaking them up--and we react favorably (a pleasant taste) or unfavorably (an unpleasant one) depending on the needs of the organism.

The function of taste, of course, is to let the organism know what bodies it takes into its system are compatible with it (good for it) and what are harmful to it.

Note that in human beings, the needs of the organism take a second place to our idea of what is "good," and to habits we have acquired. For instance, alcohol, which, as the excretion of bacteria, is a poison, tastes unpleasant at first, and the sensation of intoxication (= being poisoned) is distinctly disagreeable to the "uninitiated"; but our culture has decreed that the sensation of intoxication is to be called "pleasure," and so one defines it as such, and becomes all excited about it; and then one "acquires a taste" for the stuff.

Adults, in other words, and even children, can't use "tastes good" and "tastes bad" as criteria of "it's good for me" or not. This sort of thing works only in the animal kingdom, where instinct is the controlling act.

In any case, taste is the "substantial change" information receptor.

3. Thirdly, we react to the medium between us and an object at a distance. This is the "sense of smell." This sense is very highly developed in mammals other than humans. Actually, what activates the organ is small particles of the body in question, which break off and float in the air.

Here, what we smell (the "formal object") is the air itself as "polluted" by the particles in it. If your friend has just got through a workout in the gym, you don't really smell him or his sweat; you smell what he has done to the air. As hunting dogs show, you find the object causing the odor by sniffing around and following where the odor gets stronger.

Clearly, this "sense" has the function of letting the animal know what sorts of bodies are close enough to interact with the animal, and basically how close they are.

So smell is the "between" the body and the object detector.

4. Fourthly, we react to the actions of bodies as distant from us. This is the "sense of hearing."

With this sense, you hear by means of the vibration of the air molecules making the eardrum vibrate rhythmically; but you don't hear the sound as occurring either in your ear or in the air (as you smell an odor as in the air). In hearing, the medium between the organism and the object causing the sound is suppressed, and the sound is heard as at a distance from the organism and (because of binaural hearing) in a certain direction.

The function of this "sense" is that acts which make air vibrate are apt to be dangerous to the organism, and hence it is important to get an early warning, and especially a warning which will tell the organism which direction to run to escape the danger.

So hearing gives us "action-at-a-distance" type of information.

5. Finally, we react to bodies as at a distance from us. This is the "sense of sight."

Actually, what sight reacts to as such is color; and you could argue (as the Scholastic philosophers have) that shapes and patterns of color are not the object of sight as such but that of the "unifying sense," which integrates all of the "external senses" into a single perception. But I think this is a quibble, because there is really only one faculty of sensation anyhow; and so how you divide up the various "sub-faculties" is arbitrary. There seems to be pretty decent scientific evidence that patterns as well as colors are largely visual.

The point here, however, is that as far as the form of consciousness of the "sense" is concerned, when we see, we do not see the light-as-it-hits-our-eyes, nor even the light itself (you can't see light as such), nor the distant body as causing the air to "light up," the way hearing is conscious of the action of the distant body. What we see is the body itself; the body which is either radiating light or reradiating ("reflecting") light that is falling on it. We see the source of the light that strikes our eyes, and the whole rest of the causal chain by which it gets into our eyes is suppressed in consciousness; and so we see the body at a distance from us.

It is the suppression of all of the "media" from consciousness that makes us think of sight as the most objective of all the senses. But of course, our visual impression of any object is only a subjective reaction to it, and is not a "copy" of either the object itself, or of the light which it is sending out.

Sight, however, does make other objects present to us, and present as distant from us; and this can be extremely useful, especially in an animal that can think. This is probably why sight is more highly developed in humans, and less so in other animals (even high animals, like mammals).

So sight gives us information about "what is acting at a distance."

The reason there are only five senses is that these exhaust the possible ways information can get into any system: the object has to be either in contact, interacting with, or away from the instrument; and if it is away from the instrument, then the information has to be either the medium, the action on the medium, or the object which is acting on the medium. And those are the five inputs we have described.

If, in other words, someone had a "sixth sense," then it would have to belong to one of those categories. Let us suppose you had a receptor like some fish, that could perceive electrical fields. You would either perceive the field as permeating the surroundings (in which case it would be a "second smell," analogous to the different versions we have of touch), or you would perceive what the energy-source was doing to the atmosphere (which would be another type of hearing), or you would perceive the energy-source itself (in which case you have a second sight).

Such extra types of sensory inputs are possible, but I make no pronouncements about whether any person actually has them. The evidence is quite tenuous, and fraud is just as plausible an explanation in most cases.

But there is a general fact about sensation that must be stressed.

Note well

As far as sensation itself is concerned, the form of consciousness is always just a subjective reaction to the energy or the body outside the faculty (or the organism).

Different forms of energy will generally produce different reactions, and so the organism will be able to behave appropriately, even though the organism doesn't really (as Aristotle seems to have thought) "become" or "imitate" the act it is reacting to. We will see later how human beings can use the fact that our reactions are consistent to get around the subjectivity of the reaction and learn about the outside act that caused us to react.

6.4.2. The processing acts: the "internal senses"

All of this different information coming into the organism would cause havoc if there weren't some way to put order into it so that the organism could behave appropriately in relation to what was important, and ignore what was not, and could learn from the past and not have everything absolutely new all the time. This is the function of what the Scholastics call the four "internal senses."

6.4.2.1. The integrating function

The first of these internal functions deals with handling the information that is coming into the brain at any given time.

DEFINITION: The integrating function of sensation is the uniting of all the information coming into the brain at any one time into a patterned whole called a "perception."

This sub-faculty--or better, this organizing function of the brain--had the traditional name of "the common sense" (i.e. the "sense" that is "common to" seeing, hearing, etc. so that you see the body which you also hear). But this term is too easy to confuse with "common sense," meaning "ordinary understanding," (i.e. it's "common sense" not to go out into the cold lightly dressed); and so this term is not useful.

Following some Scholastic philosophers, I used to use the term "unifying sense," but this got confused with the "unifying energy" of the body (the soul), and so that term is not terribly much better. Hence, the term above, which describes what is happening and isn't confused with other things.

The energy-"dimension" of the integrating function, as an act of the brain, probably has a great deal to do with the brain waves. Brain waves are complex surges of energy through the whole brain, which doubtless are performing several functions--but it does seem that at least one of them is to integrate the information coming into the different areas into a single complex "information-signal."

But like all acts of the brain, this function has its own form of consciousness; and in this case, the form of consciousness of the function as such is the form of subjective space.

That is, the integrating function "adds" the "spatiality" to our perceptions, so that when we have a perception, we have an act of consciousness that consists, say, in the forms of various colors and shapes, the forms of various sounds, various tactile sensations, various odors, etc., each of which is "located" in the general pattern of a "volume" before our eyes.

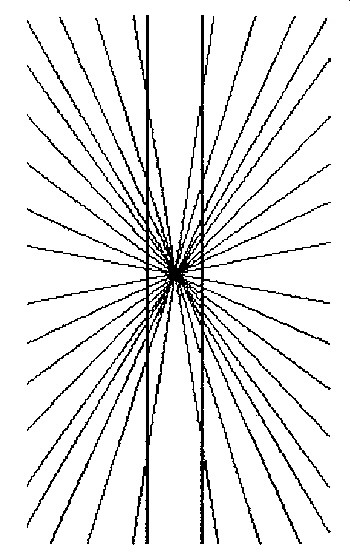

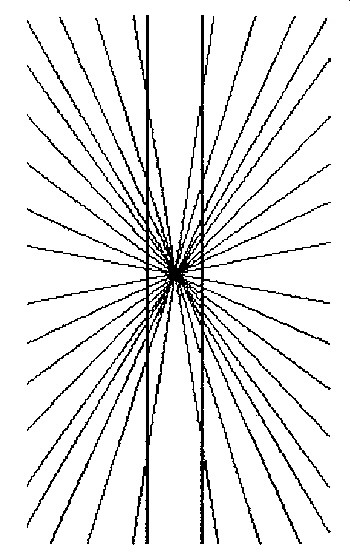

This "volume," by the way, is basically the "space" of Euclid's geometry, when tricks of perspective are taken into account (such as lines appearing to merge on "vanishing points" on the horizon). It is what causes optical illusions such as the one just abovet (the vertical lines are straight). Actual space (the dynamic relationship among the fields of objects) is, as Einstein has shown, not at all like "space-as-we-perceive-it." Real space has (from the point of view of perceived space) curved straight lines in the vicinity of massive objects, and so on.

The integrating function in human beings is to some extent under the control of thought: if we are expecting to see something (called "mental set" by the psychologists), we tend to "overlay" our perception with data from imagination (see below), and we can see more clearly than we actually see. For instance, if you see a person a long distance away, and someone tells you "That's John, isn't it?" your knowledge that it's John and your memory of what John looks like tends to affect the perception so that now you see the object as looking like John.

The second function we have corresponds more or less to what is called the "memory" of a computer, even though it has traditionally been called "imagination," with the term "memory" reserved for something more specialized, as we will see shortly.

DEFINITION: Imagination is the function of storing and recalling wholes or parts of past perceptions. It can combine parts of one with parts of another.

How we do this storing and recalling is quite mysterious, according to the psychologists who have studied it. We seem to have two "memories," analogous to the two "memories" of a computer; one is like the RAM of the computer itself, the temporary, working area, which gets erased when you turn the computer off; the other is like the disk or tape, on which things are stored to be accessed later.

We could go into the physiology of this, but it would take us deep into the area of experimental psychology and of biology, and it is much better to leave this to the scientists. The point here is that there are something like "pathways" of nerve-complexes, which, once stimulated, make it easier for energy to "travel through" this particular set of nerves, and at a lower level. Thus, once we have had a particular perception, we can reactivate it by energy from the brain-waves, without any new energy's being introduced from outside.

Presumably, a given nerve (associated with a given form of consciousness) can be used in any number of nerve-complexes; and so each nerve in a stored complex can act as a switch to take energy out of this complex into some other stored complex that also used this nerve. In this way, when a given set of nerves is reactivated, "pieces" of other stored perceptions can be "stuck onto" it. Thus, you can imagine a unicorn by recalling a horse, and imagining a horn (which you also recall) in the middle of its forehead.

The actual storing and recalling is called "imagination" and not "memory" partly because of this recombining aspect, and partly because the third "processing function" (as we will see shortly) is called "memory"; but it deals with dating these images.

Whatever the mechanism for this function, its form of consciousness is, of course, the image, which is the same as a perception, except for two things: (a) the image, as an act of consciousness, is aware of itself as not a reaction to outside energy, but as spontaneously produced; and (b) it is generally much less vivid than any perception (because perceptions involve energy added to the brain).

Imagination in humans can be consciously controlled, as when you deliberately try to imagine a blue unicorn. This is then called "creative imagination."

6.4.2.2.1. Hallucinations and dreams

Imagination is fairly easy to fool. Since images are usually much less vivid than perceptions, this difference in vividness is the clue we ordinarily use to tell whether we are fooling around with the data already stored in us or a receiving new information (perceiving). But we can have very vivid images or low-level perceptions, and can therefore become confused.

When an image is confused with a perception, we call this a "hallucination." This is not the same as an "illusion" (like the one just above). An illusion is a misleading structuring of the information coming into your brain; a hallucination is a mistaking of an image for a perception. With an illusion, you are seeing what is there, but you misinterpret it; with a hallucination you seem to be seeing (or hearing, or whatever) something, but there's nothing there.

Generally, this happens when we are expecting to perceive something that is dim enough as to be at the limits of perceivability. If you are trying to hear a faint sound, such as a distant bell, then your expectation of hearing it can make you think you hear it even though the bell has not rung. If someone says, "Do you smell smoke?" you may start sniffing and not be able to tell whether you really smell it or whether you're imagining you do.

Psychedelic chemicals send bursts of energy into the brain, stimulating nerves there more or less at random, and very vividly. This does two things: first of all, it creates a hallucination, because we have an experience that was not caused by energy coming in through the senses, and so is basically of the "imaginary" variety--but it is so vivid as to be like a "super-perception."

Secondly, however, the experience is apt to be so vivid as to be "burned into" the nerve-paths, so that a restimulation of part of this experience later can cause a new rush of energy into the nerve-set and reawaken the hallucination in almost all of its vividness.

Thus, on a "drug-trip" you may see a morning glory blossom grow to be larger than you are and swallow you in its embrace--and the experience may be as vivid as if it is actually happening. Then, weeks later, you might be walking down the street and see a morning glory--and all of a sudden it grows huge and swallows you again.

The taker of psychedelic chemicals is apt to find it difficult to distinguish the imaginary from the real; and we call that sort of difficulty "psychosis."

Moral: psychedelic chemicals are marvelous things to stay away from.

The reverse process of hallucination, that of thinking that a perception is an image, is probably the explanation of the fairly common experience called the déjà vu (French for "already seen").

In this experience, we "could swear this has all happened before"; it's as if we remember it, even though we know it couldn't actually have happened in the past. What seems to be happening is that, for some reason, our perceptions (perhaps because of trying to pay attention to too much at once) drop down to a level of vividness very close to that of vivid images. If they drop low enough, we seem to be experiencing and recalling the same thing at the same time, since the experience has the level of an image, but we know intellectually that we are perceiving.

Dreams are a kind of non-hallucinatory hallucination. That is, in a dream, consciousness itself is at a low enough level that the "awareness of the awareness" is not operating very much, and whether the experience is imaginary or is actually happening is not something that the person concerns himself with.

What seems to be happening in dreams is this: The "RAM-type memory" of the brain (the working area) tends to get filled up with a day or so's information, and the "switches" in this area need to be "reset to zero" so that they can receive new data. Sleep does this. If a person is deprived of sleep for two or three days, the information coming in will be overlaid with what is already there, and there will be a mess of perception/images, or hallucinations.

Now then, certain experiences during the day get passed over or ignored, and the energy in them tends to be stuck at a rather high level. The "resetting" function of sleep finds this energy too high to allow it to "zero-out" the nerves, and so it stimulates this nerve and lets it "run" for a while, draining out the energy (as the energy goes from this nerve-complex through others) until the level falls low enough to be able to set the nerves back to zero.

Of course, as the energy flows out of this nerve-complex, it follows the path of least resistance, which would be the path that either has been most vividly experienced originally, or most often used; and so the sequence of images in a dream depends on which experience is most vividly associated with the one that the energy happens to be in at the moment, and has nothing to do with what we would call "logic."

The traditional name for this third processing function, as I said above, is "memory," even though it doesn't really deal with storing and recalling past experiences. What it involves is the "pastness" of the past and the "presentness" of the present.

DEFINITION: Sense memory is the function of classifying perceptions or images in order of vividness, with the perception (the most vivid) being taken as "now."

So with sense memory, you don't actually do any recalling of the past (imagination does that); but when an image is recalled, it's "place" in your internal filing-system is "felt," so that you recognize it as more or less remote from the present.

Note that sense-memory is not actually the understanding of when some past experience occurred; though understanding the "date" of an event you experienced generally relies heavily on this function. When you date something in understanding, you say things like, "I know it was last Tuesday, because I was eating a hamburger, and we have hamburgers on Tuesday." Sense memory in itself is just a "feeling" of greater or lesser remoteness from the perception of the moment.

This "sense" is also quite easily fooled. Apparently, stored perceptions tend to "dim out" at a fairly regular rate; but (a) experiences which were originally very vivid are apt to be classified with ordinary ones that happened later, and we remember them "as if it were yesterday"; and (b) experiences that are often repeated tend to lose their "dating" and become a kind of "timeless" image. Your recollection that 2 + 2 = 4 has no "time of experience" connected with it.

The form of consciousness added by this function is that of subjective time.

This is "time-as-its-passage-is-felt," not our experience of clocks. Thus, when we are concentrating heavily on something (as in an examination), the "clock time" seems to go very fast, because we are not paying attention to the flow of our impressions; and when we are sitting idly in the doctor's waiting room, the clock's time seems to go very slow, because we are noticing each tiny event as it passes.

Psychedelic drugs like marijuana distort this sense, because they create a "super-present" by the charge of energy that surges into the brain. The sense memory doesn't know what to do with this experience, and so sometimes a "trip" seems to take no time at all, and sometimes it seems eternal.

The final organizing function of sensation has as its energy-"dimension" the basic "program" by which the brain operates, taking information coming into the brain, assessing it in connection with the brain's monitoring of the state of the organism, and directing energy through complex routes into the motor nerves--and in this way causing behavior that responds to the information.

Let me mention at the outset that "instinct" in the sense I am using it is not the same as what psychologists mean by the term. For a psychologist, an instinct is a completely genetically fixed behavior pattern, not something that is modified by learning. Thus, the dance the bee does when coming back to the hive is an "instinct" in this psychological sense, because the bee will do the dance even if there aren't other bees around to see it. For a psychologist, a "drive" is a modifiable behavior pattern: a tendency to do something. Again, I have no quarrel with their terminology, which suits their purposes. But we have different purposes here, and therefore, here is what I mean by the terms:

DEFINITION: Instinct is the function by which the body responds appropriately to the information it is receiving.

You might think of it this way. The basic operating system is what instinct in our sense of the term is. This would be like the basic operating system (Windows, MacOS, or for you old computer buffs, DOS, say) of your computer. But instinct has several major programs called drives, like the sex drive, the hunger drive, the fear drive, and so on, which are like the computer's word processor, database, and spreadsheet programs, which are what actually do the job. Instinct itself (a) monitors the state the body is in, (b) checks the information being received (or imagined), and (c) has a set of basic rules as to which drive to start operating. It then sends energy into the drive-program, which produces more complicated processing of the information to get appropriate results.

The form of consciousness added to our experience from instinct is emotion.

Instinct does two main things in the conscious body.

First, it directs attention, so that only part of the available information gets above the threshold of consciousness.

It seems to do this by "picking out" the aspect of the information that is "important" based on the monitoring of the body's state at the moment, and directing energy from the "unimportant" areas to this "important" one, so that the "important" one is perceived more vividly and the other information is not noticed.

Thus, when the blood sugar level drops below a certain point, the hunger drive begins to operate, and food becomes "important." You start feeling hungry, imagining (recalling) the refrigerator and what is in it, and you find it difficult to keep your mind on philosophy. The hungrier you get, the more difficult it is to think of anything except eating.

Notice that this function can be controlled deliberately, to some extent. When we consciously control attention, we call this concentration. Animals cannot concentrate, because instinct is the controlling activity; their attention is directed by instinct itself, and they have no way to direct instinct.

Secondly, as we said, instinct directs information by complex routes from perception to behavior.

I am not going to go into the various drives we have, because this is a matter for psychologists, not philosophers.

Each of these basic drives is modified (at least in higher animals) by what happened in past times when that "program" operated. Thus, a dog which snaps at the bone you give him and gets a slap on the cheek has the "grab it!" program modified so that after a few times, he takes the bone gently from your hand. He learns to expect food only at a certain time of day; he learns not to choke himself on his leash or not to run after cars, and so on. Extremely complex behavior can be induced in animals by taking the basic drives (which seek gratification or to avoid harm) and manipulating rewards and punishments.

This, of course, also happens to some extent in humans; but human drives are different from those of all other animals in significant ways, because we can consciously control how the energy is to go in our brains.

First, when we deliberately direct the energy in our brain, we call this "doing logic" or "reasoning." The animals' instinct is its "reasoning"--and it can be a "reasoning" of a very complicated sort, as I just mentioned. But it is not consciously directed, as true reasoning is. When a human being reasons, he knows not only that the next step is the next one to take, but why it is the next step.

Second, animals' drives work out for the survival of the animal or its species. As the controlling function in the animal, this would have to be the case, or the animals would die off. So what "feels good" for an animal is in the long run what "is good" for that animal (or that type of animal)--as long as its instinct hasn't been tampered with, as when animals are trained to smoke.

But humans' drives are not this way. Each drive seeks its own gratification, and just becomes stronger the more it is acted on; and in general, the drive will operate to the detriment of the human organism unless it is regulated by thinking and reasoning.

That is, the human being has to form an objective evaluation of what is in fact for his benefit, and regulate his behavior based on this understanding, not on instinct or his emotions, or the emotions will destroy him. Take hunger. If you eat whenever you feel hungry and eat what happens to taste pleasant, you will find yourself fat and malnourished to boot. You must find out how much your body needs and what foods form a balanced diet and base your eating habits on this objective information, not on what "feels right."

Note well

For human beings, the "way you feel" is no indication of what you "really are"; what "feels right" is no indication that it really is right.

Notice that since emotions (as the conscious dimension of instinct) are automatic responses to the information coming into the brain, there is nothing right or wrong about feeling emotions. The emotions are not your "true self" expressing itself; and so if someone you can't stand comes into the room and you feel a surge of murderous hatred, you don't have to reproach yourself for feeling this, or try to pretend you don't really feel this way.

This does not mean that you should behave toward this person as if you hate him. He is a person and as such deserves respect, and expressions of human brotherhood. Because of this, when you act in a friendly manner to him, even though you feel hatred for him, you are not being a "hypocrite"; you are acting consistently with the real relation you have to him; it is the feeling of hatred that is the "hypocrite" in this case, because your instinct is reacting inappropriately with the real situation.

But the point is that, if you act consistently with the real situation (and not as your emotions prompt), you don't have to be ashamed of having these inappropriate emotions. They are not in themselves either good or bad; they just happen. In fact, if you ignore them and act appropriately with the reality of the situation, then the emotions will become less strong as time goes by, and eventually will tend to become the ones that are consistent with the real situation.

You have then "trained yourself." You have used yourself as understanding the real situation to train yourself as an animal. And if you get yourself perfectly trained, then your emotions will fall into line.

But the point is that if you follow your emotions, you will be training yourself into inappropriate behavior patterns, which will only cause you trouble later.

And at this point, when the drives become strong enough so that the mind and thought cannot control them and we act as we choose not to act, then emotional unhealth occurs, and you need the help of a psychologist.

And since this is the place where philosophy and clinical psychology overlap, let us leave the subject here, and let the psychologists concern themselves with the various ways we can get out of control, and the various means there are to help us get back into control of ourselves. The point here is that psychological problems are basically problems with the way the instinct has been modified either by organic malfunctions of the brain or by repeated behavior.

HISTORICAL SKETCH

Plato (400 B.C.) held, as I have said, that sensation was a material kind of consciousness, because it involved the individual and the changing.

Aristotle (350 B.C.) said that sensation was the taking on of the act of the sensed object without its matter, and so there was a certain spirituality to it in his theory. He was the one who classified the "five senses" (though he recognized that touch was multiple) and the four "internal senses." He thought that the heart was the basic integrating organ (doing what we say the brain does), because when he cut up bodies, he was not able to see the nerves, but noticed all the blood vessels, which led to the heart. It is from this that we think of the heart as "where feelings occur." He thought that the action on the sense organs produced modifications like chemical changes in the blood, which were then integrated in the heart. Much of his analysis of sensation was quite brilliant, and is still valid today--though much of it is also colored by the lack of information at the time.

St. Thomas Aquinas (1250) stressed the "immateriality" of sensation, as quasi-spiritual, but with the conditions of matter (space and time). For St. Thomas, perception had a conscious form, but imagination, since the object was not present, had to "produce" an image as a kind of internal "object." This, I think, is a mistake. The image is nothing but the form of the act of imagining, and is an "object" only because the act is aware of itself. St. Thomas did not think that a sense-act was aware of itself; it needed a "second act" (that of the integrating function).

Both Aristotle and St. Thomas, in addition to the "senses" named, talked about "sense appetite," (emotion) as something distinct from instinct, on the grounds that instinct was a reaction to the object and the "appetite" was a "tendency toward" it; and different objects imply different faculties. I think this is a too-mechanical reading of what is going on in sense consciousness. I think also that our experience with computers has shed a lot of light on instinct--light which these great thinkers did not have to guide them.

Once the Renaissance and Descartes (1600) were reached, sensation as immaterial was lost sight of. Either, with Descartes, it was a purely mechanical process and thinking was the only spiritual one, or with the British Empiricists Locke (1670) and Hume (1750), it was all there was, and its immateriality was of no concern: they were interested in it only insofar as it revealed or did not reveal the real world "outside" us.

Hence, an analysis of sensation has been left, by and large, to modern science, which unfortunately, is infected with "measurementitis." Important discoveries have been made, but often a great deal of time is wasted with elaborate experiments that come to trivial conclusions, because trivial conclusions are all that can be "measured."

Sigmund Freud (1900) escaped this tyranny and did significant work on instinct. But not having a very solid scientific nor philosophical base to work from, but only the experience of people with emotional problems, many of his conclusions, though brilliant, were erroneous. Much of his work is valid, however, and even a lot of the invalid things are suggestive toward the truth. His theory of dreams, for instance, is, I think, faulty as "wish-fulfillment," but it has led investigators toward a better understanding of what dreams do for us.

B. F. Skinner who was alive in the middle of the twentieth century, was the most prominent "behavioral" psychologist. Unfortunately, he was over-enamored of measurement, and much too eager to argue from what happens when you train pigeons to what human behavior is. As an "objective scientist" he refused to get into "introspection," and our awareness of our own consciousness; and the result is that he considered things like "freedom" and "control over instinct" and so on illusions of those who think human beings have a "special dignity" that other animals don't have. I have no problem with people not using certain types of evidence (such as introspection); but when they say that this evidence doesn't exist and then start drawing conclusions that contradict it, I don't think much of them, I am afraid, as scientists.

Our consciousness reacts to the outside world, and it can only do that if it is not a purely spiritual act, but is immaterial.

Sensation has to be energy, because spiritual acts can't change, and sensations change; sensations depend on the nerve-energy in the brain and will not occur unless certain nerves are active, and sensations vary in vividness depending on the quantity of the stimulus-energy. But sensation is consciousness, and so, as we saw in the last chapter, can't be energy.

The solution to the dilemma is that a spiritual act "does itself" many times in one act, and there is nothing to prevent one of these "repetitions" of itself to be at a lower level, having a quantity. Thus, a spiritual act can simultaneously be a form of energy, even though what is basically just energy cannot add anything to itself. What is greater can do less, though what is less cannot do what is greater.

An immaterial act is one which is basically spiritual and so reduplicates itself, but which reduplicates itself once with a quantity, and so is both spiritual and energy.

Thus, the energy in the brain, when it is above a certain level (the threshold of perception) is not just energy, but the energy-dimension of the immaterial act of sensation. Each nerve-energy-output has its own form of consciousness associated with it, all of which become aspects or dimensions of the one polymorphous (many-formed) act of sensation a person is having at a given time. Thus, the brain is the faculty of sensation, which turns sensation on and off, and which directs which sensation occurs when.

The sense-faculty has five sorts of "input": acts in contact with the organ (touch, in its various forms), acts involving destruction of what is taken into the body (taste), acts reacting to the medium (air, water) between the body and a distant object (smell), acts reacting to the activity of a distant object (hearing), and acts reacting to the distant object which is acting (seeing).

These various inputs are organized in the brain in four basic ways: first, they are integrated into a single perception, adding the subjective form of space (integrating function); second, these perceptions are stored, and they or parts of them can be recalled by energy in the brain (imagination); third, the stored perceptions are classified by date received (memory), adding the subjective form of time, and finally are related to the state the body is in, directing behavior by a complicated program (instinct), adding the form of emotion. Any one of these in human beings can be consciously controlled to a greater or lesser extent. In animals, instinct is the controlling function.

Exercises and questions for discussion

1. If sensation is both consciousness and a form of energy, doesn't this prove that a form of energy can be conscious, and so refute what we said in the last chapter (that energy can't be conscious)?

2. Since "spiritual" means "without quantity" and "material" means "having quantity," then isn't "immaterial" a contradiction in terms? It means "spiritual and having quantity."

3. Some fish can perceive electrical fields. Does this mean they have a sixth sense, or is this one of the five?

4. In what way does your imagination help you to see?

5. Does the fact that the instinct can apparently get out of control and produce compulsive behavior indicate that human beings are not simply complex animals? Why or why not?