Note that properties are not parts. The hardness of a piece of wood, its size,

shape, color, are in fact behaviors of the wood in response to energy around it; its parts are the atoms that make it up.

Note that properties are not parts. The hardness of a piece of wood, its size,

shape, color, are in fact behaviors of the wood in response to energy around it; its parts are the atoms that make it up. Living

Bodies

By

George A. Blair

Copyright © 1993

by George A. Blair

Chapter 1: Evidence and Knowledge

1.1. What the book is about

1.1.1. Difference from biology and psychology

1.1.2. Plan of the book

1.2. The disease of the age

1.2.1. The source of the infection

1.2.2. The cure

1.3. Science

Summary

Exercises

Chapter 2: Bodies

2.1. Energy

2.1.1. Existence or activity

2.1.2. What energy is

2.2. Bodies

2.2.1. Properties

2.3. Changes

2.3.1. Equilibrium and instability

2.3.1.1. Purpose

Summary

Exercises

Chapter 3: Properites of Living Bodies

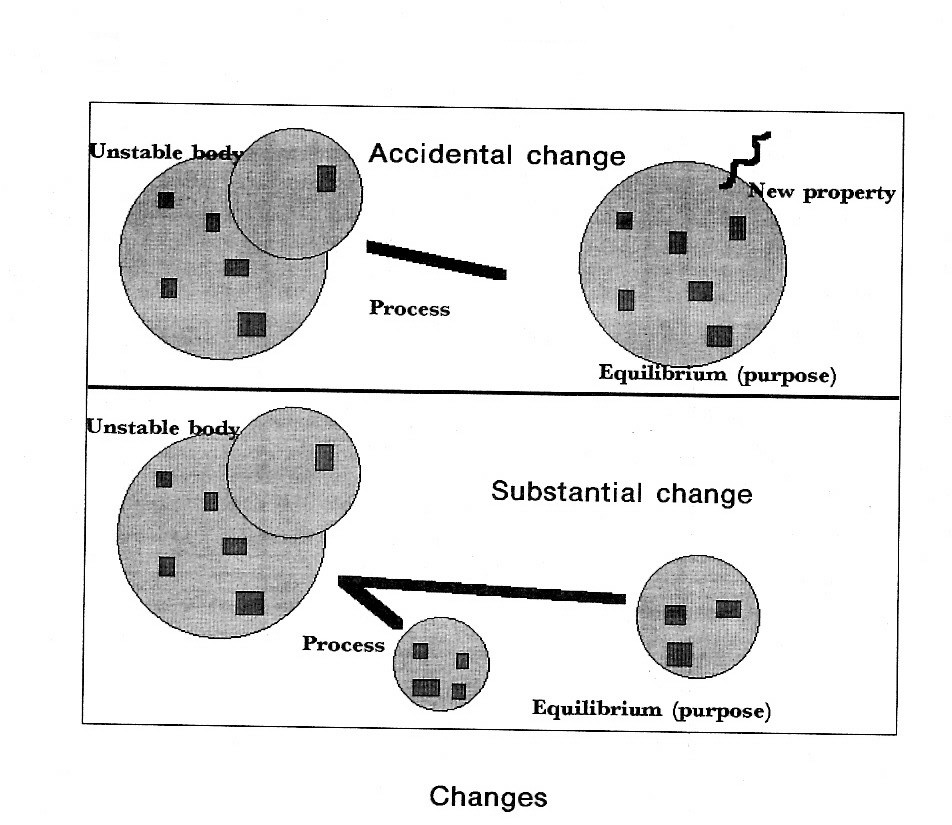

3.1. Life vs. the inanimate

3.1.1. Nature of the inanimate

3.2. Nutrition

3.2.1. Biological equilibrium

3.3. Growth

3.4. Reproduction

3.4.1. Evolution

3.5. Repair

Summary

Exercises

Chapter 4: The Nature of Life

4.1. The basic conclusions

4.1.1. Essential superiority

4.1.2. Evolution revisited

4.2. Life

4.3. The soul

4.4. Faculties

Summary

Exercises

Chapter 5: Consciousness

5.1. Evidence for consciousness

5.2. Self-transparency

5.3. Consciousness as one act

5.4. Consciousness as double itself

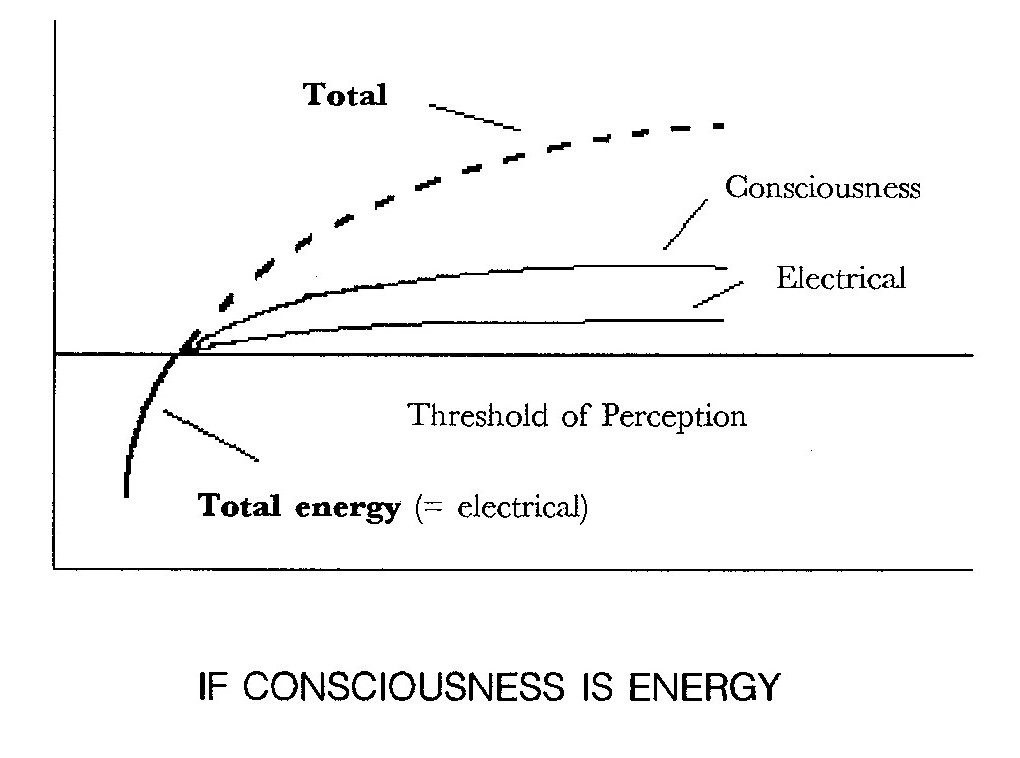

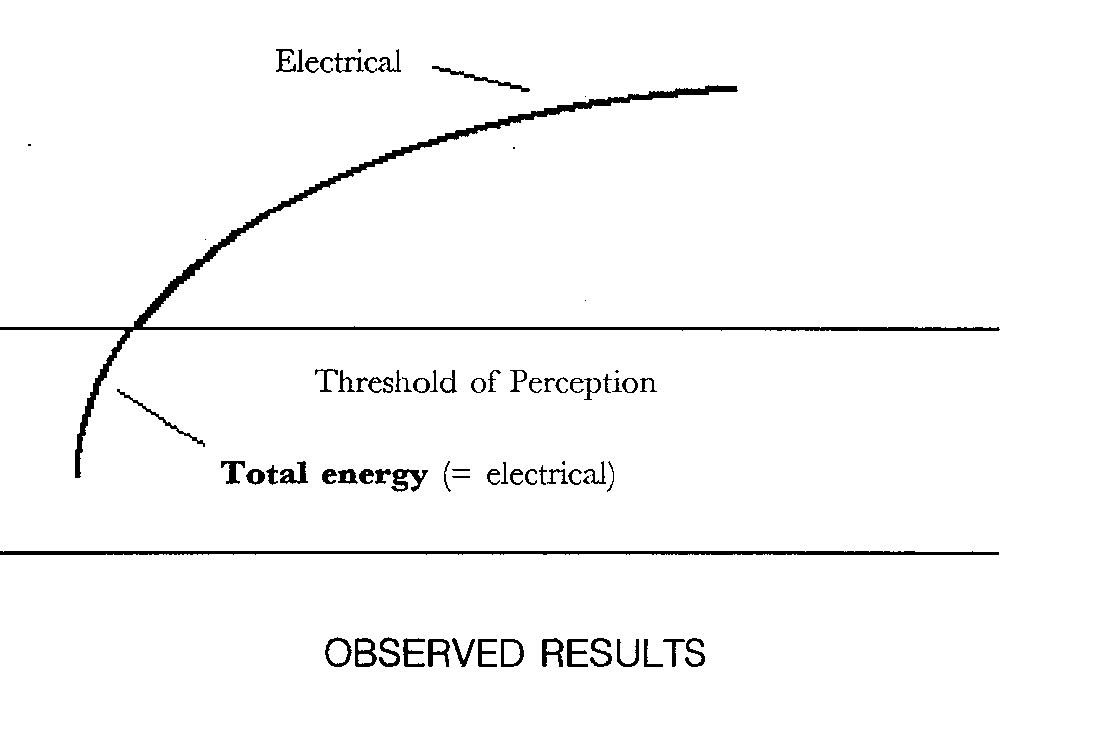

5.4.1. Confirmation: consciousness as not energy

5.4.2. Consciousness as spiritual

5.5. The faculty of consciousness

5.6. The soul of a conscious body

5.6.1. Consciousness and the computer

Summary

Exercises

Chapter 6: Sensation

6.1. Reactive consciousness

6.2. Evidence that sensation is energy

6.3. The solution: sensation as immaterial

6.4. The sense faculty

6.4.1. The "external senses"

6.4.2. The processing acts: the "internal senses"

6.4.2.1. The integrating function

6.4.2.2. Imagination

6.4.2.2.1. Hallucinations and dreams

6.4.2.3. Sense memory

6.4.2.4. Instinct

Summary

Exercises

Chapter 7: Thinking

7.1. The approach

7.2. Understanding vs. imagining

7.2.1. Understanding vs. generalized image

7.2.2. Understanding vs. association

7.3. What understanding is

7.3.1. Concepts

7.2.1.1. Abstraction

7.3.1.2. Universality

7.4. The "process" of understanding

7.5. Reasoning

Summary

Exercises

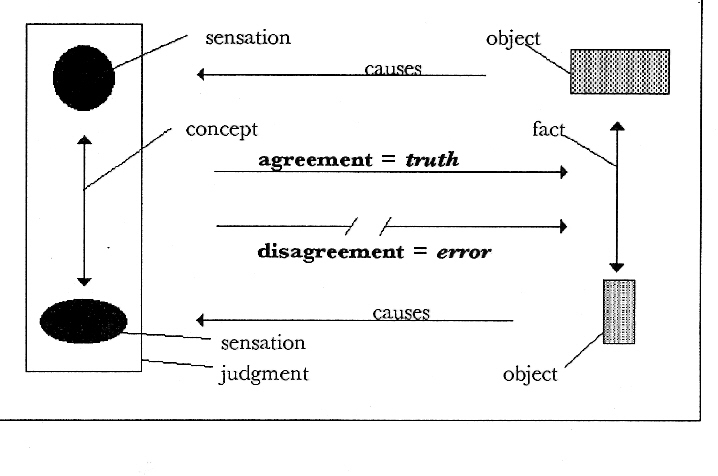

Chapter 8: Truth and Goodness

8.1. The problem

8.2. Toward a solution

8.3. Facts

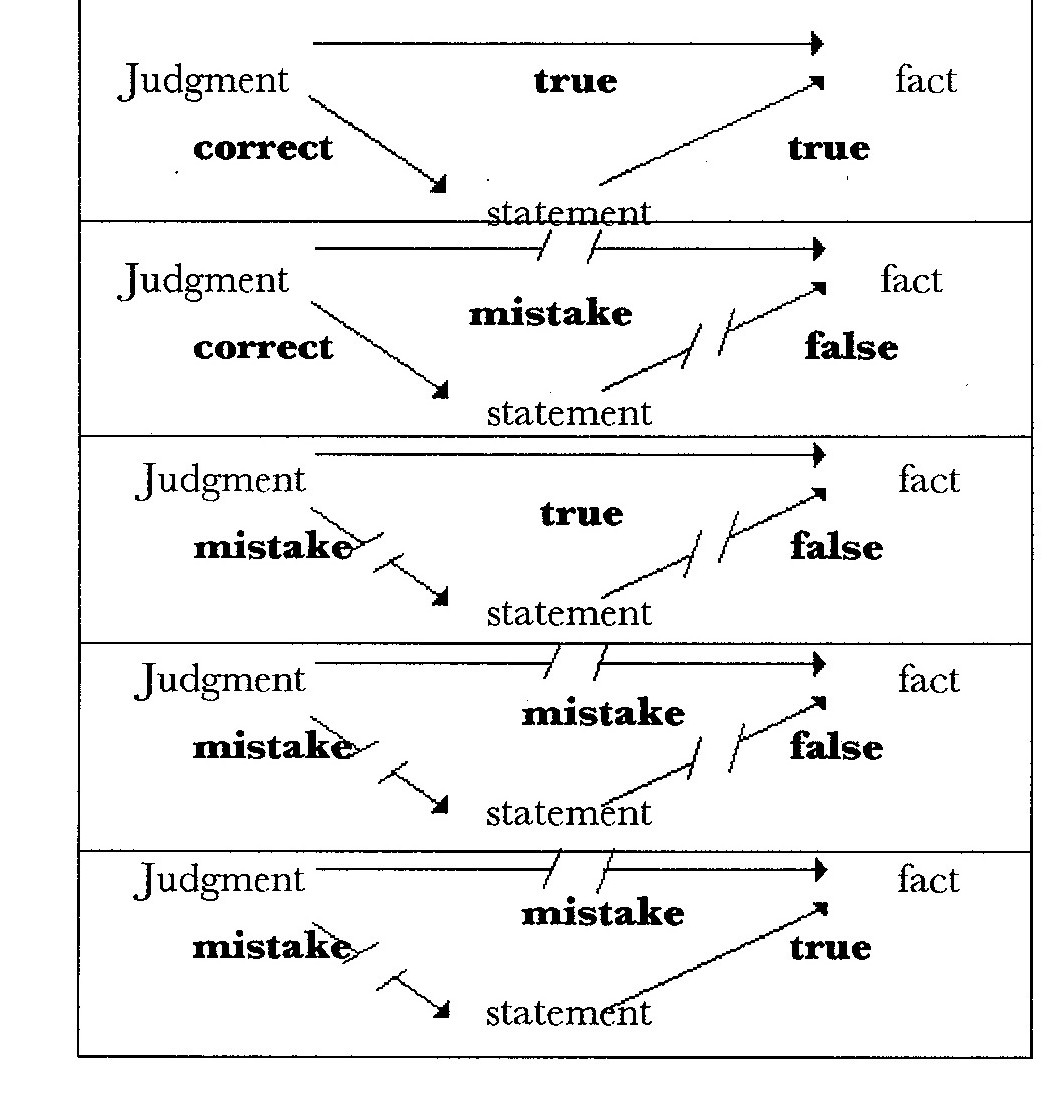

8.4. Truth

8.4.1. Truth vs. falseness

8.4.2. Truth vs. lying

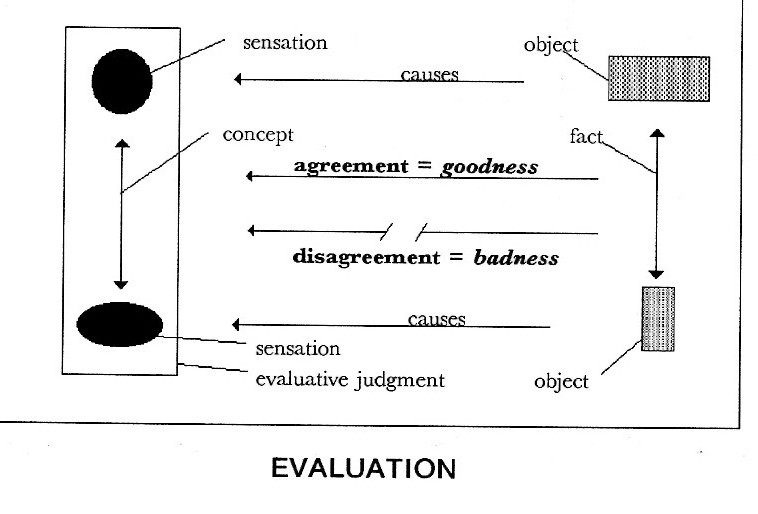

8.5. Goodness and badness

8.5.1. The evaluative judgment

Summary

Exercises

Chapter 9: Freedom

9.1. Different senses of "freedom"

9.2. The controversy

9.3. The evidence

9.3.1. The nature of goodness

9.3.2. The evidence from self-transparency

9.4. Freedom of choice

9.5. The function of choice

Summary

Exercises

Chapter 10: The Human Soul

10.1. Understanding and sensations

10.2. The "faculty" of understanding

10.3. The human soul

10.4. Immortality

10.4.1. Reincarnation?

10.5. The nature of the afterlife

10.6. Human nature as "fallen"

Summary

Exercises

Chapter 11: Self and Person

11.1. Ideals, goals, and purposes

11.2. The self

11.2.1. God and the self

11.2.2. Limits on self-creativity

11.3. Racial and sexual differences

11.4. Natural vocation

11.5. Goals and values

11.6. The person

11.6.1. Rights

11.7. Love

Summary

Exercises

Evidence and Knowledge

This book is an attempt to give you facts about what your life is all about, as far as they can be known scientifically. There will be a lot a book like this can't know about your life, because, as we will see, there is a lot about your life that you can't find out about, because you freely choose to make it what it is. Still, to what extent is there a "you" that you can't do anything about, and to what extent is this "you" flexible, so that you can make it what you want? That is one of the questions we will try to find an answer for.

Second, when I say that the book is about the scientific aspect of your life, I do not mean that what it is going to do is tell you what biology and psychology says about yourself. These are sciences that deal with life, and in fact we will be using a good deal of what they say in our investigation. But they are not the only science that deals with life. Philosophy is a science also, as rigorous a science as physics or biology.

This particular branch of the science of philosophy was originated by Aristotle and called "psychology" (from psyché, meaning "soul"), and is sometimes now called "philosophical psychology" to distinguish it from the experimental science now called "psychology." It used to be also called "philosophy of man," but now this term has yielded to "philosophy of human nature." But in fact, the discipline does not deal simply with human beings, but with all living things, and in particular living bodies, as the title of the book indicates. But aren't all living things living bodies? No, as it turns out. In fact, one of the conclusions we will come to is that your mind will continue to exist after you die; you will live, but no longer as a living body.

But how can I call what this book does "scientific" if it speaks about a life after death? Isn't that religion or something and not science? No. There is as good, scientific, objective evidence that there is a life after death as there is that there once were dinosaurs or that radios emit real radiation.

So even though there are living things that aren't bodies, and even though, as the philosophical investigation of life advanced through the ages after Aristotle, the life of God and that of angels were included within its scope, this book will still confine itself to embodied life, and not do more than mention God and try to show how God can be called "life" based on the definition we come up with from our investigation of observable living things. Since there is no evidence apart from Revelation that there are such things as angels, then philosophically it is pure speculation to talk of them--and so they and their life (if any) are beyond the scope of any philosophical discipline, let alone this book.

1.1.1. Difference from biology and psychology

What we are after is what makes living bodies different from inanimate (non-living) ones, and based on this difference, what the reality of a living body is, and hence what life is. Biologists often say that life can't be defined; and they are right, within the discipline of biology. The reason is that biology investigates the parts of the living body and their function in keeping the body alive, and it is not really part of biology as it is at present constituted to investigate what the living acts imply with respect to the distinctiveness of the living body as such.

Biology investigates living beings from the point of view of how they maintain themselves; philosophy investigates them from the point of view of how their properties reveal the nature of the living body as living.

Philosophy, therefore, can arrive at a definition of life, while this is not something biology can do, because of its orientation. When a biologist defines life, he does so as a philosopher; and his definition is more or less good depending on how good he is as a philosopher, no matter what his knowledge as a biologist may be. Biologists talking about what life is are like skilled drivers talking about how a car works. A really good driver probably has to have some notion of how a car works, but he isn't the person to listen to if you want to know something about auto mechanics.

Where this philosophical discipline differs from psychology is more or less the same. Psychology studies human or animal behavior--behavior caused by consciousness--and considers how consciousness directs the behavior. That is, basically, psychology as a science is concerned with stimuli that get into the brain, and the response that comes out of it. The philosophy of consciousness investigates animal and human behavior insofar as it indicates what consciousness is. Like the biologist, the psychologist is not concerned as such with what consciousness is, but with how it works; the philosopher is concerned with how it works but insofar as this reveals what it is.

Psychology studies conscious behavior from the point of view of how the mind works; philosophy studies conscious behavior from the point of view of what it reveals about what the mind is.

Obviously, these three areas of knowledge, philosophy, biology, and psychology, are complementary, not antagonistic. The philosopher can draw a great deal from what is known in biology and psychology; and the biologist and psychologist can profit from knowing what the philosopher discovers. After all, it's probably easier to find out how something works if you know more clearly what it is that is doing the working.

Before we can actually begin to investigate living bodies from the point of view of the science of philosophy, there are several preliminaries we have to go through.

The first thing we will have to do is overcome two different kinds of prejudice: the prejudice of the ordinary person connected with anyone's talking about "facts" in reference to his own life, and the prejudice of the scientific community toward anyone who wants to claim that philosophy is a science that is just as objective as his own discipline. So what we will first take a look at is what objective knowledge is and what makes knowledge scientific.

But even with that out of the way, we won't be able to get into the investigation proper until we give some conclusions from another branch of philosophy, the Philosophy of Nature, about what bodies are, and what the properties of inanimate bodies are as such. It is a little difficult to see how you could distinguish living from inanimate bodies unless you knew about inanimate bodies.

Mainly, this chapter about bodies will be a look at what energy is and how it behaves. We will discover that energy is measurable, and we need to know what it is about things that allows them to be susceptible to measurement. This is all the more true because there are some scientists (who are not very good philosophers) who think that measurability is a characteristic of things insofar as they are real; and we will see that this is not true.

This investigation into energy will also be important for our purposes, because we will see that living things do not behave the way you would expect energy to behave.

Then we will begin investigating the properties that all living bodies have--the vegetative ones of nutrition, growth, reproduction, and repair--to see if we can find out how living bodies are distinctive. We will discover that living bodies are energy that seems a peculiar sort of energy, and the higher one goes in the scale of life, the more the energy escapes from what makes energy energy. But even at this lowest level, we will be able to come up with a scientific definition of life and of the "soul."

Next we will go on to properties that only some living beings have--properties involving sense consciousness, or conscious reactions to energy--and try to see what this means with respect to what consciousness is, what its relation to energy is, and what this implies about the life of the animal.

After that, we will look at the act that, so far as is known, is exhibited only by human beings--that of thinking--and try to see first, whether thinking is just a complex kind of sensation, or whether it is a distinctively different act that only (as far as we know) human beings possess among the animals.

This will lead us into asking the question of why we think; that is, what "survival value" it has for us as organisms, and we will outline how thinking gives the human being access to the objective facts about the world, instead of merely reacting to it (even reacting consciously). This investigation will allow us to come up with a definition of truth and error, as well as a definition of goodness and badness; we will see how they are different, but how and why they are related.

The fact that we can make mental constructs and use them for evaluation, which we learned about in the distinction between truth and goodness, will lead to how we use this ability to construct possible worlds as a vehicle for changing ourselves and our world and creating it unto our own image and likeness, as it were. And such an activity is choosing.

Since thinking also involves choosing, and choosing implies self-determination, we will then see what human consciousness means with respect to ourselves as persons and our relations with other persons.

[This topic is treated more extensively in Modes of the Finite, Part 1, Section 1.]

As I said in just above, the first thing we have to do is clear away obstacles to the scientific philosophical investigation of your life; and the first of these is the general attitude people have toward facts.

The Disease of the Present Age

The notion that "everyone has a right to his own opinion."

"Well, what's wrong with that?" you say. "What are you, prejudiced or something?" If this is what you are thinking, then you are infected with the disease.

What's wrong with it first of all is that as stated it's meaningless. A right is something that can be violated; it says, "You must not try to stop me from doing X." But how could I prevent you from having an opinion? There is no way I could get into your head to erase it. I might be able to prevent you from expressing it, but not from holding it. The best I can do is try to persuade you that you are mistaken; but if you want to hold onto it in spite of the facts, then there is nothing I can do. In this sense, to say "I have a right to my opinion," means in practice no more than, "I have an opinion."

But obviously people mean more than this by the phrase; and here is where it becomes a disease. It implies that we ought to respect other people's opinions; and what that means is that if I dare to tell you, "That's a false opinion; you have to correct it," then I am somehow being disrespectful to you, because, according to the disease, you have just as much right to your opinion as I do to mine. The person, then, who says, "I'm right and you're wrong," is held to be arrogant, intolerant, and closed-minded.

And this reaction to people who presume to claim to be objectively right (the "intolerant") can sometimes have tangible effects. For instance, the other day the editor of The Way Things Ought To Be, the book by conservative talk-show host Rush Limbaugh, went into a bookstore and found all the copies of the book on the shelf with their back cover facing out. She turned the books around with the front cover in front, and then five men came over and turned the books back the way they were. When the editor asked why they were doing this, they said, "We're performing a service to mankind!" to which she answered, "Oh? Censorship is a service to mankind now?" Of course, they thought that Rush Limbaugh was intolerant, and therefore not to be tolerated.

And that's one of the reasons why we have a disease here. Intolerance must not be tolerated. Why? Because everyone has a right to his own opinion, and therefore those who claim the opposite must not be allowed to hold that opinion.

Note: I am not trying to make out a case that it is a good thing to be intolerant. I am saying that "tolerance" as now misconceived is a disease.

But of course, most of the time people who are "tolerant" don't actually try to suppress what they consider to be intolerance; they simply don't listen to it. "All right," they say. "You think you're right. Go ahead and believe that; you have a right to your opinion. But so do I." They would not try to take Rush Limbaugh off the air, but they are eloquent about how angry he makes them, not because he disagrees with them but because he disagrees and then says that he's right and they are wrong. He's so closed-minded.

So "tolerance" transmogrifies itself into a peculiar form of "open-mindedness," which is just as sick as the "tolerance" itself is.

Modern-day open-mindedness

Since "everyone has a right to his own opinion," therefore I have a right to my opinion, and so do not try to convince me that I am mistaken.

Again, this is a disease because what it is is the opposite of what it says. It is actually closed-mindedness masquerading as open-mindedness. A person infected with it thinks he is open-minded, because he will allow anyone to hold any opinion he wishes; but he is actually closed-minded because he expects everyone to be as "tolerant" as he is--which means that he wants no attack of his own opinions.

Nowadays, we "dialogue," we don't discuss. People who discuss (a) try to correct the other person's mistakes, and (b) try to correct their own based on the information the other person gives them. But "dialogue" means that I let you talk, and you give me equal time. I don't pay any attention to what you are saying, but to "where you are coming from," and I make noises about how interesting and sincere your opinion is, and then I give my opinion just as if you hadn't spoken. The two of us walk away from the dialogue with exactly the same opinions we had before we started, but with the satisfied glow of having "shared our views."

And this form of the disease kills education. Obviously, you can't learn anything unless you are willing to let someone else change your mind and correct your mistakes. But the "right to your own opinion" implies that it is immoral for someone to correct your mistakes, because then he's violating your integrity, showing you disrespect, and all the rest of it; you have a right to your opinion, dammit, and here he is trying to make you give it up and adopt his opinion! Who is he to say that he's right and you're wrong?

You got trouble, my friends, right here in River City, with a capital T, and it stands for "Tolerance."

1.2.1. The source of the infection

To understand this disease better, first we have to see how we got it, because only then can we find a cure for it.

The disease is peculiarly American in its origin. Since many of the original settlers came to America to escape religious persecution, then when we formed a single nation, we wanted to do something to prevent the country from being torn apart by religious wars; and so we refused to establish a national church, and also gave everyone the right to free speech. No religious group was allowed to suppress any other religious group. So far so good; nothing diseased about this.

The problem is that it is very difficult to internalize this non-interference with others' religions without at the same time subscribing to either of two views: (a) that there is nothing factual about any of them, and so none can be called "false" any more than, "Twas brillig and the slithy toves did gyre and gimble in the wabe" is a false statement--or (b) any one of them is as true as any other, so that there is no way to single out one as the "real truth."

But once you adopt either of these views, there is no reason to apply it only to religious matters. Why should only religious people, for instance, be exempt from fighting in a war on conscientious grounds, since many atheists also object to killing people? What is so special about the religious basis of sincerely held opinions that only these opinions should be exempt from interference?

And the result is that, if you are tolerant of various religions either because they are not factual or because no one can say which one is really true, then you are almost bound to extend this tolerance to any sincerely-held opinion, however silly; and this gives us the disease we have today.

But really, now, think for a moment. Suppose someone sincerely believes that the world is flat. Does that mean either that no one can know whether the world really is flat or not, or that the world really is flat for him, while it's really round for everyone else? Why shouldn't you "interfere with his opinion" and try to show him where he's wrong? Or suppose he thinks that he's perfectly safe in having unprotected sex as long as he takes a shower afterward. Does that mean that in fact he'll escape infection because he thinks he will? Does that mean he has a "right to his opinion" and shouldn't be told that he's mistaken?

You can only sustain this "tolerance" if you think that there are no "real facts" and that anybody's idea of things is as good as anybody else's, because no one's ideas are worth a damn. But then what about the idea that "no one's ideas are worth a damn." Obviously, that idea isn't worth a damn either; and so we're back to the disease.

And this is true even in religious matters. Muslims, for instance, believe that Jesus did not really die on the cross, and Christians believe that he did. Now either he did or he didn't. Hence, you can't hold that both the Muslim and the Christian are correct without saying that Jesus both did and did not die on the cross--and that way lies madness. And therefore, if you are going to be "tolerant" in the sense of accepting both as equally valid, you can only do it by saying that neither has any claim to factuality. That is, they can't both be right and be talking about what actually happened; and therefore, if there is such a thing as "religious truth," it doesn't have anything to do with factuality.

The only way, then, to put all religious beliefs on an equal footing is to hold that none of them are really true. So the original non-interference with religion, which was intended to preserve religion from attack, ends up by destroying all religions. This is the religious version of the disease. I will let you hold whatever religious views you want, not because I don't want to see us killing each other, but because your religion is just an emotional quirk you have that is as meaningless as your taste in music.

Well, what is the way out of the dilemma? Must we become like the Serbs and the Muslims in the ruins of Yugoslavia, now killing each other because the other group is the "infidel"? God forbid!

No, but supposing that you have discovered what the facts really are, whether in religious matters or in any other area, it is possible to recognize this, and also to recognize that other people might not have access to the same information, and so might be sincerely mistaken. You don't have to feel guilty and say, "Who am I to claim that I am right and he is wrong?" It isn't who you are, it's what facts you know.

Secondly, it is also possible to realize that people can blind themselves to facts for various reasons; and when people refuse to listen to information you have, you do not have to force them to listen, and can leave them in their ignorance. For instance, I have information that condoms in practice fail about one time in six; so if you have sex twenty times using a condom every time, you have over a 95% chance that your condom will have failed at least once. I tell this to students, and they say, "I don't believe it." I show them how the probability works, and they still say, "That's not true." At that point, I say, "Okay, it's your life."

I'm not admitting that their belief is as good as my knowledge, or that one opinion is as good as another; I'm simply saying that I've done my duty when I have presented evidence to a person. If that person doesn't want to accept it, then that's his problem.

But for those who are infected with the contemporary disease, there is still more:

The Fatal Consequence

Those who hold that "everyone has a right to his own opinion" think that they can make something a fact simply by declaring it to be a fact.

That is, people think that simply believing that something is a fact makes it a fact "for them," even if it's not a fact for anyone else. In other words, facts become things you choose to be true, not things you have to find out. So anyone who tries to tell them that what they believe is not a fact is violating their freedom of choice.

Why do I call this a "fatal consequence"? Consider the boy who thinks he won't get AIDS if he takes a shower, or the one who thinks sex is safe with a condom. You die from this attitude. Yet the disease is epidemic in this form, and we are doing all sorts of things in order to produce certain effects--when in fact what we are doing produces the exact opposite effect. We distribute condoms to kids to reduce pregnancies, when it has been demonstrated again and again that giving condoms to kids increases pregnancies. We increase taxes on the wealthy to stimulate the economy, and (as they always do) the rich move their money into tax shelters which (a) reduces revenue, and (b) slows the economy. We hold bake sales to reduce the federal deficit. A man mutilates himself and says he has "changed his sex," and we call him a woman. A woman pulls apart the child inside her and declares she has "terminated a pregnancy" by removing a "blob of tissue," and you are regarded as a kook if you suggest that she killed her kid. We tax a married couple $ 4500 more than their tax would be if they simply lived together and wonder about the breakdown of the family. I could go on and on.

Why do we do such foolish things? It can only be because of the disease. Whenever you confront someone like this with the facts, he says, "But that's only because we haven't done enough of it," and continues to make things worse, because he wants the results he intends without the unintended side-effect, and because he is "sincere," then you are being intolerant if you point out to him that what he is doing won't work. You aren't "compassionate."

WARNING!

There are no "facts for" someone. A fact is a fact is a fact.

That's a brief look at the disease of our age, then, and something of how much in danger we are unless we can find a cure. But is there one? I said that, supposing we actually know what the facts are, we can still be tolerant and not try to kill or silence others without at the same time getting into the silly position of saying, "They're just as right as I am."

But the problem is, can we actually know what the facts really are? Can we be sure, and if so, how? Maybe these people are right; maybe nobody can find what the real truth is.

The disease, you see, is still doing its dirty work.

We can't spend too much time on this, but I think I need to give you some confidence that there are at least some things that can be known with absolute certainty, and there are things that don't depend on your point of view, but are true for everyone and at all times and in all places. Armed with this confidence, we can then begin looking for evidence, so that we can distinguish knowledge from mere opinion. This will enable us to show basically why science gets us knowledge, and that in turn will show us how we can acquire knowledge philosophically.

If you are wondering whether there is anything at all that can be known for sure without the slightest possibility of being mistaken, consider this:

An Absolutely Certain Fact

There is something

Suppose you doubt whether this is true or not. There's the doubt, and that's something. Suppose you deny that there is something. There's the denial--and that's something. Suppose you question it; there's the question. Suppose you refuse to consider it; there's the refusal. It is not possible for you to be mistaken that there is something, because even the mistake would be something.

DEFINITION: A fact is self-evident when its denial affirms it.

It is called "self"-evident, of course, because it is evidence for itself; your attempt to believe it false proves it to be true. Statements that are self-evident are absolutely certain, because it is not only the case that they aren't false, it is impossible for them to be false.

Not everything declared to be "self-evident," of course, is self-evident. For instance, it is possible to deny "All men are created equal" without somehow affirming it. (Jefferson notwithstanding, this particular "self-evident" proposition is not only not self-evident, it's not even true.)

But since I have shown you a self-evident fact, then there's another fact that's evident through this one:

Corollary I

The human mind is not only capable of reaching truth, it is capable of attaining absolute certainty.

The reason is, of course, if we couldn't reach absolute certainty, then we couldn't know with absolute certainty that there is something--and we do know this.

To clarify things, we now need to give you some technical definitions:

DEFINITIONS: Certainty is a condition in which a person knows that he is not mistaken. Subjective certainty is a conviction of being mistaken without sufficient evidence to back it up. Objective certainty is based on the facts. Certainty is absolute when one has evidence that it is impossible in this case to be mistaken. Certainty is relative when (a) it is theoretically possible to be mistaken, but (b) one has no evidence that one actually is mistaken.

Doubt is the knowledge that one is or might be mistaken. Subjective doubt is the fear, without evidence, that one is mistaken. Objective doubt occurs when one has evidence on both sides of an issue.

A person has knowledge when he is objectively certain. A person has an opinion when (a) there is objective doubt, but (b) the evidence on one side is stronger than the evidence on the other.

So the first phase of the therapy has been taken. It is possible to know at least in some cases what the facts really are; our minds are capable of reaching the truth in such a way that it's impossible for us to be mistaken. This has nothing to do with your choice, notice, because you can choose to deny that there is something, but there's still the choice, and that's something. No choice of yours can make "there is something" be false even for you, because you can't escape being aware that you are making the choice, and hence being aware that there is something.

The second phase of the cure occurs when we look again at "there is something" and ask whether its truth depends on your point of view. Obviously not, because, no matter what point of view you or anyone else takes, there's at least the point of view, and that's something. Hence, there is no point of view from which "there is something" can be false. It is absolutely true: true for everyone, and true in all times and all places (because no matter what time or place, there's at least the time or place, and that's something).

So not only do we know something with absolute certainty, we know that it's not just a "fact for" us, but is a fact for everyone.

Corollary II

Our minds are capable of reaching objective facts, which are facts for everyone.

Let me now state another self-evident fact which is also absolutely true and known with absolute certainty. This particular fact is called a "principle," because it is the source of all our knowledge. It is the fundamental law of human knowledge.

The Principle of Contradiction

What is true is not false in the respect in which it is true. What is is what it is and is not what it isn't.

These are two formulations of the same principle, one the "logical" one (because it deals with truth) and the other the "ontological" one (because it deals with reality). But they say the same thing.

This is shown to be self-evident because if you want to deny it, you have to do so on the basis of thinking that your denial is true and not false. Obviously, if your denial is false, then you haven't really denied the Principle; but if your denial is true and not false, then this means that you recognize that what is true is not false in the respect in which it is true. But that's what the Principle says.

Let me give another clarifying definition:

DEFINITION: A contradiction is a statement that is both true and false.

Obviously, statements can contradict themselves (e.g. "I am not now writing the words I am now writing.") but facts can't. That is, I can't in fact not be writing what I am writing, because if I'm not writing it, then I ain't writing it.

Notice that some things that at first blush look like contradictions aren't: for example, "I am not now writing what I am writing," if I understand "now" to mean in the one case the moment where I am pausing to think of how to phrase the sentence, and in the other the whole period during which I am engaged in this occupation. In that case, the statement is not false in the respect in which it is true, but is false in one respect and true in the other.

In any case, another way of stating the Principle of Contradiction is "There are no real contradictions."

Now we can define a term we have been using up to this point:

DEFINITION: The evidence for something is some known fact which would be contradicted by the falseness of what it is evidence for.

For instance, your evidence for me (the writer of these words you are reading) is (a) that you see the words, and know that they are facts, and (b) you know that pages don't spontaneously grow words, and so they wouldn't be there unless some writer had put them there. So the words would be a contradiction without the writer. Hence, since there are no contradictions, the writer must exist or at least have existed.

And this leads us to science.

Scientists are fond of saying that they don't waste time in speculations, and simply confine themselves to the observable data. But no one ever observed an electron or radio waves, the chemical bond, a gene, the unconscious mind, or thousands of other things the scientists talk about--and no one ever will, because these objects are in principle unobservable. They tend to say that philosophy is pure speculation, and so one philosophical theory is as good as another, while science, confining itself to "the facts" and to observable data, and asking the question "how" rather than "why," gets at whatever knowledge we can hope to have about things.

But this isn't quite what is going on. Here is what science is:

DEFINITION: Science is the systematic attempt to know facts that are not directly in evidence.

Science is not simply a mass of observations; it uses these observations either (1) to discover laws, which are invariant modes of acting, so that future events (which obviously are not directly in evidence) can be predicted, or (2) to learn the structure behind what is acting in the observed way--the structure which accounts for its behavior.

Thus, for example, the Law of Falling Bodies says that objects dropped from above the earth all fall to the ground at the rate of 32 feet per second per second, regardless of their weight, if you eliminate factors like air resistance. Thus, you know that this ten pound weight will fall at that rate of acceleration if you drop it. Newton's Theory of Universal Gravitation says that what accounts for this is that there is a definite (but unobservable) force attracting bodies to each other, whose quantity happens to be such that the acceleration is always the same.(1)

Now while it is true that there are systems of philosophy that don't deserve to be called any more than "pure speculation" in that pejorative sense scientists use, there are other systems that are just as scientific as any scientific theory--and, for that matter, there are supposedly scientific "descriptions" that for sheer speculativeness would put the wildest philosophy to shame. Once when I was an editorial assistant for Sky and Telescope magazine (a semi-popular astronomical journal) I had to review an article in, as I recall, Science, that busied itself with "describing" what the constitution of any extra-terrestrial intelligent life form would have to be--and the conclusion was that he would have to look just like us.

What is the difference between speculative meanderings and scientific knowledge?

DEFINITION: Speculation is finding a possible explanation for an apparently contradictory set of facts.

The bad sense of "speculation" is simply dreaming up a state of affairs that is not internally contradictory, like what extraterrestrial beings are like. The idea is that, since what contradicts itself is impossible, then it is assumed that if something does not contradict itself, it is therefore possible; and if it's possible, then, well, it just might exist, after all. Who can tell?

But this comes very close to the disease we just got cured of. The fact that you can't prove something doesn't exist is no evidence that it does exist. On the basis of this kind of speculation, you have no reason for saying that what you are talking about exists at all. It is this kind of speculation which is a waste of time.

But the kind of speculation I defined just above is actually the second and third steps in a scientific investigation (the first is finding the set of facts that don't make sense by themselves--or that need explaining). The second step is the construction of a possible explanation, (the speculation) and the third is seeing if (a) this explanation is internally consistent--doesn't contradict itself--and (b) if it actually does make sense out of the facts you discovered.

But if you stop there, you are still engaged in speculation and not science. The reason is that there are an infinity of possible internally consistent explanations for any given set of puzzling facts--and of course only one of these possible explanations is the one that actually exists and does the explaining. Science is not interested in what might be the case, but with what (so far as can be known) is the case.

It's not our task here to go into a detailed investigation of science. I just want to give you enough information so that you can see how it works, and why it is able to give us facts that we don't directly observe.

DEFINITION: An effect is a set of facts that need an explanation. It is a set of facts which, taken by themselves, contradict each other. (I.e. the effect is a situation that "doesn't make sense" by itself.)

Obviously, then, effects can't exist by themselves (because then they'd be contradictions, and there aren't any contradictions. You put coins in your pocket in the morning and reach in to get them at noon, and they're not there; but coins don't walk out of pockets. But they can't be both there and not there; and so there's got to be an explanation: somehow, they got removed from your pocket.

DEFINITION: An explanation is a possible state of affairs which, if true, would render the effect not a contradiction (i.e. would "make sense out of" the effect).

Here's where speculation comes in. You try to figure out how the coins could have got out of your pocket.

DEFINITION: A cause is an explanation that is also a fact. (I.e. it is the true explanation: the fact that actually does make sense out of the effect.)

An explanation, then, is a possible cause. Speculation leaves us with possible causes; science goes the step farther and tries to discover which of the possible causes is the real one.

DEFINITION: A theory is an internally consistent explanation of an effect which "fits the facts" to be explained.

That is, it leaves none of the originally observed facts still a contradiction. For instance, if you find a hole in your pocket, you have an explanation of how the coins got out: they fell through the hole. But if the hole is dime-sized and you had quarters in your pocket, the quarters would still be there--and so this explanation doesn't work. Both scientific theories and speculative theories are theories. But science tries to prove its theories.

Not to make a long story here, science does this basically by making predictions from the proposed explanations, once they have been discovered to be internally consistent and to "fit the facts" they are supposed to explain.

DEFINITION: A prediction is a state of affairs that logically follows from the explanation in question; it must be a fact if the explanation is the true one.

Suppose we take Galileo's observation that all bodies fall, due to gravity, at the same rate of acceleration. But we find that in fact a ball of cotton does not really accelerate as fast as a ball of lead when you drop them. We then construct the theory that it is air resistance, not gravity, which explains the difference.

A prediction from this theory would be that in an air-free condition, both lead and cotton would fall at the same rate. If air resistance explains why they normally don't, this prediction would have to be a fact.

Science then tests these predictions to find out if they are facts; and it eliminates those theories that turn out not to be "verified." Thus, when Neil Armstrong dropped a hammer and a feather on the moon (where there is no air), both hit the ground at the same time--which verifies the theory.

Notice that the verification of this theory automatically falsifies the theory that heavy bodies fall faster than light ones because they are heavier.

If, of course, the theory predicts something that is not actually a fact, then this explanation cannot be the cause (because if it is a fact, the prediction, by the logic of the situation must also be a fact). Hence, the theory is discarded and a new theory developed that does not have this difficulty. Thus, for instance, Newton's Theory of Universal Gravitation predicted that the orbit of Mercury would be slightly different from what it was actually observed to be early in this century when we developed very sophisticated instruments. It was that failure which made the theory yield to Einstein's General Relativity Theory.

Sometimes the predictions can pretty well eliminate other theories; sometimes they can only indicate which theory is more likely to be the true one. But the point is that science has more reason to be considered factual than pure speculation, however internally consistent the speculation might be.

Scientific facts, then, are not self-evident, but evident through the observations they are explanations of. But since the observed data contradict themselves when taken by themselves, we know that there must be some explanation; and any reasonable person will accept as factual a scientific theory unless evidence presents itself that the theory is false. The fact that it could be false doesn't mean that you don't have knowledge and even certainty, as we saw above.

HISTORICAL SKETCH

Philosophy tends to get into a period of disease like our own when brilliant thinkers devise internally consistent views of the world, but the different views contradict each other. The first two great philosophers to do this were Heraclitus (c. 530 B. C.) and Parmenides (c. 500).

Protagoras, (c. 450 B. C.) was the first relativist; he held that "the human being is the criterion for everything," or in other words, it all depends on your point of view. He was rather soundly refuted by Plato (c. 425), who developed a coherent theory that combined Heraclitus and Parmenides; but he had a student, Aristotle (c. 350), who contradicted his view with another brilliant theory.

This led to the Skeptics, prevalent about the time of Jesus, who held that it was not possible to reach certainty. They were refuted by St. Augustine (c. 400 A. D.), and Christian philosophy reigned through the Middle Ages.

But with Galileo, in the 1500's, new observations came to light which seemed to refute the philosophical base of Christian thought, and Michel Montaigne (c. 1575) reintroduced a kind of skeptical relativism, on the grounds that no one really knew anything, and so you might as well be a Christian. This was refuted by René Descartes, (c. 1600) who started philosophy off on a new direction by his discovering "I think, therefore I am" in his attempt to doubt everything doubtable. He thought he could use mathematical method and deduce the truth about the world from his original, absolutely certain insight.

Several other people developed internally consistent theories, however, and the theories again contradicted each other; and David Hume (c. 1750) once again developed a skeptical view that we can't really know anything except what we observed; predictions are just hopes that what happened in the past will happen again. However, Immanuel Kant (c. 1800) showed how Hume's objections against science's truth could be answered; and science at least seemed on solid ground, even though there were philosophical spinoffs from Kant that again developed contradictory theories.

Finally, science itself, at the turn of this century, discovered that things that it had held to be unassailable truths, like the Theory of Gravitation, were false; and quantum mechanics seemed to indicate that the very act of observing something changed what you were observing. And this is the source of our present unease about truth.

This book deals with embodied life. Its science is different from biology in that biology studies how living beings live, and philosophy what their properties reveal about their nature as living; it differs from psychology in that psychology studies behavior to see how the mind works and philosophy studies behavior to see what the mind is.

Serious investigation is hampered by the disease of the present age, whose symptom is the statement, "Everyone has a right to his own opinion." This can't, strictly speaking, be a right, because there is no way to prevent a person from having an opinion if he wants to, and so the "right" cannot be violated. But it supposes that anyone who claims that another person is objectively wrong is showing disrespect for the other person, and is intolerant.

But people who have this kind of "tolerance" are not really open-minded, because what they really want is not to have anyone else challenge their opinions; and this kills discussion and learning.

The disease arises from religious tolerance; instead of not fighting over religious truth, the corrupt version of "tolerance" refuses to recognize that the truth can be discovered; and it is not long before this attitude carries over to any sincerely held opinion. Its fatal consequence is that people think they can make something a fact simply by declaring it to be a fact. When put into practice, this attitude has disastrous consequences. The reason is that a fact is a fact; there are no "facts for" a given person.

The cure comes in recognizing that we can know at least something with absolute certainty: that there is something. The attempt to deny this proves it to be true. And we can also know that there are things which are true for everyone, and do not depend on one's point of view: from any point of view, "There is something" cannot be false. We also know the Principle of Contradiction: that what is true is not false in the respect in which it is true. These two propositions are self-evident.

The evidence for something is some known fact which is contradicted by the falseness of what it is evidence for. Science is the systematic attempt to know facts that are not directly in evidence, by observing effects: sets of facts that would be a contradiction unless something unobserved is a fact. The cause is the unobserved fact that saves the observed situation from being a contradiction; and an explanation is a possible cause.

Speculation tries to find the explanation of observed effects; this explanation must be consistent (not self-contradictory) and leave no facts unexplained. Science goes beyond mere speculation by predicting what else must be true if the explanation is the cause, and then checking to see if that prediction actually is a fact. If not, the theory cannot be true, and the explanation does not actually get at the cause of the effect. It is then discarded and another theory is developed.

Exercises and questions for discussion

1. It would seem that, if we've ever thought we knew something for certain and later found out we were mistaken, we can never be sure that this won't happen again. So no matter what we think we know, we can't really say we know it with absolute certainty. How would you answer this?

2. How can philosophy pretend to get at what the facts are if it doesn't take measurements? That shows that it's just sloppy thinking, and so can't compare to science, which is exact.

3. If you've proved something to a person, can he still disagree with you? Could he disagree with you and be right?

4. If you are going to discuss something with a person, how do you start? You can't just make an assertion that he will simply deny. How do you get into a position where you'll make progress?

5. What do you say to people who claim that since the Theory of Evolution, for instance, is "just a theory," they don't have to believe it?

6. Do religions tell us what is factual? If so, how could we know which one is true (if any) and which one false?

1. Actually, if you want to be technical about it, it has since been discovered that the force Newton thought existed doesn't actually exist. What is now thought to account for falling bodies is a warping of space-time in the presence of massive objects.

Bodies

If, as we said in Chapter 1, we are going to talk about embodied life, or living bodies, then we have to know what a body is first, before we go on to the distinctive characteristics of a body as living.

The study of what a body is and what characteristics it has as such is extremely complex, and could easily take several volumes to do justice to. Here we can do no more than skim briefly over a vast area of philosophy, and instead of presenting evidence and discussing contrary positions, we will just give the conclusions that seem most reasonable, based on the examinations that have gone on through the centuries.

WARNING!

This chapter is going to consist mainly of definitions of terms you will need to know throughout the book. Memorize them now, or you will be lost in later chapters.

Take this warning to heart. Many of the terms will be familiar ones: body, existence, activity, energy, process, purpose, and so on. But we are doing a scientific investigation here, and the terms have a very precise and technical significance. And even through the technical meaning may be somewhat similar to their ordinary use, if you don't have the technical sense in mind as you read later chapters, the ordinary meaning may seriously mislead you.

Let us begin by a definition of our main topic, and then try to make its parts clear:

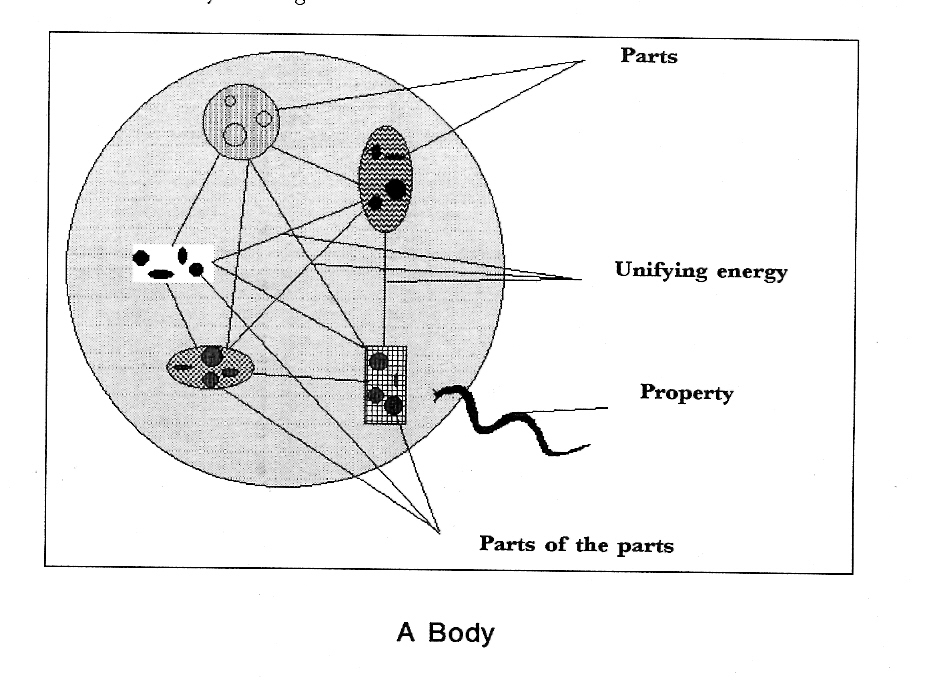

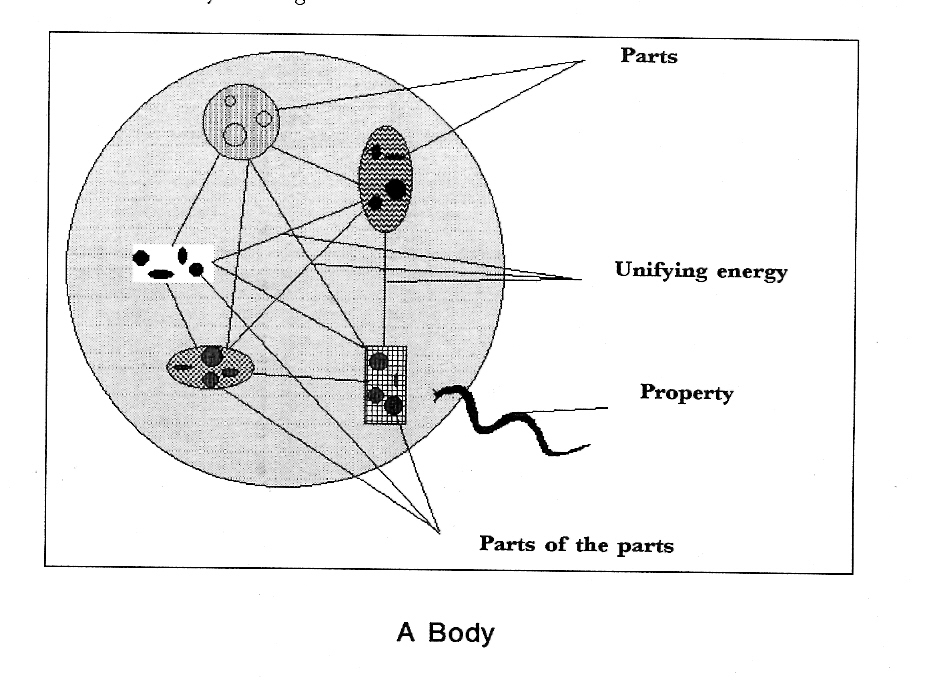

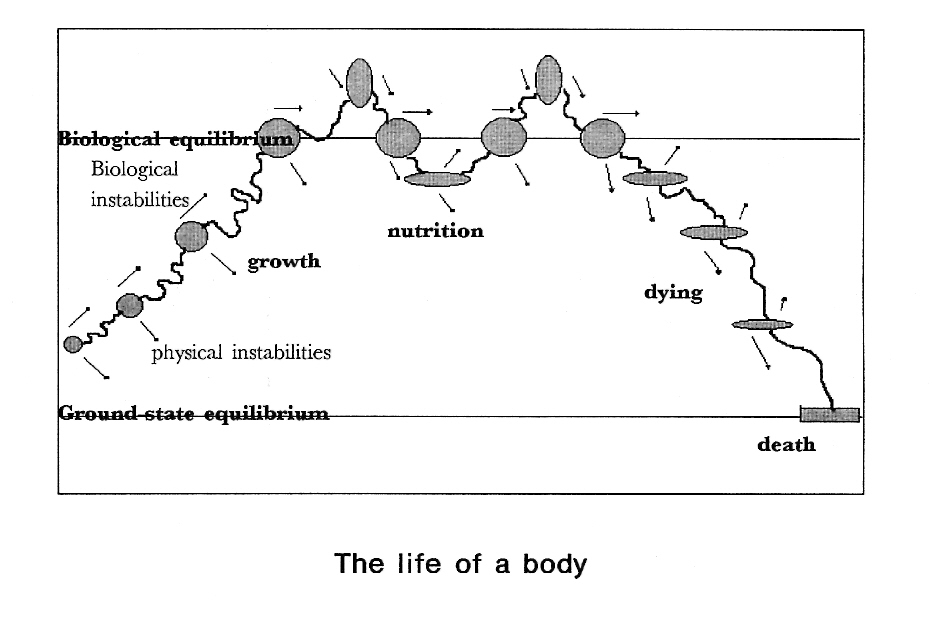

DEFINITION: A body is a real object consisting of various forms of energy tightly held together by a another form of energy.

In other words, a body is made up of energy, and so our first task will be to see what the reality of energy is.

[This topic is discussed at much greater length in Modes of the Finite, Part 1, Sections 3 and 4.]

In physics, energy is called "the capacity for doing work," and "work" is defined as "motion over a distance." This is a good example of the different orientations of philosophy and the empirical sciences. Physics is interested in discovering how much energy is used up in doing some work (i.e. in measuring it), and so is not concerned with what it is that does the work except as "the whatever-it-is that does work." In philosophy, we try to find out what it is that is being referred to by this indirect definition.

Even this road is a long and twisting one, and to make a long story short, it turns out that what physics is talking about is any sort of reality, provided that the reality in question is measurable.

So as a preliminary definition, we can say that energy is measurable reality.

Note, by the way, that it is a pure dogma of physical science, unsupported by any evidence, that every reality is measurable. As a matter of fact, we will discover evidence that certain undoubted realities cannot be measurable (or they would contradict themselves). This dogma is false.

But then what is reality?

It might be thought at first blush that anything we can talk about, or especially anything we can be conscious of, is a reality; but obviously this is not true. We can imagine and dream; and the objects of our dreams and imaginings are not real (at least as we imagine them).

But then if we notice the difference between imagining and experiencing what is real, we observe that in imagining, we are producing the images by ourselves (we are acting spontaneously, without responding to any information coming into us), and in experiencing the real world, we recognize that we are reacting to something.

Thus, if we say that something is real or exists, we say so on the basis of the fact that we are reacting to it directly or indirectly; and so it is either acting on us, or acting on something that is acting on us (which action on us is an effect, arguing to the existence--activity--of the cause). Anything that wasn't acting in any way couldn't be providing any information for us to know it, and so could not be known as real or existing.

From this we can say the following:

DEFINITION: Existence is activity. To be is to do.

Now this is "activity" in its broadest possible sense: doing anything at all. Even "being passive" is a kind of activity, since it is really reacting to some other activity. You don't have to do something to something else to be active or exist either; thinking is an activity, for example. The act of thinking is an "existence" of you (an activity), even though it stays inside you.

Note that existence does not depend on your knowledge of it; your knowledge of it depends on it. A thing can exist without acting on you (or anything else). In this case, you won't know that it exists, even though it does exist. But you can't know that something exists unless it is acting on you, either directly or indirectly.

Now activity is not simple; it turns out that all activities except one (the one called God) are limited or finite activities.

DEFINITION: Absolutely unlimited activity (i.e. activity that is neither of a certain type nor of a definite amount, but is infinite both in form and quantity) is called God.

There is only one possible such "pure activity," because if there were two different ones, then what made one differ from the other would be a limitation: a form of activity.

DEFINITION: The form of activity (or existence) is the limitation of activity to being only one kind of activity.

That is, it is the fact that the act in question is nothing more than the particular type of activity in question (e.g., thinking, seeing, heat, electricity).

Note that the form of activity is not something added to the activity (because this form of activity is less than what it would be if it were just activity). Hence, the form is not a reality in itself at all. How could it be? If it were a reality, it would have to be an activity, and then activity would be limited by itself. So the form is simply a way of considering an act that is not all there is to activity.

DEFINITION: Spiritual activity is activity which is either absolutely unlimited (God) or limited only in form and not further limited in quantity.

Spiritual activity is infinite with respect to quantity, but not necessarily absolutely infinite (or unlimited). The thought that "there is something," for instance, does not have any degree to it; it is not measurable. But it is clearly different from the thought that you are reading this page. Each is a different form of activity, but neither is greater or less than the other. We will establish later that thinking is in fact a spiritual activity and is not measurable.

DEFINITION: The quantity of a form of activity is the limitation of a given form of activity to being only a certain amount of this form of existence.

That is, the quantity is the fact that there is only this much of the form of activity in question (e.g., the temperature of heat, the charge of an electrical field).

The quantity of an activity makes that form of activity measurable.

Note several facts here:

1. The quantity, like the form, is not something in itself; it is merely a limit. In fact, the quantity is the limit of the limit called the "form," and so in itself it is doubly nonexistent. Think of the temperature of heat. It is clearly not something that you add to heat to make only this much of it; it is just that the heat "stops," as it were, at this degree.

2. It is not necessary for existence (or activity) to have either of these limitations. Things can be real without being measurable, and even without being a specific kind of thing.

3. If a given activity has quantity, it is then measurable, because numbers can be applied to it. Spiritual activities are not measurable.

[This topic is discussed at great length in Modes of the Finite, Part 2.]

I said in introducing this chapter that energy is any sort of reality that is measurable. Well, reality is what exists, and existence is activity; and we now know that quantity is the aspect of some activities which allows them to be measured; and so it follows that:

DEFINITION: Energy is any form of activity which is limited in quantity.

Note that energy is not the quantity (the limitation). The quantity is the energy's amount or degree; the energy is the act which is limited to this degree. But to be called "energy," activity has to have a quantity. There's nothing mysterious about this; it's just that we don't call spiritual acts "energy," because we reserve "energy" for acts that are measurable.

Energy is a "catch-all" name. There is not some special thing called "energy"; energy refers to any activity, provided the activity is measurable (is limited quantitatively). Thus, heat is energy, light is energy, mass is energy, electricity is energy. All these are forms of energy (because they are forms of [measurable] activity).

In other words, energy is non-spiritual activity.

Thinking, as we will see, is not a form of energy. It is like energy in that it is a form of activity; but it is unlike energy in that it has no quantity and therefore cannot be measured. "How much" thinking is going on is a meaningless question.

The reason energy is called "the capacity for doing work" is, of course, that you can't move something (or do something analogous) without being active, whatever form the activity happens to take. And energy, being limited quantitatively, is used up by doing work, and so you can measure how much energy did the work by measuring the work done.

Spiritual acts, by the way, are not "used up" by doing things, and so the "work" done by them does not indicate "how much" of them there is. When a choice of yours pushes around some electrical impulses in your brain, this does not take some activity away from the choice-act; the choice-act, being only a kind of activity without a quantity cannot lose "some" of itself; it either is or it isn't; it admits of no degrees by which it could be "less."

HISTORICAL SKETCH

Plato (c. 400 B.C.) was the first philosopher to notice the spiritual as not bound by the "conditions of space and time" (which we have learned in the centuries since means measurability); and he spoke of "Aspects" (later translated "forms") which were the "realities" of the observable things we see. He thought that the "form" of something like light was a spiritual thing which had individual "lights" sharing in it more or less imperfectly.

Aristotle (Plato's pupil, c. 350 B.C.) discovered that what Plato called "form" was really "activity," (for which he invented the word that we took over as "energy"); but he thought the acts were acts of some "stuff" or "matter" things were "made of." The act made the matter a kind of something, and the matter made the act an individual; he thought of the form as limiting the matter, and the matter in a different sense as limiting the form.

Plotinus (c. A.D. 250) noticed that the forms were limitations, but not of matter; matter was the limitation of form. The form was a limitation of something that could not really be named, but which he referred to as The One, and thought of as God. With Plotinus, however, the notion of activity was more or less lost; reality was a kind of static something-or- other.

St. Thomas Aquinas (c. 1250) got back the Aristotelian notion of "activity" or "activeness", and was the one who saw that God was pure, unlimited Activity, that the "form" was nothing but a limitation of activity and "matter" was a limitation of "form." He called limitation "potency" for reasons we don't have to go into. St. Thomas also saw a connection between "matter" and "quantity."

The whole of this investigation was stopped, however, shortly after the Renaissance, when René Descartes (c. 1625) began approaching "reality" from the point of view of consciousness. No one, right up to the twentieth century, paid any significant attention to the distinction between imagining (creating acts of consciousness) and perceiving (having reactive acts); and so "reality" philosophically wallowed in the morass of "the object of consciousness," and philosophers spoke of "the real world" as if it were just a fancy type of imaginary world.

It is only now that we have got round the problems of knowledge initiated by Descartes and "rediscovered" what any five-year-old knows, that there really is a real world out there, that we can resume a scientific approach to the study of reality.

During the Renaissance, Galileo (c. 1600) started the empirical sciences moving ahead by stressing measurement (which he thought got around problems of knowledge), and so discoveries were made about energy, and all sorts of "forms" were found to have their own quantities.

These advances, however, went along independently of the progress--there was progress--in philosophical investigations; and it is only now that we can begin to fit the two together again. Interestingly enough, however, science is now, in the deeper levels of physics, running up against the problem of knowledge which it avoided for four hundred years. There are certain experiments which seem to indicate that if you decide to measure the act one way, it is one kind of thing (and is in two places at once), whereas if you decide to measure it a different way, it is a different kind of thing (and in only one of the two places it is in). Physics now needs the results of the philosophy of knowledge, just as philosophy needs the results of the sciences, before both can catch up to where each should be.

We saw at the beginning of this chapter that bodies are bundles of energy, united by a special form of energy. So now we can say that bodies are bundles of different forms of activity, each of which has its own quantity; and all these forms of energy are held together by a form of activity which has its own quantity.

Bodies are special cases of systems. Any system is various forms of energy (or sub-bundles of subsystems of various forms of energy) held together by a unifying energy. If you refer back to the definition of "body" earlier, you will see that this means that a body is a tightly unified system. What then is the difference between the two?

A body is a system which is so tightly unified that it behaves (acts) more like a single unit than a number of interconnected objects.

There is something mysterious here. Even though the body is many activities, they are interconnected in such a way that it acts like one reality (activity) in some sense. Thus, if you hit someone with your hand, it is you, first and foremost, that did this act. A body exists primarily as one act, secondarily as many acts.

This one-and-not-one aspect is due to the body's finiteness; but it is not our point here to investigate this further, so let us go on.

In general, the dividing-line between a system and a body is somewhat arbitrarily drawn. If the object in question has properties that are different from the properties of the individual parts, then we tend to call it a single body; if it doesn't do anything much that can't be explained by a simple sum of the parts, then we call it a system.

The extremes are pretty obvious. The solar system is a system, even though it is held together by the sun's gravitational field. An animal is a body, even though it has many different organs. In the case of the solar system, the planets are pretty largely independent of one another; in the animal, the parts exist for their function in the animal as a whole.

But is a stick a body or a system of bodies (the molecules of the wood)? Here we are in a borderline case, and it depends on how you want to look at it. In ordinary usage, we think of the stick as one thing; but when you break it in two, nothing much has happened to it--whereas if you "break" a molecule in two, you get two entirely different substances.

But the problem of when something "deserves" to be called a body instead of a system is not something we have to worry about. What we are concerned with is what a body is (or what makes a body a body, if you will). And it seems that a body, as opposed to a system, is just a system whose unification is what is most significant about it.

This unification, of course, is brought about by some form of energy, as I said. It is this unifying energy which gives the distinctive structure to the body, whose form makes it the kind of body which it is, and whose quantity gives the body its fundamental energy level as a whole.

DEFINITION: The unifying energy of the body is the energy connecting the parts, making them behave together as a distinctive unit.

This unifying energy it is basically the interaction of the parts as they "act together as one." It is simply the energy unifying the body; the energy connecting the parts; it is how the body is held together, so to speak. In an atom, for instance, the unifying energy is the internal electrical field connecting the electrons and the nucleus.

Since this unifying activity is in fact a form of energy, then obviously it has a form and a quantity. The form of the unifying energy is the way the parts are interacting; its quantity is the degree of that interaction of the parts.

Note that it is the form of the unifying energy of a body that makes the body the particular kind of body that it is. Bodies do not differ in kind by reason of the parts that make them up, but by reason of how those parts are arranged or "structured" (in other words, what they are doing to each other). A human being differs from a lion, say, not in the chemicals that make up his body (the parts), but in the fact that these parts have different internal relationships as they make up the organs which in turn make up the body. And these "internal relationships" are nothing but the particular form of unifying energy. The structure of a body is something dynamic, not static; it is the way the parts are behaving toward each other.

Practical consequence 1

A body is a human body, not because it has certain parts, but because the parts are interacting in a human way. Any body with this type of interaction among the parts is a human body, whether it "looks" human or not.

Thus, Black people are human, though they look different from White people, because (as can be seen from the fact that Blacks and Whites can marry and have children with the characteristics of both) their bodies are organized in the same way. It is also clear that the bodies of fetuses are organized in the same way as the same body is organized after birth; why else does the body have organs (such as eyes or hands) that make no sense to his life inside the uterus? Hence, human fetuses and even human embryos are in fact human beings.(1)

Note secondly that, since the unifying energy's job is to knit the parts together into a unit, the unifying energy is not directly observable from outside the body. You have to argue to the fact that it is there because of the observable behavior of the body. Hence, no one will ever get an instrument which will be able to measure whether Jews or Japanese or fetuses are human, because if such an instrument were introduced into the body to detect the unifying energy, the unifying energy would detect it and refuse to interact with it; it would just be another body inside the body in question, and would be rejected as a part of the body.

But this doesn't mean we can't know what kind of unifying energy a body has; its observable activities will reveal it.

Note thirdly that the quantity of the unifying energy accounts for the differences in bodies of the same type. That is, you and I differ as humans in that your unifying energy (which is the same kind as mine) has a different degree from mine; our bodies exist at different energy-levels.

Note fourthly that the quantity of the unifying energy determines the energy-level of the body as a whole. Just as the form of the unifying energy determines the kind of body, so its quantity determines the basic amount of energy that is in the body as a whole.

Practical Consequence 2

Since "equal" is a quantitative term, it follows from what was said above that no two human beings are created equal.

We are all (qualitatively) the same (human); but each of us is more or less human than our neighbor. This is obvious. We will see shortly that the body reveals itself in its behavior; and some of us can do a great many human acts and do them very energetically, and others of us can only do a few. No two of us exist at exactly the same energy-level of humanity.

Before you get nervous at this, let me note that human rights depend on the form of the unifying energy, not its quantity. You have a right to life and liberty because you are a human being, not because you are a well-developed human being. And if you should be knocked out and be unconscious and not able to exercise any of your human behavior except breathing and heartbeat and so on, you would still be a human being, and would still possess all your human rights.

In that sense, each of us is "just as much a human being" as any other human being. But in the strict sense, a child is not as much of a human being as he is when he is an adult, and his body has reached its proper energy-level; and even when an adult, he may very well be not as great a human being as someone more genetically gifted.

THEOLOGICAL NOTE

Since the form of the unifying energy) makes the body the kind of body which it is, then this would allow us to interpret something that Catholics believe in the following way: When the priest, in the person of Jesus, says of bread, "This is my body," and of wine, "This is my blood," then Jesus himself (by his divine power) takes over the function of uniting the elements of the bread, (probably mimicking the unifying energy). Hence, the "bread" is not really bread any more, because its unifying energy is not its own but Jesus' activity--and so it really is Jesus.

Since there is only one Jesus, then if he does this to many pieces of bread, then they are all one and the same body (because they are united by one and the same "unifying activity"--Jesus' act), and are not "many Jesuses" any more than the many cells of a normal body are many bodies.

Of course, there is no evidence apart from Revelation that Jesus does this. The point is that it is not unthinkable that if he is divine, he could do it, and if he does do it, then the bread really ceases to be bread, even though all the elements and properties are there, and is really Jesus.

DEFINITION: Parts are the subunits of a body, each of which has its own form of organization; but the parts are all subordinate to and under the dominance of the energy unifying the body as a whole (i.e., the unifying energy).

In a system, the "parts" are the primary aspect; but then they are called "elements of the system" rather than "parts."

Since a body is many parts cooperating, and nature as it were, to form a complex unity, it would not be surprising to find that the unit itself acts in complex ways.

DEFINITION: Properties are the way a body acts because it has both (a) a certain unifying energy and (b) a definite set of parts.

DEFINITION: The nature of a body is the body looked on as the "power" to perform the acts which are its properties.

Thus, for instance, it is the "nature" of hydrogen to combine with oxygen to form water, or to have a certain spectrum when excited, or to be a gas at room temperature, to be colorless, to have a certain mass, etc. That is, it is because the hydrogen molecule consists of two hydrogen atoms (the parts, having their own internal structure--their own "sub"-unifying energy) united by a covalent bond (the unifying energy of the molecule as such) that it acts in certain ways in response to various forms of energy.

Properties, then, are basically distinctive energies of a body, which it performs (all energies are acts, remember) in various circumstances; properties reveal what is acting, and this is why it is useful to speak of the "nature" of things as revealed by their acts.

Note that properties are not parts. The hardness of a piece of wood, its size,

shape, color, are in fact behaviors of the wood in response to energy around it; its parts are the atoms that make it up.

Note that properties are not parts. The hardness of a piece of wood, its size,

shape, color, are in fact behaviors of the wood in response to energy around it; its parts are the atoms that make it up.

All of what we think of as "characteristics" of something are in fact acts it performs; behaviors of it. These are its properties. The act you are now performing as you read this (your reading) is a property of you as this individual. It is an act which reveals what you are--your individual nature (something which can do this because of the way these parts are organized).

We usually restrict the term "behavior" to properties of animals, because these properties are controlled by the consciousness of the animal. Still, it is useful to call all properties "behaviors," since this stresses the idea that the property is not something static, but what the body is doing.

HISTORICAL SKETCH

Aristotle (350 B.C.) initiated the study of what we are talking about. He spoke of the "reality" of something as opposed to its "accompaniments," and these words were mistranslated into Latin as "substance" and "accidents." The "reality" corresponds either to what I have called the "unifying energy" or to the body as a whole, and the "accompaniments" are what I called the "properties." He referred to the "reality" (the "substance") as the "primary activity" and the "accompaniments" as "secondary acts." He also defined "nature" almost exactly as I have done just above.

In the Middle Ages, "accidents" were defined as "that which exists in another," meaning that they were the existence (the act) of something (the "substance") rather than realities in their own right--as color is always the color of some body. The "substance" was then defined as "that which exists in itself," meaning that it wasn't an act of something else.

There was a good deal of confusion about whether the "substance" was the whole object or the unifying activity of the object, because the word was used in both senses. The "substantial form" was the form of unifying activity and also the form of the thing as a whole (which, of course, it is in my system also--but in those days, it was not clearly seen that they were not the same in concept). It looked as if the "substance" united the "accidents," when in fact it unites the parts. In my terminology, there was confusion between the parts and the whole and the body and its properties. (This was added to by the fact that the atomic theory of bodies was not developed, and they were considered to consist of a continuous mass of stuff.)

Descartes (1625), who approached reality through thought, probably did more damage to the investigation of reality by his misunderstanding of "substance" than anyone else has ever done before or since. He took the definition, and instead of trying to discover what effect it was intended to explain, he simply said "substance is what exists in itself (or is independent)" and concluded that if you had two "clear and distinct ideas," (i.e. concepts that were, among other things, independent of each other), then they referred to two different "substances." Since "thought" was different from "extension" (spreading out in space), then it followed that a mind was a different substance from a body; and therefore the human being was not one thing, but two--or rather, a human being is a mind, but with the peculiarity of being inside this other object called a body. So we "have" bodies the way we "have" clothes.

Baruch Spinoza (1650), who came shortly after Descartes, took his notion of "substance" as "independent" and said that, since we all depend on God, there is really only one "substance," and we are all "modes" (modifications) of Him. (You can see how far away from the original notion of how the parts of a multiple unit are unified we have come.)

Gottfried von Leibniz (1670), about a century before the founding of our nation, interpreted "substance-independent" as meaning that there are many "substances," but they are all "independent" of each other; and each "substance" actively produces all of the events of its life from within it, without either acting on or being acted on from anything outside--except that the "substance of substances" (God) picks out the set of "substances" that fit together, so that as John performs the act of speaking-to-Frank (without actually acting on him), Frank happens to be performing the act of listening-to-John (sort of like a dream, without actually being acted on by John's voice). This "preestablished harmony" makes everything work out just as if substances acted on each other.