Truth and Goodness

[These topics are treated in Modes of the Finite, Part 1, Section 5.]

I mentioned in the historical sketch at the end of the preceding chapter that modern philosophy has been concerned with whether we can know about what is "out there" outside our minds. This is called the "epistemological problem," because epistemology is the study of knowledge in its relation to objects.

A detailed examination of the problem can be very complex, and is beyond our scope here. If you want to see more about the approach I think is the correct one, I have a whole book on the subject, called Knowledge: its Acquisition and Expression. This chapter is going to be a summary of most of that book.

The epistemological problem

If our sensations are (a) subjective reactions to the objects and acts that produced them in us, and (b) are not like the objects or acts that caused them, then how can we ever get any knowledge about the objects themselves?

The solution I propose to the problem (which in some ways is quite new) not only explains how we can know about things as they are "out there" independently of our reactions to them, it also explains why we understand relationships among our sensations. In other words, understanding and reasoning (that is, thinking), is the way we "bypass" the subjectivity of our sensations and understand facts about the world as it is.

The approach to this chapter, then, is to set up the problem in its most stark way, to show how understanding solves it; and then to define what facts are, and what their relation to the judgment (the act of understanding) is; then to define truth and error, truth and lying, and truth and falseness; and finally, to define goodness and badness as a different way of looking at the truth-relation.

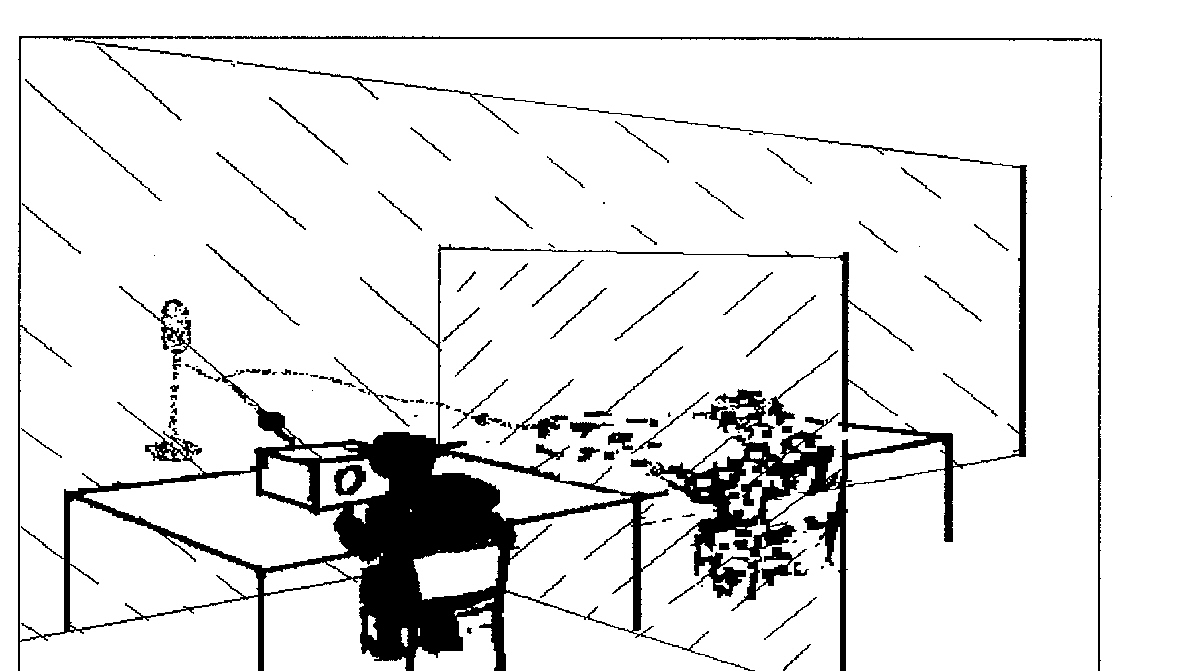

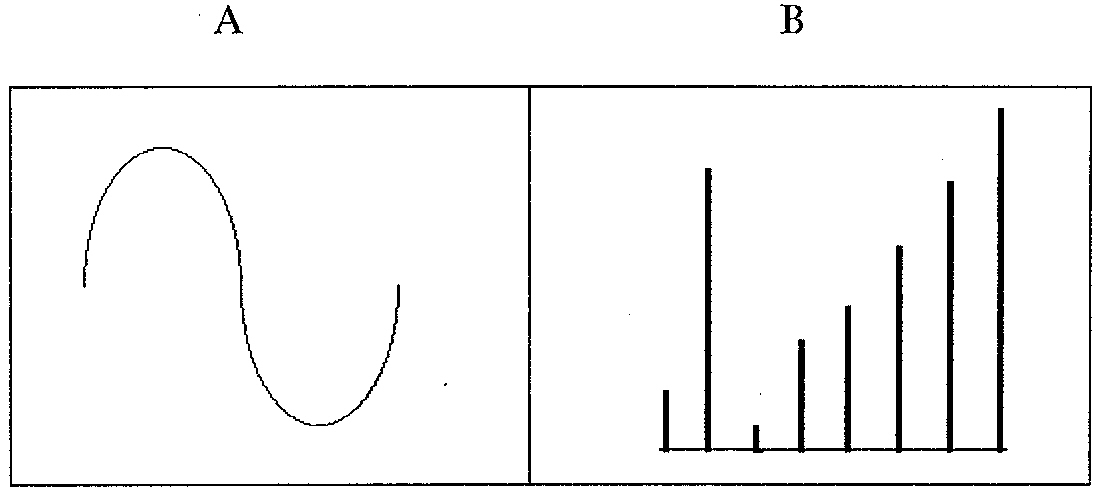

To begin, let us consider the following sketch:

It shows two people in booths in a room. Each person has an instrument which is connected through the back wall to something they cannot see (but which we know is a microphone). Each instrument is different from the other one. Person A has an oscilloscope, and Person B has a set of tubes up which mercury can rise. Neither can see the other's instrument, because of the low wall which separates them, but they can hear each other. We assume that neither has ever seen either what is behind the back wall, or the other person's instrument.

This is a model of our minds. My mind is (presumably) a receiving instrument from energy outside me. I can't perceive what the energy "out there" is except by using my instrument (i.e. I can't leave the room and get behind the wall that separates me from the microphone).

So the first problem will be whether I can know even that anything is going on behind the wall (whether I can know that there is anything outside my consciousness) or whether my instrument (my mind) is doing everything by itself.

Secondly, I can't get into your mind (go over to your booth) and get a look at what is happening in your perceptions (what your instrument's output is like), and so I can't verify that the way things look to me is the same as the way things look to you.

Here, I am making a worst-case assumption. I am assuming that your perceptions and mine are different, so that when you see grass, the way it appears to you is not the way grass appears to me; that is, if I were to have your form of consciousness, it would be something like what (to you) would be the sound of e-flat.

The object

Can this model show how both observers can agree on aspects of what is going on behind the wall (indicating that we can know aspects of what is outside us)?

That is, I want to show, using this model, is that the two people, just by using their instruments, will be able (a) to know that there is indeed something behind the wall, and (b) to agree on what is going on behind the wall. This in spite of the fact that neither of them can ever get behind the wall and that the reading of one instrument is even a different type of reading from the reading of the other.

If they can do this, and if our minds are analogous to instruments reacting to some in-itself-hidden source, then we might not be able to know what the source is, but we still might be able to know things about it. That is the gist of the argument.

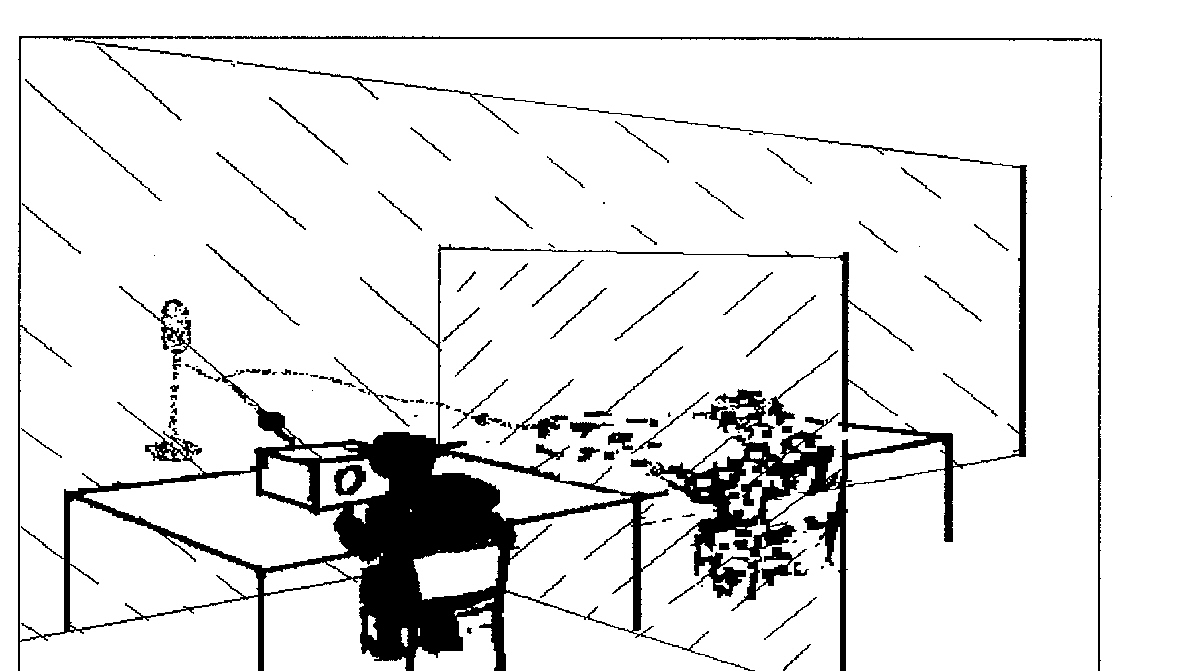

It turns out that the problem is solvable. Let us say that we play a tuning-fork into the microphone. Since the two observers have different instruments, their screens, perhaps, will look like this:

Can either of them convey any information to the other that the other can agree on?

Yes. Suppose A says, "Hey! Something happened!" B will answer, "You're right."

What does this mean? Let us assume that both A and B can spontaneously make patterns on their instruments. But in this case, A knows that he didn't produce the pattern, and B also knows that he didn't produce his pattern.

This corresponds to a recognition of the difference between perceiving and imagining. Since the acts of perceiving and imagining are conscious, then (as I said two chapters ago) when we are imagining, we are aware that we ourselves are making the image; whereas when we are perceiving, we are aware that our minds are "receiving" something and not fooling around with energy that is already there.

Conclusion 1

Even if our sensations are utterly different from the energy that caused them, we can still know that there is some external something by being able to distinguish perceiving from imagining. And even if our subjective impressions differ from person to person, this will still be true for everyone.

That is, since our conscious acts recognize whether they are spontaneous or reactions to something-or-other outside us, then we are like the people above; when there is something "out there" sending a message, we can agree at least that it is not a figment of our imagination.

At this point, the people can't say anything at all about what it is that produced the patterns (remember, they can't tell that there's a microphone back there). All they know is that something happened.

But let us now play a flute into the microphone. The two patterns now look like this:

Can A tell B anything more than "Something happened"?

Yes. He can now say, "Something different happened," and again B will answer, "You're right."

That is, even though A's pattern is not like B's, and even though A's pattern (and B's, for that matter) is nothing at all like the sound that caused it; still, a different sound produces a different pattern in each case, and each of the people recognize that this is so.

Does this transfer over into the case of our subjective impressions? It does.

Conclusion 2

Even if our sensations are not like their causes and not like anyone else's, it is still true that, given consistent faculties, different energies will produce different sensations.

Finally, let us replay the tuning fork. The patterns again become:

Can either of them convey any information to the other that the other can agree on?

A can now tell B, "The same thing happened as happened the first time," and B once again says, "You're right."

And as time goes on, by each of them comparing the patterns he is getting to patterns he received in the past, each can begin to classify the "somethings-going-on" behind the wall, so that each can recognize a given type of "behind-wall activity" as "the kind that happened the first, third, seventh, and twelfth times."

Conclusion 3

Similar forms of energy falling on the same sense organ will cause the sensations to be similar to each other; and this is true even if the sensations are not like the energy, and not like those of any other person. All people with consistent faculties will agree that there is a similarity in the causes.

In other words, what each person objectively knows about what is going on behind the wall is the relationships among the causes of the read-outs of their instruments.

Do you see now how understanding is going to enter into this? Understanding is precisely the knowledge of the relations between sensations (and, as we can now see, therefore the relations between the objects that caused the sensations).

General conclusion

Understanding gives us objective knowledge, because it reveals to us the relations between objects--and these relations are the same as the relations between the sensations.

So the function of understanding in human knowledge is to enable the person to circumvent the subjectivity of his subjective reactions to the world outside him, and to know at least something about the way the world actually is.

Since human knowledge comes about by way of being acted on by outside energy, and since effects are not copies of their causes, then it is impossible for a human being directly to know the thing that is causing his reaction.

But this does not mean that he cannot indirectly know about it. And this is what understanding, which knows relations, enables him to do.

Thus, when we are acted on by the light that emanates from grass, we have a reaction to that light that is not a "copy" of the light itself. But when we are acted on by the light that emanates from an emerald, we again have a reaction that is not like the light itself--but that is like the reaction we got when we were acted on by grass.

So when we understand that the grass is like an emerald (in the way it can affect eyes), and form the concept "green," what we mean by "green" is not "the reaction I have to grass" ("green-as-I-see-it"), but "whatever it is that grass ('out there') has in common with an emerald."

And this is why you and I, even if your reaction to grass is different from mine, can agree on what "green" is, and can call the same things "green." That is, when we see a frog, we both say that it is green, and when we see a toad, we both say that it isn't; and when we see a grasshopper, we both say that it is green, and when we see a locust, we both say that it isn't. Why? Because the same form of energy is going to cause the same reaction in you every time (other things being equal); and it will also cause the same reaction in me every time. Hence, since "green" refers to the cause of the reaction (i.e. what is "out there") and not the reaction itself (what is "in here" in our minds), then we both mean exactly the same thing by "green" even if our reactions (the way green appears to each) are different.

The cause of these samenesses and differences in our reactions has to be, basically, outside our sense faculty, or there is no way to explain why the reactions are not always the same. What I mean is this: as you look at this page with the same eyes at the same time, the letters look different from the background. But your eyes and mind can't explain why you get these different reactions, because it's the same eyes and the same mind; the difference must be due to the fact that what they're reacting to is different.

DEFINITION: An object of knowledge is any thing or act that can cause a reaction in a knower.

DEFINITION: objective knowledge for a human being is knowing relationships among objects he (directly or indirectly) reacts to.

DEFINITION: A fact is a relationship among objects.

Note well

A fact is not a thing or object. it is a relationship among objects. A fact is not a statement, even a "proven statement." it is a relation among objects. Facts exist whether we know them or not. Our knowledge and statements depend on the facts, not vice versa.

Statements are expressions in language of what we think the facts are; or in other words, they are expressions of our judgments about the facts. But they are not facts. Even if you prove a statement, the statement remains the expression of your judgment about the fact and is not the fact, any more than your knowledge creates the facts it is aware of. The facts are "out there" waiting to be known; they do not depend on our knowledge.

In any case, what we know objectively is facts about objects, not the objects-as-they-are-in-themselves. And the reason is that our knowledge is based on the fact that our sense faculties are immaterial acts that can be affected by outside energy, and so we cannot directly get at the energy itself.

Note that objective knowledge does not have to be this way. A pure spirit--God, for instance--cannot be affected by anything outside himself, and consequently cannot form concepts as we know them. God knows "objects" by being their creator, not by being affected by them; it is because he causes them to exist that he knows them.

Thus, for instance, God has no "concept" of me (i.e. that I am like you in humanity, for instance). God knows me as I know the book I am writing; I know it even before the words appear on the page; it is the idea I have of the book that causes the book to exist, not the book that causes my idea of it. And since every finite act I perform (i.e. every property I have and everything about me) is impossible unless God causes it to be this way, then God knows absolutely everything about me--but not in a conceptual way. He knows it in a way totally foreign to our conceptual way of thinking.

St. Thomas speculates that pure spirits, who cannot know by being affected by things, have "infused" knowledge. That is, any knowledge they have is given to them by God as he creates their minds; and consequently, any knowledge they have of objects other than themselves is not due to being affected by them, but to God's giving them this knowledge as a form of their consciousness.

Presumably, this is my way of knowing you, reader, if you are one of the people who is reading this after I am dead. You can't affect me; but I can affect you; and I care about you and want you to be helped toward your goals by what I do. And so I know you--but this knowledge of you is given me by God, and is not due to any ability you have to change me directly. Your prayers for me (and I hope there are some) are, so to speak, retroactive, and make a difference to the way I was when I still could change, and so to me as I now am in eternity.

For those of you reading this while I am still alive, don't laugh just yet. We haven't got to the theory of what choice means to the person, and what goals in life have to do with what happens after death. When we get there, we will see that life simply doesn't make sense unless our non-self-contradictory ambitions are fulfilled after death. I happen to have huge ambitions, that is all.

But the point is that objective knowledge and conceptual knowledge (understanding) are only synonymous for the human being while he is still a living body, and are not necessarily synonymous with objective knowledge as such.

Be that as it may, our knowledge as we now exist is conceptual; and therefore all that we can now understand about any object is facts about it: relations it has with other objects and/or relations it has within itself. The theory I am developing says that our judgment about an object (our understanding that it is related in a certain way) will be parallel to the fact (the relation it actually has).

If only it were that simple.

The trouble is that there is usually not just a single cause-effect action-reaction between the object and our minds. Usually, objects cause sensations by means of a complex chain of causes; and some of the causing agents in this chain are, as I mentioned in talking about sensation, our own expectations and past experience. When we expect to see John, we "recognize" him from a long way off, even before the object is close enough to be distinguished; and this "recognition" consists of an overlay on the perception by the image of John stored in our imagination. And this is one way that the reaction may not be what it should be. The person comes closer, and we see that it was really Frank, not John.

Put on sunglasses, and everything seems a different color than it was; look at clothes under fluorescent light and under incandescent light and under daylight, and the same cloth will look different colors.

And so on. There are any number of ways in which a cause can be introduced into the causal chain without our realizing it, making the judgment of what the fact is different from what the fact really is. That is, we look at the red cloth under fluorescent light and form the judgment that it is the same color as the flower of the fuchsia plant; but in fact it isn't.

DEFINITION: A mistake or error occurs when the judgment of what the fact is does not agree with what the fact is.

That is, a mistake is a misunderstanding. You understand the objects to be related in a certain way, and the objects are related in a different way.

DEFINITION: Truth occurs when the judgment of what the fact is agrees with what the fact actually is. The judgment is then said to be "true."

That is, if you think that grass is green (i.e. like emeralds and frogs), your idea of its color is true. If you think (for whatever reason) that it's blue (i.e. like the ocean and sky), your idea is mistaken.

Note that facts are neither true nor false; they are just facts. It is the judgments about them that are true or mistaken.

This is the primary meaning of the word "truth." It has several, which we will have to explore a little.

Note well

For truth to occur, the judgment must be brought into conformity to the fact.

That is, it is the business of the knower to see to it that his judgment agrees with what the fact is, and not the other way round. This is another way of saying that facts are facts, and your thinking that they aren't the way they are doesn't change them. We have to find out what the facts are; we can't "make up" facts by using our imaginations. When Shakespeare imagined Caliban, this didn't make Caliban exist; in fact, there is no such person. Even the actor who plays Caliban isn't really Caliban; he's just an actor. We don't create facts; we discover them.

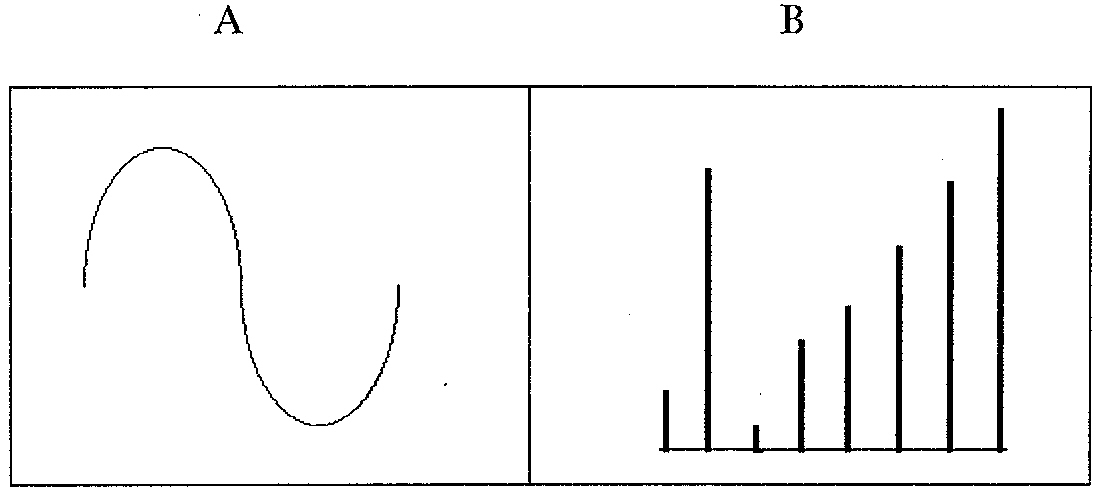

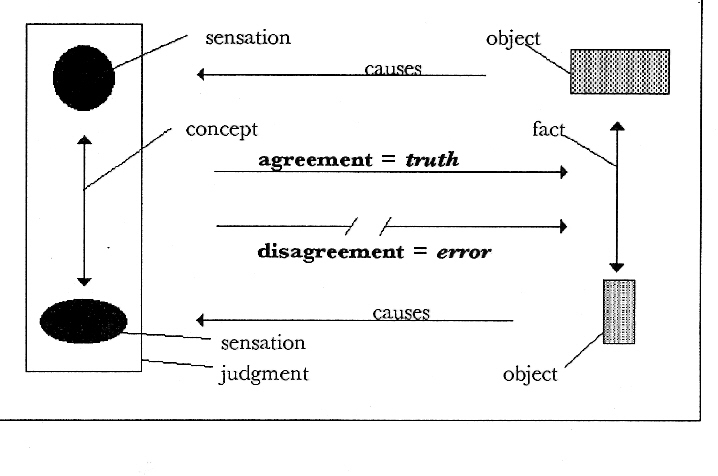

Here is a diagram of the truth/error relation. The objects cause sensations (which are not like them); but the concept matches the fact in the truth-judgment, and doesn't in the error-judgment.

THE TRUTH/ERROR RELATION

Granted, we can change things, and alter objects so that new facts about them come into existence; but we do this by acting on them, not just by thinking; and if we don't act in the proper way, then our goals are not achieved.

I am stressing this because of the "disease of the present age" I mentioned in the first chapter: the mode of thinking that facts are what we make them in our minds. It is because the solution I proposed here has not been recognized that we got ourselves into the diseased situation I spoke of.

At this point, it would be a good idea to reread Chapter 1, Section 1.2. and its subsections.

But I also want to call attention to the fact that our judgments must conform to the facts because looking at the truth-error relation from the point of view of the facts' having to conform to the judgment is actually the goodness/badness relation (evaluation), not the truth/error relation (understanding), as we will see.

A further complication arises when we take language into account. We not only form judgments about objects, but we express those judgments in words, as I said in the preceding chapter. What about the relation of the statement to the judgment and to the fact?

Most words, of course, are words in an existing language; and it is "decided" by the culture what relationship the word is to stand for. This is the only way people can communicate, practically speaking. If, like Humpty Dumpty in Through the Looking Glass, words "mean what I want them to mean, neither more nor less," (as he used "glory" to mean "a good knock-down argument"), then we can't expect people to know what we are saying.

Now it is quite possible for a person to have a perfectly true judgment, but to express it in language that says the opposite of what he thinks it says. Suppose a person thinks that the "hoi polloi" are the upper class of society (the word means the "many" or the "masses" or the "low class"). He then says, "Queen Elizabeth is one of the hoi polloi." She is a member of the upper class; and this is what he meant to say; and so his judgment is true. But his statement is not, because it says that she is a member of the lower class, when she isn't.

DEFINITION: Falseness is a term that belongs to statements (in language). Falseness occurs when the statement does not match the fact.

That is, the statement is false when it doesn't express what the fact is.

DEFINITION: Truth occurs in a statement when the statement states as a fact what actually is a fact.

Note 1

Judgments are true or mistaken; statements are true or false.

Note 2

The statement's truth or falseness is in itself independent of whether the judgment is true or mistaken.

Why is this? It is really a convention of terminology, but there's a reason for it. When you are listening to someone, he is telling you what he thinks the facts are (his judgment of the fact). But what you are interested in, most of the time, is not what is going on in his mind, but what he is reporting about reality. That is, you are using him as evidence for the facts he knows.

Hence, the general purpose of factual communication is to inform someone else of facts we happen to be aware of. Therefore, the statements are taken to be statements-of-fact rather than statements-of-what-I-think-the-fact-is. Hence, we are interested in whether the statements actually express the facts or not.

And the fact is that statements, of course, can be both false and, in a sense, mistaken. For instance, the one above about Queen Elizabeth is false because it is the result of a mistake about what the word means. But there are two ways that a statement can be mistakenly false: (a) by expressing a mistaken judgment (accurately); or (b) by expressing a judgment inaccurately--so that the statement does not agree with the fact.

Oddly enough, if the judgment is mistaken and the person mistakes how to express it, it can happen by accident sometimes that the statement is true. Suppose a person thinks that "spiritual" means "high-powered energy" and that thinking involves a great deal of energy. He then says "Thinking is a spiritual act." What he says is true; but what he meant to say is that thinking is a form of energy--which is false.

The point here, as I said, is that the truth or falseness of the statement does not depend on what the speaker's judgment is, but on what the fact is. The statement is true if it agrees with the fact, and false if it doesn't--irrespective of the speaker's idea of what the fact is.

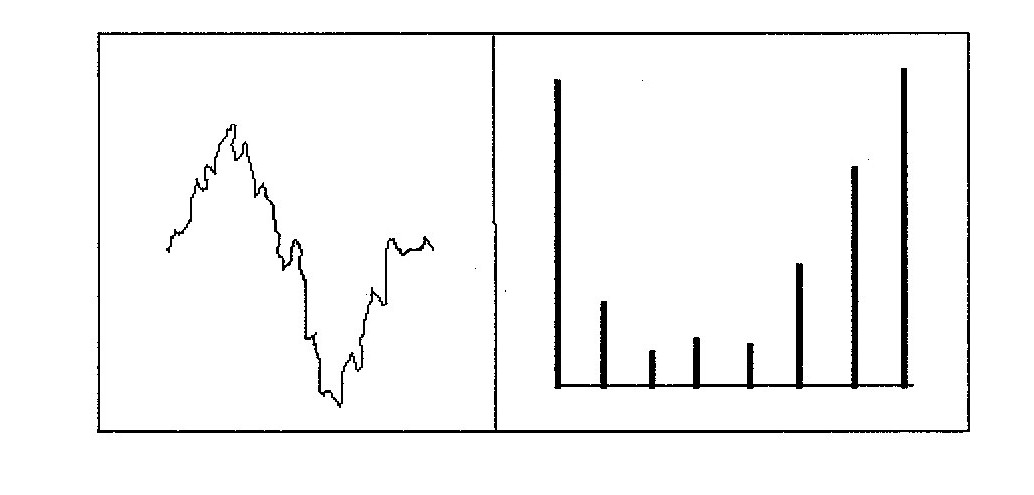

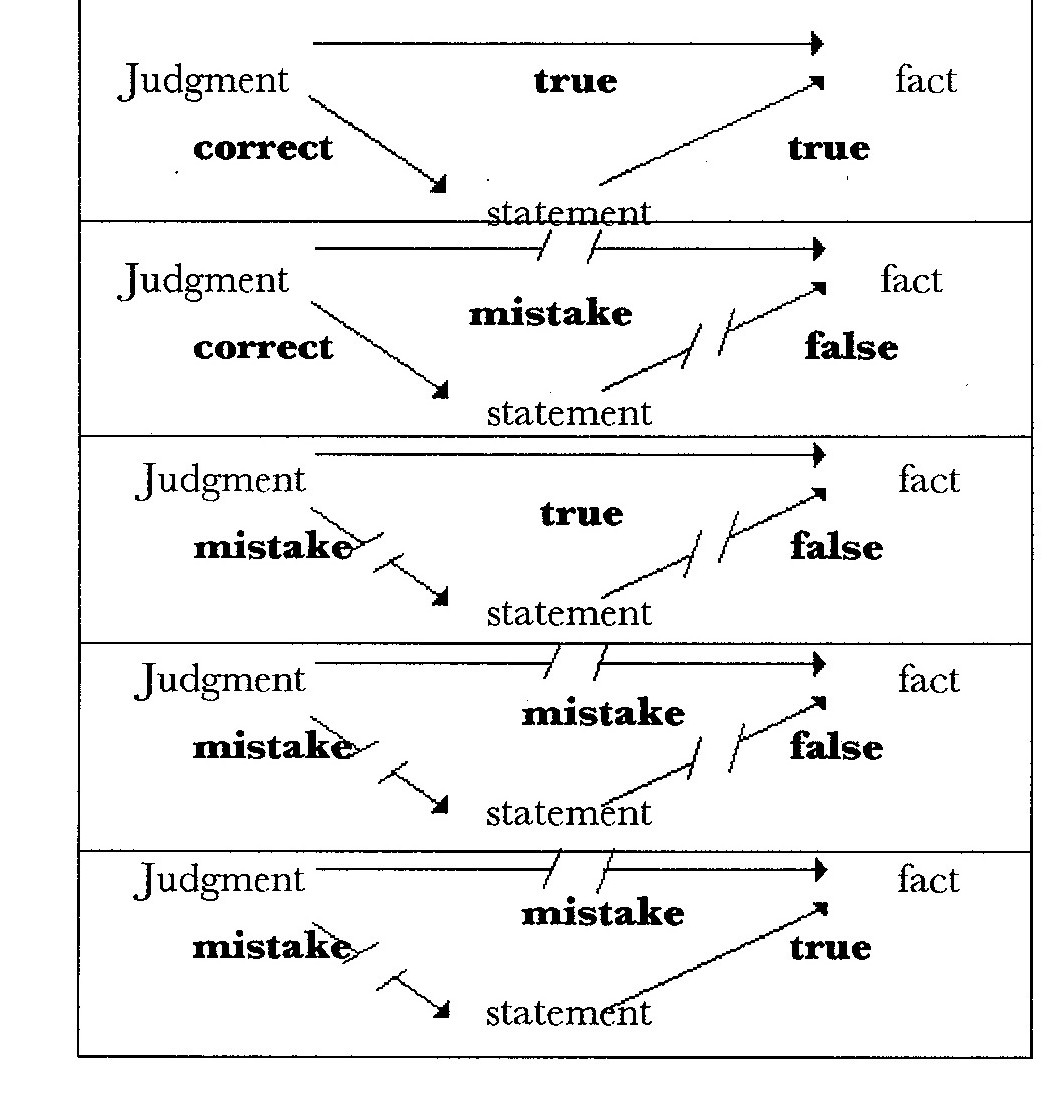

The relationship, then, between the truth or error of a judgment and the truth or falseness of a statement is quite complex, if all the possibilities are taken into account. You can see them in the diagram below. Note that there are three possibilities involved when the mistake is in how to express the judgment, the last of which is the case above, where the statement turns out by accident to be true, because the mistaken statement happens to cancel out the mistaken judgment. Most of the time, of course, if there is a mistaken judgment and a misstatement of it, the result will still be false.

STATEMENTS, JUDGMENTS, AND FACTS

There is still another complication that we must at least mention. A person may knowingly and deliberately try to misstate what he thinks the facts are. In this case, his statement has a moral dimension, whatever its actual relation to the facts.

DEFINITION: A lie is a deliberate attempt to state as a fact something that the speaker thinks is not a fact.

If the speaker's judgment is mistaken, then the lie can be simultaneously a lie and a true statement. That is, if you think that John has left the room and you want Sally to think that he's hidden in the room, and you say, "John's still here, hiding behind the sofa," your statement is a lie.

If, unknown to you, John pretended to leave the room and hid behind the sofa, your lie is (by accident) a true statement, because John in fact still is in the room, hiding behind the sofa.

So the lie, unlike the false statement, does depend on what the speaker's judgment is. It has to disagree with his judgment, and disagree not because of a mistake, but because he chooses to make it disagree.

The point here is that when a person makes a false statement, to answer him with "That's a lie!" is very often a false statement. His false statement could be the result of (a) a mistaken judgment about the fact, (b) a mistake in what the language he expressed his judgment meant, or (c) a lie--or (d) your mistake in understanding either the fact or what he said. It's actually rather difficult to prove that a person actually lied.

Getting back, now, to the judgment and the fact, there is still another relation we have to consider--or rather, another way of looking at the relation we have considered.

I stressed that, in the truth-relation, we had to make our judgment agree with what the fact is. Someone might, however, wonder, "But why do I have to do that? Why can't I try to change the facts so that they agree with the way I think they are?"

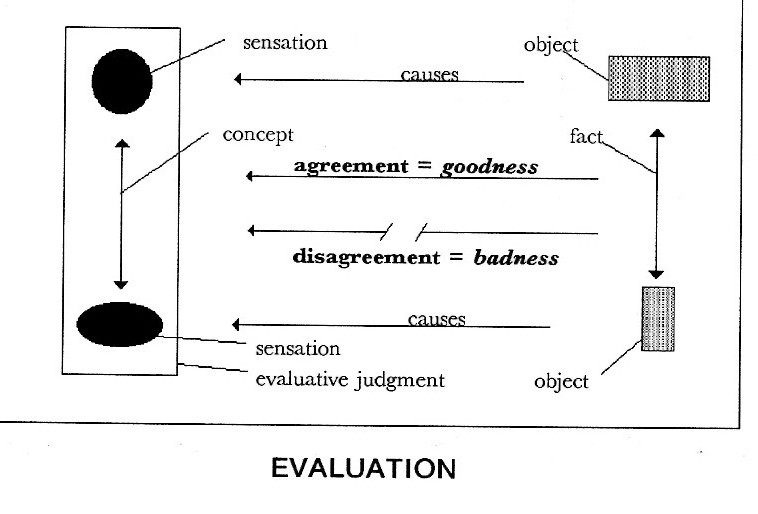

There's no reason why you can't; but when you do this, we don't call this "understanding," but "evaluating," as I said; and the relationship is no longer one of truth and error but goodness and badness.

What is behind it is this. (1) we have experiences that are reactions to reality, but we also have imaginary experiences that we construct out of pieces of past experiences. (2) Using these, we can create imaginary states of affairs. (3) We can then use these imaginary situations as a kind of standard that we want the facts to conform to.

8.5.1. The evaluative judgment

The result, of course, is that the relation of the facts to the judgment is the same relation, but looked at backwards. Now the facts are supposed to conform with this construct we have made in our minds.

DEFINITION: An ideal is an imaginary construct used as a standard that the facts are expected to conform to.

DEFINITION: An evaluation is a judgment of whether or not the facts agree with the ideal.

That is, it is one thing to imagine yourself to be a tiger; this is just an act of imagining. But when you imagine yourself as having a job you like, a home, and a family, you compare what you are now with this imagined state of affairs, and want or at least would like--in some way expect--the real world to be this way.

What you are doing here is, instead of taking the fact as the "independent variable" and adjusting your judgment to agree with it, you are now taking the ideal (the mental construct) as the "standard" and expecting (or hoping) the facts live up to it.

In the case of imagining yourself to be a tiger, you simply say, "Yes, but I'm really not a tiger," and there's no problem. In the case of imagining yourself with the job you like, you say, "Yes, but I don't actually have that job," and you think, "But I ought to have it."

Or, you imagine a world without nuclear weapons, where people don't go in fear of having the whole world blown up around them. "Why couldn't things be this way?" you say. The imagined state of affairs is now the way things ought to be; you are "judging" the facts in relation to your expectation of the way things "really should be," as if your judgment expresses the "really true" state of affairs, and the facts are in a sense false.

This is evaluation. It is clear that the judgment ("the world is free of nuclear weapons and the terror they bring") is false. But instead of saying, "Sorry; my mistake; there are nuclear weapons," you don't give up the ideal; you use it to say that there is "something wrong" with the facts.

Note well

Whenever we say "ought" or "should," we are making evaluative judgments, not factual ones.

There is, however, a second step in this process. You can create ideals and evaluate facts, and complain if the facts don't live up to your ideals; or you can then make a choice and say, "Well, I'll change things and see to it that the facts get to be the way I conceive them."

Note well

Choices use ideals as ways of making the body unstable and getting it into a process whose purpose is the realization of the ideal. The ideal then becomes a goal.

That is, you imagine yourself as having a college degree, and you complain about not having one. Then you say, "I'll go to college and get one," meaning that you will now bring the facts into conformity with your ideal. This is a choice (as we will see later); and the ideal has changed somewhat. It is no longer simply a standard for judging the facts (and complaining or being happy); it has now become a "future fact": it is a goal. It is now what you intend by your choice.

DEFINITION: Goals are imagined states of affairs that one intends shall be facts.

Goals are ideals; but not all ideals are goals. Some ideals are just nice to think about, but we have no intention of putting them into practice; we just complain if they're not the case. So, you might have as an ideal being a millionaire; it would be nice to be one, but you aren't going to take the steps necessary to be one. If someone gave you a million dollars, you'd take it, but you're not going to set your sights on achieving it. It's an ideal, but not a goal.

In essence, the difference between a mere ideal and a goal is that when an ideal is a goal, there is an instability set up in the person, so that he acts in the direction of the goal as his purpose (which of course is why it is called a "goal"). With an ideal, there is no instability set up, and no change takes place; it only involves evaluative judgments.

Note well

To the extent that you merely evaluate without changing the ideal into a goal, all you are doing is exercising your imagination so that you can complain that the world doesn't agree with your imaginary construct of it. Sterile evaluation is a waste of time.

Now then, when we compare the way the world is with these ideals, and notice that it does not agree with our ideals, we say that this is "bad." When it does agree, we say that this is "good."

DEFINITION: An object is bad when some fact about it does not agree with our ideal of the way the object "ought" to be.

DEFINITION: An object is good when the facts about it agree with our ideal about the way the object "ought" to be.

As you can see by comparing this with the truth/error diagram above, the relation here is simply the reverse of truth and error. In the truth/error relation, the fact is the "independent variable," and the judgment has to "tune itself in" and become the same relation; here, the judgment is the "independent variable," and it is assumed that the facts about the object have to "tune in" to our concept of what they should be.

That is, in general, when we consider objects as "bad," we think that they should be changed, to come into conformity with our idea of them; when we think of them as "good," then we have no project for them; we are satisfied.

The point, of course, in goodness and badness is that these concepts depend on ideals we construct. We did not get this ideal from anything "out there." How could we? It doesn't exist. So we made it up. This implies a couple of important things:

Conclusion 4

Goodness is not an objective aspect of anything.

The only objectivity goodness and badness has is the fact that the object conforms (or does not conform) to the person's preconceived idea of it. But the preconceived idea has nothing objective about it, even if it was formed from piecing together many actual experiences. The point of the goodness/badness relation is that the standard is subjective, not objective.

Therefore, one person's idea of what is "good" for some object may be very different from another person's idea of that object as "good"; and because of the first point just made, there is no way of deciding which of the two is right.

Neither person is objectively right, because the ideal is a mental construct, not a fact, and so is subjective, not objective.

Note also that God does not think in terms of goodness and badness. God has no ideals. This is the exact opposite of the way we tend to think God thinks. But since God's ideas cause things to exist, then if God had any ideal for me (i.e. if God thought of the "real true George Blair" as a completely virtuous person), then that ideal would be what existed. No, God's idea of me is exactly this miserable excuse for humanity which I am; and of course it follows from this that God is not and cannot be "dissatisfied" with the way I am.

THEOLOGICAL NOTE

Then this implies that God doesn't care whether I sin or not. This is perfectly true. God can't be affected by me in any case; as James says; "in him there is no change nor shadow of turning," and so nothing I do can make him any happier or disappoint him in any way at all. Even if I am damned, God is perfectly satisfied with me, and I have fulfilled his will for me--which is to be the self that I have chosen to be.

Then why is it said, "This is his will, your salvation." This means (a) not that God is "angered" by our sins with the result that he won't forgive us unless we placate him (for him there is nothing to forgive); but (b) that salvation is offered to each of us, and is ours should we choose to accept it--but if we don't, then this does not thwart God's "will," because there is nothing we can do that he doesn't help us do.

He redeemed us, not because it saddened him to see us damning ourselves, but because (since we are embodied and able to change) it is not a contradiction for us to change heart and repent, though it needs a miracle for us actually to do it, and he can supply that miracle--not that it gives him any kick to do so. It is done purely and simply for us, not for any "affection" he has for us. And an act that is done absolutely purely for the recipient, and in which the agent has no personal stake whatever, is an act of absolute love.

So goodness and badness is purely on our parts, not on God's.

There is, however, a kind of "badness" (moral wrongness) that has some objective basis behind it. An object which acts in contradiction with its nature has performed objectively a morally wrong act.

DEFINITION: An act is morally wrong if it is inconsistent with the person performing the act.

For instance, a lie, as I said above, is a deliberate attempt to communicate as a fact what you think is not a fact; it directly contradicts what factual communication is all about. Such an act is morally wrong, and inconsistent with any "factual communicator."

We generally think of these things as "bad," because we expect people to act consistently with what they are; it is the rare person who thinks of dishonesty or hypocrisy (pretending by your actions to be what you aren't) as agreeing with his ideal of the way people "ought" to act.

Thus, moral wrongness is almost universally regarded as bad, and when people disagree on whether a given act is "really bad" or not, they are disagreeing, really, on the objective fact of whether it is consistent or inconsistent with the person acting. (E.g. "Are abortions bad?" is another way of saying "Are abortions morally wrong?" If they are morally wrong, the person would expect people not to do them.)

Note, however, that although moral wrongness is regarded as bad, moral wrongness and badness are not the same thing. Moral rightness and wrongness are objective facts (consistency or inconsistency); moral goodness and badness depend on subjective expectations.

This opens up the whole area of morality, which is an extensive study in itself; so let this be enough for our purposes here.

Note that the reason that goodness/badness is subjective and truth/error is objective is that facts are facts, and it is the facts that are "out there," and our knowledge which depends on them. Facts do not depend on our ideas of them; hence, while ideals and goals have a basis that is subjective, not objective, truth and error have an objective basis.

Ideas get "translated" into facts when they become goals and we choose to act to change the facts so that they will agree with our goals--as when a student actually enrolls in a college, with the goal of actually having a degree. Unless he acts, however, the facts remain what they are, and his "goals" are not goals, but simple abstract ideals.

But this leads us into what choice entails, which is the subject of the next chapter.

HISTORICAL SKETCH

Plato (400 B.C.) thought that truth consisted in our mind's being in contact with the "Aspects," which were the spiritual realities we know with our spiritual minds. Error, for him, came when we clouded our knowledge with sensations (which were our contact with the imperfect "sharers" of the Aspects).

Aristotle (350 B.C.) had the theory of abstraction; and since for him sensation was a kind of "becoming" of the object in a non-material way, then when we abstracted the "nature," we got at the truth of things.

Following Aristotle, St. Thomas Aquinas (1250) held the basic "conformity" theory of truth we enunciated above: the judgment is to conform to the facts. Both Aristotle and St. Thomas, however, thought that goodness was something objective, which was what attracted the "will" (the spiritual faculty of choice). Hence, things were "really" good or bad; goodness or badness did not depend on how you considered things. Thus, there would be an objective goodness, which God would know and "desire" in some analogous sense; and this led to all kinds of Theological conundrums about God's "permissive will" "allowing" bad things which he didn't "really want" to happen but "couldn't prevent" because a "greater good" would come from them. (E.g. it is supposedly "objectively better" to be free and have some of us damned forever than for us not to be free--though it's hard to see how you would find evidence to support this, since animals aren't free and are doing all right).

With Descartes (1600) the whole truth-question got turned inside out. Descartes started with what he thought was an undeniable fact: "I think, therefore I am," and argued from the "badness" of his doubting to the "fact" that he had an idea of a perfect being--which he couldn't have got from himself (since everything about him was imperfect), and therefore must have got by having a perfect being give it to him: hence there is a God, who won't deceive us. So "truth" had God as its guarantor.

This whole thing is actually full of flaws (we can get the idea of "perfect" by negating things that we think "bad," without having it infused into us); and in fact people began disputing it right away.

For the Rationalists (Descartes, Spinoza--1650--and Leibniz--1680), there were "innate ideas" that we always had in our minds, and were not arrived at by abstraction from sensations; and truth was something like Plato's notion, of not letting sensations cloud the mental grasp of the ideas themselves.

The Empiricists (Locke--1670--and Hume--1750), held that there were no innate ideas, and in fact no ideas in our sense at all. All there were were sensations, simple or complex; and the complex ones were what we mistakenly thought of as "abstract ideas." Since we didn't know whether there was anything "out there" or not (or whether we really had "minds" or not), then truth was simply the consistency among the ideas themselves.

For Immanuel Kant (1790), objective knowledge consisted in imposing order on the haphazard data of sensations, thus making "objects" out of blocks of data (for him, actually, the "object" is what I called the "perception"); reason, which created ideals, was naturally deceptive, because it made us think that these ideals (concepts of God, freedom, spirituality, and immortality) actually existed, when they couldn't. There was no question of a conformity to what was "out there," because there was, for Kant, no possibility of knowing anything at all about the "X" out there. All knowledge is "phenomenology": the study of the appearances.

Georg Hegel (1820) carried phenomenology to its ultimate extreme. The Truth was the Absolute--absolutely everything--and could be known by a dialectical process, where we follow the steps The Absolute takes in "becoming aware of itself in its own otherness," which it produces out of its own mind. Every concept is true, and every concept which is not yet the sum of all concepts is false. Every incomplete concept is implicitly Absolute Truth; and Absolute Knowledge contains absolutely all truth--and we have it, because we are the Absolute in his "otherness," and when we know Him, He knows Himself in us. For Hegel, "the real is rational and the rational is real." What Hegel did not realize is that the real is both rational and non-rational (though not irrational--but there are gratuitous elements in it), and the rational (consciousness) is both real and not real (real and imaginary).

In the United States, the Pragmatists William James (1900) and John Dewey (1920) held that truth is "what works"; which basically was again a kind of consistency among our experiences. If they contradicted each other, then obviously this was false. Actually, these people made a "definition" of truth out of a pretty decent criterion for deciding whether a judgment is true or not; but the two are not actually the same.

There are many, many other names who have dealt with objectivity and truth since Descartes; but the whole history of the epistemological problem has been based, I think, on a fundamental misconception: Up to the present, "truth" has been pretty much equated with "reality." It has been held that what is is true, and what is true is. I think that this is only in a sense true, and in that sense it is misleading. It supposes that what our objective knowledge is is knowledge of objects (which sounds on the face of it obvious--though I think it's false); and therefore, "conformity" theories are various versions of a kind of "copy theory" of different degrees of sophistication; or the "object" is taken to be inside the mind (the appearance itself), and truth is some kind of consistency in the object.

The various difficulties in "consistency" theories have lately led people like Kurt Gadamer to say that you never really can know what another person means; so any interpretation that is internally consistent is as good as any other (though he seems to be annoyed when other people interpret him in a consistent way which is different from what he thought he was trying to say).

Further still from reality are the "deconstructionists" like Jacques Derrida, who hold that there really isn't any "one meaning" to anything; what statements say is not the person's idea of what the facts are; they are attempts to "modify behavior" in other people. Hence, they express where the person is "coming from" or his "agenda" rather than "facts." But of course, if applied to Derrida's own writings, they themselves don't then express the real way we communicate, but are just his attempt to make a name for himself by saying outrageous things. Clearly, he must have intended to be disbelieved, because if you take him seriously, you can't take him seriously, because his own writings about deconstruction have to be deconstructed.

And all because Descartes couldn't see how the subjective impression could report anything about the reality outside us.

The theory I propose is that the object (the energy or bundle of energies which acts on our senses) is what we know about with our objective knowledge; but it is not what we know with our objective knowledge; what we know objectively are facts about it. But facts themselves are not "things" or "realities"; they are relations. That is, the similarity of all red objects is not an actual interconnecting of all these objects, as if it were a string or field that attached them all together.

No, the fact is itself not something real; but it is the way we get at knowledge about the reality, because of the indirection necessary due to our being affected by the reality. Similarly, truth is not itself a reality, but a fact about reality's relation to our knowledge of it.

I think that the tortured history of philosophy from 1600 to the present shows that unless this view is taken, all sorts of really silly theories are the only result you have any reason to expect. Some of the theories--like Hegel's--are exceedingly profound and complex; but if you take a wrong premise ("truth is reality") and use it as an explanation, and then try to make it fit the facts, you are bound to come up with a really complex and difficult theory.

The problem of objective knowledge is that our only contact with the world outside us is sensations, and these are subjective reactions to energy, and are not like the energy they react to. How then can we know things as they really are?

The answer is that if our reacting mechanisms (our sense organs) are consistent, then a given energy will produce a given reaction; and by understanding what the relations are among the reactions, we can know that the same relation occurs among the energies that produced these reactions. But this is what understanding does; therefore understanding is the way we reach objective knowledge.

What we understand is not objects, but facts: relationships between objects. Our understanding (our judgment) is true when we understand as a fact what the fact actually is (when the objects are related in the way we understand them to be). If the objects are related in a different way, the judgment is mistaken or in error.

We then express the judgment in a statement; the statement is true if it states as a fact what the fact actually is, and is false if it does not. There is a complex relation between the statement, the judgment, and the fact, so that a false statement does not necessarily mean a mistaken judgment. Truth and falseness in the statement ignores whether the judgment is mistaken or not.

A lie is a deliberate misstatement; a statement that is intended to be the opposite of the judgment. But since the statement is true or false depending on whether it matches the fact, not the judgment, a lie can be a true statement also (if the judgment is mistaken).

Goodness and badness look on the relation between the fact and the judgment in the reverse direction. The judgment is taken to be the standard, and is thus an ideal for evaluating the facts. When the facts about some object agree with the judgment, the object is called "good"; when they disagree, it is called "bad," or "there is something wrong with it." (Moral wrongness is not badness; it is acting inconsistently with what you are, and is a fact.) Since the ideal is constructed by the person, then there is no objective basis for goodness and badness, as there is (the fact) for truth and error.

Exercises and questions for discussion

1. Since I can never know how grass looks to you, then it follows that I can't say that you're wrong when you say that grass is purple, because that's the way it looks to you. Then how is it we say that colorblind people don't see things correctly? Who are we to impose our "style of seeing" on them?

2. Relationships (e.g. the "connection" of all red objects because each is red) don't really exist as such. Then how can we say that it is the relationships which are what we objectively know? The objects are the (related) bodies, not the relationships. But we only have contact with them by our subjective reactions. So we don't really know anything objective after all.

3. If truth means that the judgment is the same as the fact, then isn't what you think is true only true for you, because someone else can have a different judgment about what the facts are? So truth is really subjective, not objective.

4. If our knowledge of what facts are is based on a relationship between sensations, then how can we know a fact that we have never seen or directly experienced? For instance, how can you know that it's a fact that you lost consciousness last night, if you can't experience your own unconsciousness?

5. If we rank goals in terms of importance (by figuring out which we would give up if we had to give up one to get another), and if this process is subjective, doesn't this mean that nothing is objectively important?