Note that properties are not parts. The hardness of a piece of wood, its size,

shape, color, are in fact behaviors of the wood in response to energy around it; its parts are the atoms that make it up.

Note that properties are not parts. The hardness of a piece of wood, its size,

shape, color, are in fact behaviors of the wood in response to energy around it; its parts are the atoms that make it up. Bodies

If, as we said in Chapter 1, we are going to talk about embodied life, or living bodies, then we have to know what a body is first, before we go on to the distinctive characteristics of a body as living.

The study of what a body is and what characteristics it has as such is extremely complex, and could easily take several volumes to do justice to. Here we can do no more than skim briefly over a vast area of philosophy, and instead of presenting evidence and discussing contrary positions, we will just give the conclusions that seem most reasonable, based on the examinations that have gone on through the centuries.

WARNING!

This chapter is going to consist mainly of definitions of terms you will need to know throughout the book. Memorize them now, or you will be lost in later chapters.

Take this warning to heart. Many of the terms will be familiar ones: body, existence, activity, energy, process, purpose, and so on. But we are doing a scientific investigation here, and the terms have a very precise and technical significance. And even through the technical meaning may be somewhat similar to their ordinary use, if you don't have the technical sense in mind as you read later chapters, the ordinary meaning may seriously mislead you.

Let us begin by a definition of our main topic, and then try to make its parts clear:

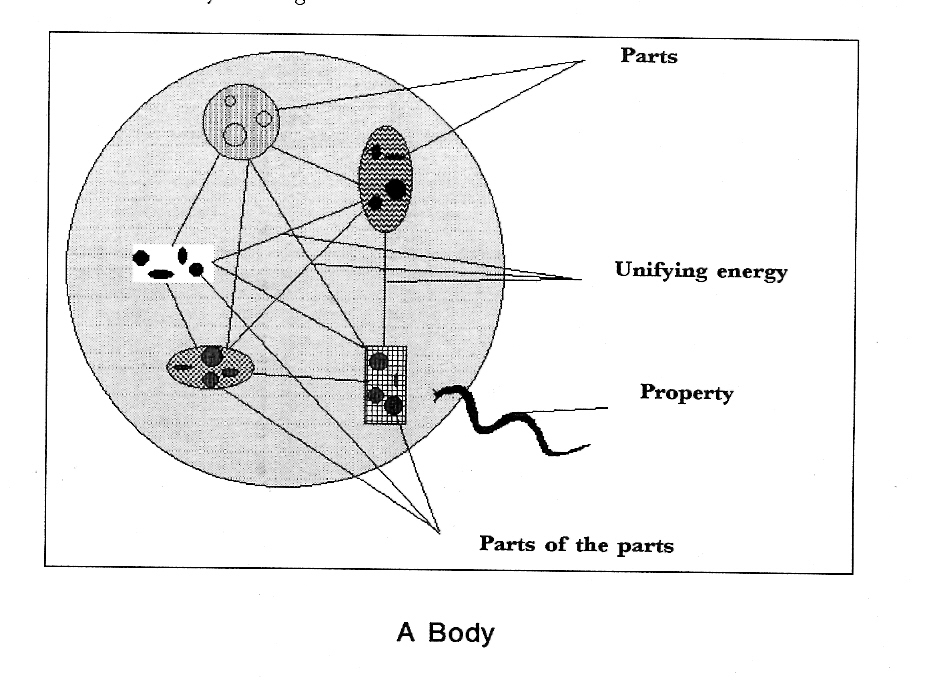

DEFINITION: A body is a real object consisting of various forms of energy tightly held together by a another form of energy.

In other words, a body is made up of energy, and so our first task will be to see what the reality of energy is.

[This topic is discussed at much greater length in Modes of the Finite, Part 1, Sections 3 and 4.]

In physics, energy is called "the capacity for doing work," and "work" is defined as "motion over a distance." This is a good example of the different orientations of philosophy and the empirical sciences. Physics is interested in discovering how much energy is used up in doing some work (i.e. in measuring it), and so is not concerned with what it is that does the work except as "the whatever-it-is that does work." In philosophy, we try to find out what it is that is being referred to by this indirect definition.

Even this road is a long and twisting one, and to make a long story short, it turns out that what physics is talking about is any sort of reality, provided that the reality in question is measurable.

So as a preliminary definition, we can say that energy is measurable reality.

Note, by the way, that it is a pure dogma of physical science, unsupported by any evidence, that every reality is measurable. As a matter of fact, we will discover evidence that certain undoubted realities cannot be measurable (or they would contradict themselves). This dogma is false.

But then what is reality?

It might be thought at first blush that anything we can talk about, or especially anything we can be conscious of, is a reality; but obviously this is not true. We can imagine and dream; and the objects of our dreams and imaginings are not real (at least as we imagine them).

But then if we notice the difference between imagining and experiencing what is real, we observe that in imagining, we are producing the images by ourselves (we are acting spontaneously, without responding to any information coming into us), and in experiencing the real world, we recognize that we are reacting to something.

Thus, if we say that something is real or exists, we say so on the basis of the fact that we are reacting to it directly or indirectly; and so it is either acting on us, or acting on something that is acting on us (which action on us is an effect, arguing to the existence--activity--of the cause). Anything that wasn't acting in any way couldn't be providing any information for us to know it, and so could not be known as real or existing.

From this we can say the following:

DEFINITION: Existence is activity. To be is to do.

Now this is "activity" in its broadest possible sense: doing anything at all. Even "being passive" is a kind of activity, since it is really reacting to some other activity. You don't have to do something to something else to be active or exist either; thinking is an activity, for example. The act of thinking is an "existence" of you (an activity), even though it stays inside you.

Note that existence does not depend on your knowledge of it; your knowledge of it depends on it. A thing can exist without acting on you (or anything else). In this case, you won't know that it exists, even though it does exist. But you can't know that something exists unless it is acting on you, either directly or indirectly.

Now activity is not simple; it turns out that all activities except one (the one called God) are limited or finite activities.

DEFINITION: Absolutely unlimited activity (i.e. activity that is neither of a certain type nor of a definite amount, but is infinite both in form and quantity) is called God.

There is only one possible such "pure activity," because if there were two different ones, then what made one differ from the other would be a limitation: a form of activity.

DEFINITION: The form of activity (or existence) is the limitation of activity to being only one kind of activity.

That is, it is the fact that the act in question is nothing more than the particular type of activity in question (e.g., thinking, seeing, heat, electricity).

Note that the form of activity is not something added to the activity (because this form of activity is less than what it would be if it were just activity). Hence, the form is not a reality in itself at all. How could it be? If it were a reality, it would have to be an activity, and then activity would be limited by itself. So the form is simply a way of considering an act that is not all there is to activity.

DEFINITION: Spiritual activity is activity which is either absolutely unlimited (God) or limited only in form and not further limited in quantity.

Spiritual activity is infinite with respect to quantity, but not necessarily absolutely infinite (or unlimited). The thought that "there is something," for instance, does not have any degree to it; it is not measurable. But it is clearly different from the thought that you are reading this page. Each is a different form of activity, but neither is greater or less than the other. We will establish later that thinking is in fact a spiritual activity and is not measurable.

DEFINITION: The quantity of a form of activity is the limitation of a given form of activity to being only a certain amount of this form of existence.

That is, the quantity is the fact that there is only this much of the form of activity in question (e.g., the temperature of heat, the charge of an electrical field).

The quantity of an activity makes that form of activity measurable.

Note several facts here:

1. The quantity, like the form, is not something in itself; it is merely a limit. In fact, the quantity is the limit of the limit called the "form," and so in itself it is doubly nonexistent. Think of the temperature of heat. It is clearly not something that you add to heat to make only this much of it; it is just that the heat "stops," as it were, at this degree.

2. It is not necessary for existence (or activity) to have either of these limitations. Things can be real without being measurable, and even without being a specific kind of thing.

3. If a given activity has quantity, it is then measurable, because numbers can be applied to it. Spiritual activities are not measurable.

[This topic is discussed at great length in Modes of the Finite, Part 2.]

I said in introducing this chapter that energy is any sort of reality that is measurable. Well, reality is what exists, and existence is activity; and we now know that quantity is the aspect of some activities which allows them to be measured; and so it follows that:

DEFINITION: Energy is any form of activity which is limited in quantity.

Note that energy is not the quantity (the limitation). The quantity is the energy's amount or degree; the energy is the act which is limited to this degree. But to be called "energy," activity has to have a quantity. There's nothing mysterious about this; it's just that we don't call spiritual acts "energy," because we reserve "energy" for acts that are measurable.

Energy is a "catch-all" name. There is not some special thing called "energy"; energy refers to any activity, provided the activity is measurable (is limited quantitatively). Thus, heat is energy, light is energy, mass is energy, electricity is energy. All these are forms of energy (because they are forms of [measurable] activity).

In other words, energy is non-spiritual activity.

Thinking, as we will see, is not a form of energy. It is like energy in that it is a form of activity; but it is unlike energy in that it has no quantity and therefore cannot be measured. "How much" thinking is going on is a meaningless question.

The reason energy is called "the capacity for doing work" is, of course, that you can't move something (or do something analogous) without being active, whatever form the activity happens to take. And energy, being limited quantitatively, is used up by doing work, and so you can measure how much energy did the work by measuring the work done.

Spiritual acts, by the way, are not "used up" by doing things, and so the "work" done by them does not indicate "how much" of them there is. When a choice of yours pushes around some electrical impulses in your brain, this does not take some activity away from the choice-act; the choice-act, being only a kind of activity without a quantity cannot lose "some" of itself; it either is or it isn't; it admits of no degrees by which it could be "less."

HISTORICAL SKETCH

Plato (c. 400 B.C.) was the first philosopher to notice the spiritual as not bound by the "conditions of space and time" (which we have learned in the centuries since means measurability); and he spoke of "Aspects" (later translated "forms") which were the "realities" of the observable things we see. He thought that the "form" of something like light was a spiritual thing which had individual "lights" sharing in it more or less imperfectly.

Aristotle (Plato's pupil, c. 350 B.C.) discovered that what Plato called "form" was really "activity," (for which he invented the word that we took over as "energy"); but he thought the acts were acts of some "stuff" or "matter" things were "made of." The act made the matter a kind of something, and the matter made the act an individual; he thought of the form as limiting the matter, and the matter in a different sense as limiting the form.

Plotinus (c. A.D. 250) noticed that the forms were limitations, but not of matter; matter was the limitation of form. The form was a limitation of something that could not really be named, but which he referred to as The One, and thought of as God. With Plotinus, however, the notion of activity was more or less lost; reality was a kind of static something-or- other.

St. Thomas Aquinas (c. 1250) got back the Aristotelian notion of "activity" or "activeness", and was the one who saw that God was pure, unlimited Activity, that the "form" was nothing but a limitation of activity and "matter" was a limitation of "form." He called limitation "potency" for reasons we don't have to go into. St. Thomas also saw a connection between "matter" and "quantity."

The whole of this investigation was stopped, however, shortly after the Renaissance, when René Descartes (c. 1625) began approaching "reality" from the point of view of consciousness. No one, right up to the twentieth century, paid any significant attention to the distinction between imagining (creating acts of consciousness) and perceiving (having reactive acts); and so "reality" philosophically wallowed in the morass of "the object of consciousness," and philosophers spoke of "the real world" as if it were just a fancy type of imaginary world.

It is only now that we have got round the problems of knowledge initiated by Descartes and "rediscovered" what any five-year-old knows, that there really is a real world out there, that we can resume a scientific approach to the study of reality.

During the Renaissance, Galileo (c. 1600) started the empirical sciences moving ahead by stressing measurement (which he thought got around problems of knowledge), and so discoveries were made about energy, and all sorts of "forms" were found to have their own quantities.

These advances, however, went along independently of the progress--there was progress--in philosophical investigations; and it is only now that we can begin to fit the two together again. Interestingly enough, however, science is now, in the deeper levels of physics, running up against the problem of knowledge which it avoided for four hundred years. There are certain experiments which seem to indicate that if you decide to measure the act one way, it is one kind of thing (and is in two places at once), whereas if you decide to measure it a different way, it is a different kind of thing (and in only one of the two places it is in). Physics now needs the results of the philosophy of knowledge, just as philosophy needs the results of the sciences, before both can catch up to where each should be.

We saw at the beginning of this chapter that bodies are bundles of energy, united by a special form of energy. So now we can say that bodies are bundles of different forms of activity, each of which has its own quantity; and all these forms of energy are held together by a form of activity which has its own quantity.

Bodies are special cases of systems. Any system is various forms of energy (or sub-bundles of subsystems of various forms of energy) held together by a unifying energy. If you refer back to the definition of "body" earlier, you will see that this means that a body is a tightly unified system. What then is the difference between the two?

A body is a system which is so tightly unified that it behaves (acts) more like a single unit than a number of interconnected objects.

There is something mysterious here. Even though the body is many activities, they are interconnected in such a way that it acts like one reality (activity) in some sense. Thus, if you hit someone with your hand, it is you, first and foremost, that did this act. A body exists primarily as one act, secondarily as many acts.

This one-and-not-one aspect is due to the body's finiteness; but it is not our point here to investigate this further, so let us go on.

In general, the dividing-line between a system and a body is somewhat arbitrarily drawn. If the object in question has properties that are different from the properties of the individual parts, then we tend to call it a single body; if it doesn't do anything much that can't be explained by a simple sum of the parts, then we call it a system.

The extremes are pretty obvious. The solar system is a system, even though it is held together by the sun's gravitational field. An animal is a body, even though it has many different organs. In the case of the solar system, the planets are pretty largely independent of one another; in the animal, the parts exist for their function in the animal as a whole.

But is a stick a body or a system of bodies (the molecules of the wood)? Here we are in a borderline case, and it depends on how you want to look at it. In ordinary usage, we think of the stick as one thing; but when you break it in two, nothing much has happened to it--whereas if you "break" a molecule in two, you get two entirely different substances.

But the problem of when something "deserves" to be called a body instead of a system is not something we have to worry about. What we are concerned with is what a body is (or what makes a body a body, if you will). And it seems that a body, as opposed to a system, is just a system whose unification is what is most significant about it.

This unification, of course, is brought about by some form of energy, as I said. It is this unifying energy which gives the distinctive structure to the body, whose form makes it the kind of body which it is, and whose quantity gives the body its fundamental energy level as a whole.

DEFINITION: The unifying energy of the body is the energy connecting the parts, making them behave together as a distinctive unit.

This unifying energy it is basically the interaction of the parts as they "act together as one." It is simply the energy unifying the body; the energy connecting the parts; it is how the body is held together, so to speak. In an atom, for instance, the unifying energy is the internal electrical field connecting the electrons and the nucleus.

Since this unifying activity is in fact a form of energy, then obviously it has a form and a quantity. The form of the unifying energy is the way the parts are interacting; its quantity is the degree of that interaction of the parts.

Note that it is the form of the unifying energy of a body that makes the body the particular kind of body that it is. Bodies do not differ in kind by reason of the parts that make them up, but by reason of how those parts are arranged or "structured" (in other words, what they are doing to each other). A human being differs from a lion, say, not in the chemicals that make up his body (the parts), but in the fact that these parts have different internal relationships as they make up the organs which in turn make up the body. And these "internal relationships" are nothing but the particular form of unifying energy. The structure of a body is something dynamic, not static; it is the way the parts are behaving toward each other.

Practical consequence 1

A body is a human body, not because it has certain parts, but because the parts are interacting in a human way. Any body with this type of interaction among the parts is a human body, whether it "looks" human or not.

Thus, Black people are human, though they look different from White people, because (as can be seen from the fact that Blacks and Whites can marry and have children with the characteristics of both) their bodies are organized in the same way. It is also clear that the bodies of fetuses are organized in the same way as the same body is organized after birth; why else does the body have organs (such as eyes or hands) that make no sense to his life inside the uterus? Hence, human fetuses and even human embryos are in fact human beings.(1)

Note secondly that, since the unifying energy's job is to knit the parts together into a unit, the unifying energy is not directly observable from outside the body. You have to argue to the fact that it is there because of the observable behavior of the body. Hence, no one will ever get an instrument which will be able to measure whether Jews or Japanese or fetuses are human, because if such an instrument were introduced into the body to detect the unifying energy, the unifying energy would detect it and refuse to interact with it; it would just be another body inside the body in question, and would be rejected as a part of the body.

But this doesn't mean we can't know what kind of unifying energy a body has; its observable activities will reveal it.

Note thirdly that the quantity of the unifying energy accounts for the differences in bodies of the same type. That is, you and I differ as humans in that your unifying energy (which is the same kind as mine) has a different degree from mine; our bodies exist at different energy-levels.

Note fourthly that the quantity of the unifying energy determines the energy-level of the body as a whole. Just as the form of the unifying energy determines the kind of body, so its quantity determines the basic amount of energy that is in the body as a whole.

Practical Consequence 2

Since "equal" is a quantitative term, it follows from what was said above that no two human beings are created equal.

We are all (qualitatively) the same (human); but each of us is more or less human than our neighbor. This is obvious. We will see shortly that the body reveals itself in its behavior; and some of us can do a great many human acts and do them very energetically, and others of us can only do a few. No two of us exist at exactly the same energy-level of humanity.

Before you get nervous at this, let me note that human rights depend on the form of the unifying energy, not its quantity. You have a right to life and liberty because you are a human being, not because you are a well-developed human being. And if you should be knocked out and be unconscious and not able to exercise any of your human behavior except breathing and heartbeat and so on, you would still be a human being, and would still possess all your human rights.

In that sense, each of us is "just as much a human being" as any other human being. But in the strict sense, a child is not as much of a human being as he is when he is an adult, and his body has reached its proper energy-level; and even when an adult, he may very well be not as great a human being as someone more genetically gifted.

THEOLOGICAL NOTE

Since the form of the unifying energy) makes the body the kind of body which it is, then this would allow us to interpret something that Catholics believe in the following way: When the priest, in the person of Jesus, says of bread, "This is my body," and of wine, "This is my blood," then Jesus himself (by his divine power) takes over the function of uniting the elements of the bread, (probably mimicking the unifying energy). Hence, the "bread" is not really bread any more, because its unifying energy is not its own but Jesus' activity--and so it really is Jesus.

Since there is only one Jesus, then if he does this to many pieces of bread, then they are all one and the same body (because they are united by one and the same "unifying activity"--Jesus' act), and are not "many Jesuses" any more than the many cells of a normal body are many bodies.

Of course, there is no evidence apart from Revelation that Jesus does this. The point is that it is not unthinkable that if he is divine, he could do it, and if he does do it, then the bread really ceases to be bread, even though all the elements and properties are there, and is really Jesus.

DEFINITION: Parts are the subunits of a body, each of which has its own form of organization; but the parts are all subordinate to and under the dominance of the energy unifying the body as a whole (i.e., the unifying energy).

In a system, the "parts" are the primary aspect; but then they are called "elements of the system" rather than "parts."

Since a body is many parts cooperating, and nature as it were, to form a complex unity, it would not be surprising to find that the unit itself acts in complex ways.

DEFINITION: Properties are the way a body acts because it has both (a) a certain unifying energy and (b) a definite set of parts.

DEFINITION: The nature of a body is the body looked on as the "power" to perform the acts which are its properties.

Thus, for instance, it is the "nature" of hydrogen to combine with oxygen to form water, or to have a certain spectrum when excited, or to be a gas at room temperature, to be colorless, to have a certain mass, etc. That is, it is because the hydrogen molecule consists of two hydrogen atoms (the parts, having their own internal structure--their own "sub"-unifying energy) united by a covalent bond (the unifying energy of the molecule as such) that it acts in certain ways in response to various forms of energy.

Properties, then, are basically distinctive energies of a body, which it performs (all energies are acts, remember) in various circumstances; properties reveal what is acting, and this is why it is useful to speak of the "nature" of things as revealed by their acts.

Note that properties are not parts. The hardness of a piece of wood, its size,

shape, color, are in fact behaviors of the wood in response to energy around it; its parts are the atoms that make it up.

Note that properties are not parts. The hardness of a piece of wood, its size,

shape, color, are in fact behaviors of the wood in response to energy around it; its parts are the atoms that make it up.

All of what we think of as "characteristics" of something are in fact acts it performs; behaviors of it. These are its properties. The act you are now performing as you read this (your reading) is a property of you as this individual. It is an act which reveals what you are--your individual nature (something which can do this because of the way these parts are organized).

We usually restrict the term "behavior" to properties of animals, because these properties are controlled by the consciousness of the animal. Still, it is useful to call all properties "behaviors," since this stresses the idea that the property is not something static, but what the body is doing.

HISTORICAL SKETCH

Aristotle (350 B.C.) initiated the study of what we are talking about. He spoke of the "reality" of something as opposed to its "accompaniments," and these words were mistranslated into Latin as "substance" and "accidents." The "reality" corresponds either to what I have called the "unifying energy" or to the body as a whole, and the "accompaniments" are what I called the "properties." He referred to the "reality" (the "substance") as the "primary activity" and the "accompaniments" as "secondary acts." He also defined "nature" almost exactly as I have done just above.

In the Middle Ages, "accidents" were defined as "that which exists in another," meaning that they were the existence (the act) of something (the "substance") rather than realities in their own right--as color is always the color of some body. The "substance" was then defined as "that which exists in itself," meaning that it wasn't an act of something else.

There was a good deal of confusion about whether the "substance" was the whole object or the unifying activity of the object, because the word was used in both senses. The "substantial form" was the form of unifying activity and also the form of the thing as a whole (which, of course, it is in my system also--but in those days, it was not clearly seen that they were not the same in concept). It looked as if the "substance" united the "accidents," when in fact it unites the parts. In my terminology, there was confusion between the parts and the whole and the body and its properties. (This was added to by the fact that the atomic theory of bodies was not developed, and they were considered to consist of a continuous mass of stuff.)

Descartes (1625), who approached reality through thought, probably did more damage to the investigation of reality by his misunderstanding of "substance" than anyone else has ever done before or since. He took the definition, and instead of trying to discover what effect it was intended to explain, he simply said "substance is what exists in itself (or is independent)" and concluded that if you had two "clear and distinct ideas," (i.e. concepts that were, among other things, independent of each other), then they referred to two different "substances." Since "thought" was different from "extension" (spreading out in space), then it followed that a mind was a different substance from a body; and therefore the human being was not one thing, but two--or rather, a human being is a mind, but with the peculiarity of being inside this other object called a body. So we "have" bodies the way we "have" clothes.

Baruch Spinoza (1650), who came shortly after Descartes, took his notion of "substance" as "independent" and said that, since we all depend on God, there is really only one "substance," and we are all "modes" (modifications) of Him. (You can see how far away from the original notion of how the parts of a multiple unit are unified we have come.)

Gottfried von Leibniz (1670), about a century before the founding of our nation, interpreted "substance-independent" as meaning that there are many "substances," but they are all "independent" of each other; and each "substance" actively produces all of the events of its life from within it, without either acting on or being acted on from anything outside--except that the "substance of substances" (God) picks out the set of "substances" that fit together, so that as John performs the act of speaking-to-Frank (without actually acting on him), Frank happens to be performing the act of listening-to-John (sort of like a dream, without actually being acted on by John's voice). This "preestablished harmony" makes everything work out just as if substances acted on each other.

By this time, people with any common sense were saying that all of this speculation was a colossal waste of time, however brilliant the theories were as exercises of ingenuity. And so John Locke (1675) in England thought we ought to forget about the notion of "substance" altogether, since after all we never see "substances," but only assume that they exist because the properties seem to go around together.

And this was brought to its logical absurdity by David Hume (d. 1776), who held that for all we know, we aren't any more than just a series of impressions strung together. We assume that we have minds and bodies; but after all, we never saw either of these "substances," and so we might just be the "properties" called "ideas"; and we just get into the habit of calling this set George Blair.

From then till now, all but the unsophisticated people have been locked into (or should I say Locked into) their own consciousness, and consider that to talk of a "real self" that is doing the thinking and the running and so on is to be "naive."

And all because the effect that "substance" was trying to explain got lost sight of.

In any case, the term "substance" became preempted by chemistry, where it means something still different from all that we have seen. A "substance" in chemistry corresponds to what I would call a "kind of body." That is, it is any body with a given form of organization. Thus, all instances of sulfur are the same (chemical) substance; though each is a distinct body.

For this reason, I do not use the term "substance." It is a mistranslation of the Greek to begin with, and it has been so abused that it is useless as a word any more.

One of the most obvious characteristics of bodies is that they change. All the sciences, in fact, deal with changes; but again their orientation is in discovering how the particular type of change they are interested in takes place, while we are concerned with what change implies about the nature of the changing body.

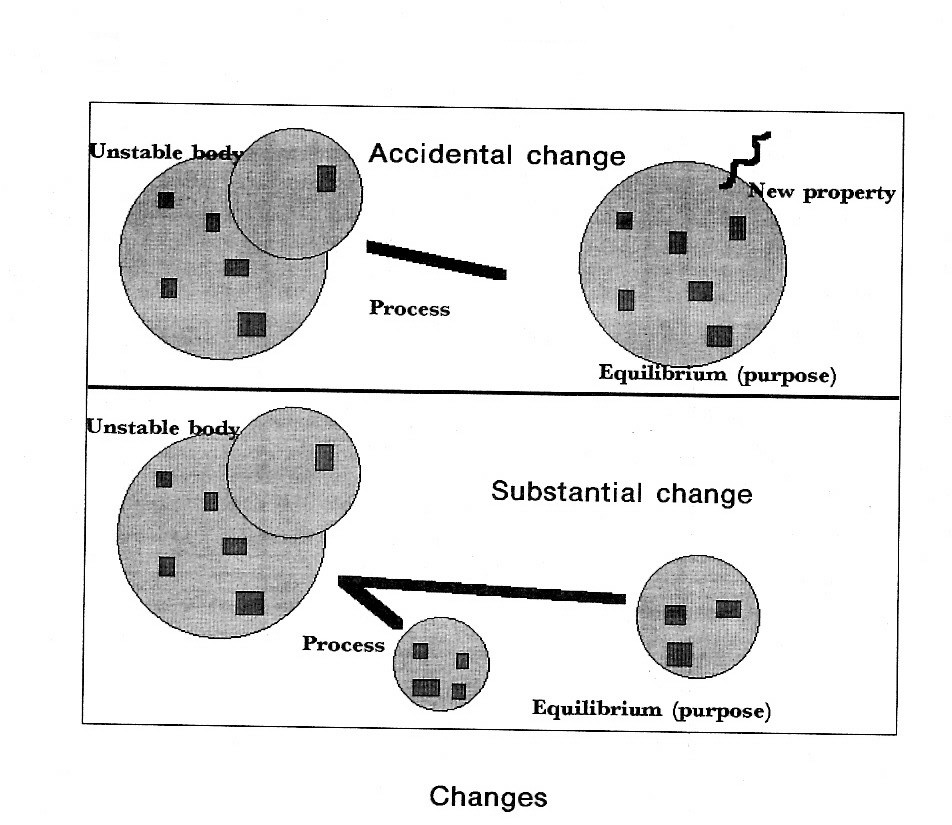

DEFINITION: A change is an act whereby one and the same body becomes different from itself.

If this sounds mysterious, it is. If there is total sameness, then obviously no change has taken place. But if the product of the "change" is totally, in every sense different from what existed before it, then there is no sense in which what came before "turned into" or "became" what resulted. That is, when the magician puts the handkerchief into the hat and pulls out a rabbit, we know that a replacement has occurred, and the handkerchief didn't really change into a rabbit. Similarly, if some object were annihilated (so that nothing was left) and some other object created (not out of any part of it), then the first just disappeared; it didn't "become" or "change" into the second.

Hence, change has to involve both sameness and difference.

2.3.1. Equilibrium and instability

Once more we have to make a very long story short here. In order to account for how it is possible for changes to occur, we have to note that there are two possible conditions a body can be in:

DEFINITION: Equilibrium is the condition in which the total energy of the body is compatible with its unifying energy.

That is, the body's unifying energy has a definite amount. Since it holds the body together, then this implies a certain amount of energy in the parts. When the sum of the parts' energy is the right amount, then the body is in its natural condition.

Note that, since equilibrium is the natural state of a body, a body in equilibrium will continue to exist in this way unless something from outside interferes with it.

DEFINITION: Instability is the condition of a body in which the total energy of the body is incompatible with its unifying energy.

If a body's parts have too much or too little energy, then the unifying energy cannot unify it (or cannot unify it properly). Hence, the body is in an unnatural condition.

Note that a body cannot exist in an unstable condition. It must get rid of the instability.

For example, let us say you add heat to a piece of wood. This puts it into an unstable condition, and so it can't exist as it did before. The reason is that the instability is an internally contradictory condition, and contradictions can't exist.

Hence, as soon as the body is unstable, something must happen. Now, depending on the degree of the instability (and various other things, which we can't go into), the wood can do one of two things: it can somehow get rid of the excess energy (by producing a property it didn't have before), or it can restructure itself or acquire a unifying energy (a different type of interaction of the parts) that can handle the new energy-level.

DEFINITION: An accidental change removes an instability by keeping the same unifying energy and getting rid of excess energy (or acquiring energy to make up the deficit).

Thus, when wood gets hot, the molecules move faster, hitting each other and getting rid of their excess energy; and the outside molecules, of course, hit the air, and so dissipate the excess energy out of the wood itself. When the wood reaches the temperature of its surroundings, then it is in equilibrium again and stops emitting heat.(2)

Note that the result of an accidental change is the same type of body, but different properties. It is the same type of body because it has the same form of unifying energy. It has new properties because of the activity it is performing in getting back to its equilibrium condition.

DEFINITION: A substantial change removes an instability by restructuring the body with a new type of unifying energy.

Note that the result of a substantial change, then, is a new kind of body, since the type of body depends on the form of the unifying energy. The result may in fact be several bodies, since the body could not hold itself together at the energy-level it had when unstable.

Thus, if you heat the wood and it just gives off heat, this is an accidental change. If you heat it enough, however, the parts can no longer "stick together" in a "woody" way, and the thing catches fire and burns, resulting in carbon dioxide, water vapor, and ashes, and so on. This, of course, is a substantial change.

Note that an interaction of several bodies can be in some respects an accidental change and in other respects a substantial one. When you eat an egg, for instance, you undergo an accidental change (because you acquire energy and parts to replace what you lost--and are still yourself), while the egg undergoes a substantial change (because its form of unifying energy has disappeared once the parts become parts of your body).

From the historical sketch, dealing with bodies, you can see where these terms came from. They don't have quite the problem that "substance" and "accident" themselves have, so I have kept the traditional terms.

Note that changes always go from instability to equilibrium. To get something into an unstable condition, it has to be forced from outside.

The reason for what I said just above is, of course, that instability is an unnatural, self-contradictory condition of a body and equilibrium is its natural condition; hence, any unstable body is going to be headed toward some equilibrium or other.

DEFINITION: The purpose of any change is the equilibrium at the end of the change.

That is, purpose is not "to get to" the end, but is the end itself. It is in fact equilibrium; but it the equilibrium that ends some change. "To get to" equilibrium defines the direction of the change, not its purpose; the purpose is where it is going to end up.

NOTE WELL

The purpose is simply the end of the change, nothing more.

This does not mean that the unstable body "knows" and "desires" a particular equilibrium; it is just that a given instability (discrepancy between unifying energy and total energy) is apt to imply a given equilibrium as the "shortest way" to get out of instability. This predictable future state is what I mean by a "purpose" here; and I am not trying to attribute desires to inanimate objects.

Actually, as we will see much later, human purposes are analogous to these "natural purposes," rather than the other way around. By desiring something or imagining a future state, we can create an instability within our bodies, which then has the purpose of being in that state (just as any body in an unstable condition does). The difference between natural and human purpose, then, is how the instability got there, and not in what happens once it's there.

Note that only changes have purposes. Equilibrium has no purpose; it just is. If anything, equilibrium is a purpose; it doesn't have one.

Be aware of this. The purpose of something is its "meaning" only for something which is incomplete in itself and is "headed somewhere." If it is all that it can be, then it contains its meaning within it. A being's existence is its ultimate "meaningfulness."

But then what about the act of changing?

DEFINITION: Process is the act of changing; it is the property which is the change itself.

Acts in equilibrium (ones that stay the same) are called "acts" or "forms of energy," not processes. Process is the act of becoming different. Thus, color is a form of energy, growth is a process; mass is a form of energy, movement is a process; electricity is a form of energy, decay is a process.

Processes have direction (toward their purpose), and forms of energy do not. Science calls processes "vector quantities" (by which it means acts with quantity and direction) and forms of energy "scalar quantities" (acts that have quantity but no direction).

HISTORICAL SKETCH

Heraclitus (c. 500 B.C.) was the first "process philosopher"; he thought all activity was process, and that change is the only "real" reality, driven by what he called "fire," which, as he meant it, is not too far away from what we have called "energy."

Parmenides (c. 500 B.C.), who lived more or less at the same time, however, saw that "nothing" or "non-reality" is not a something that has the property of "not existing"; negative statements are only the equivalent of "it is false to say that..." But he then drew the logical conclusion of this that change is impossible. What would something turn into? What it isn't. But "isn't" isn't something it can turn into; hence "It turned into what it isn't" is another way of saying, "It is false to say it turned into something." (He also held that difference among realities is impossible, because the respect in which they differ can't be reality [which they have in common] so must be non-reality [which is another way of saying "it is false to say there is a difference"].)

Plato (400 B.C.) solved the dilemma of Heraclitus and Parmenides by holding that the spiritual world of Forms was a world in absolute equilibrium, and is the "world of reality," and the world that we perceive (which only shares in reality) is the Heraclitean world of change.

Aristotle (350 B. C.), who held that forms are activities of "matter," explained change by talking about "instability" in the following terms: something is "in potency" to be something else, he said, when its matter (for some reason) "lacks" or "needs" a different form from the one it had. At this point, its "end" is outside it, and it changes until it "has its end in itself," (which is practically speaking what I called "equilibrium" above). He was the one who noticed the natural purpose I defined above.

With the middle ages and St. Thomas Aquinas (1250), the theory of activity went beyond form to activity itself, of which form was a limitation, with matter as a limitation of form. Instability (being "in potency") then amounted to a discrepancy between an act and its limitation; and the new insight led to the assumption that purely spiritual beings could change accidentally, but not substantially, because they had no matter.

This, however, is a fallacy, because the "substance" can't be unstable, since there are no parts and unifying energy in a purely spiritual being.

But there were more serious problems. Because of the Theological orientation of the Middle Ages, the "purposiveness" inherent in instability's "seeking" equilibrium was tied to the supposed "purpose" God had in creating the universe in the first place--which was assumed to be a good purpose--and so it was held that "everything has a purpose," (even equilibrium) and that "everything seeks God," and "everything naturally acts for the good" and that "the universe and every thing in it is all following a preconceived plan leading up to God's glory and its perfection."

In other words, so much was read into the predictable tendencies of things, giving inanimate objects quasi-mystical "desires" that longed for fulfillment of some Divine plan that only Theologians could comprehend, that when science came into its own during the Renaissance, it not surprisingly dropped "teleology" (studying purposes) altogether, and only talked (it thought) about changes in terms of the energy that caused them to begin.

But this has been a handicap to science, because of course changes have predictable results--and science has always been using these. For instance, a mixture of hydrogen gas and oxygen can be in equilibrium as a mixture of gases; but if you introduce energy of any form (heat, an electrical spark, sudden compression, etc.) the result is the same: water. Obviously, the result is because of the structure of the hydrogen-oxygen mixture, not because of the energy introduced. Hence, the instability is what determines the result--and therefore, Aristotle was right in talking about natural purposes.

Once again, therefore, with the working through of the philosophical problems allowing us to get back to a rational view of reality, we can let philosophy help science get away from the difficulties it got itself into in its attempt to break away from the absurdities that philosophy had got itself into.

What has been said in this chapter is true of all bodies, whether living or inanimate. In the next chapter we will get into differences between the two kinds, and try to see what is distinctive about the nature of living bodies as living.

A body is an object made up of forms of energy tightly united by its unifying energy. Energy is any existence (or activity) which is limited in form (the kind of act) and quantity (the amount of the kind of act). Spiritual existence is either God (absolutely unlimited activity) or activity which is limited only in form.

Bodies have parts, which generally are subunits with an energy unifying them; but all parts of the body are united by the unifying energy of the body as a whole, which has a form, which makes the body the kind of body which it is, and a quantity, which makes the body the individual example of this kind of body, existing at its own energy level.

A given body, with given parts interacting in a given way and to a given degree, will behave distinctively in response to the energy falling on it; these behaviors are called properties, and they reveal the nature of the body (the distinctiveness as the "ability" to perform the acts in question).

A body's unifying energy "needs" a certain total energy in the body as a whole in order to hold the body together. When the body has this energy, the body is in equilibrium, and when it exists at a different energy level, the body is unstable, and cannot exist. The body then either adjusts the energy-level (accidental change) or restructures itself with a new unifying energy (substantial change) and becomes a new kind of body. The equilibrium at the end of the change is the change's purpose. Only changes have purpose; equilibrium just is. The act of getting from instability to the purpose is called a process.

Exercises and questions for discussion

1. But can't our dreams be the real world and what we call "waking life" the unreal one?

2. A body is many activities, and so many realities. But the book says that it is "really" one reality. How can it be both?

3. What is the difference between a human being and a human corpse? How can you tell?

4. If properties reveal the nature, then is everything that looks like a human being a human being, and everything that doesn't look like a human being not a human being?

5. Does everything have a purpose?

Notes

1. 1Note that a fetus or embryo is not part of the mother, because it does not function for the benefit of the mother as an organism; and so it is not integrated into the unit which is the mother's body, but is a parasite living inside it, much as a tapeworm or a tick is not a part of the host organism.

2. 2There are complications here, because "thermal equilibrium" is not perfect equilibrium; but let it serve as an illustration.