In Memoriam: George A. Blair (1934-2013)

George A. Blair was born in Watertown, Mass. in 1934. His father was a legally blind schoolteacher who worked as a piano tuner after the Great Depression; his mother was a caretaker at Perkins Institution for the Blind, who was born in Prince Edward Island, Canada. He had one older brother, Roy. In 1947, at age 13, he sat for an award-winning portrait painting by the artist Mary Rosamond Coolidge.

He entered the Jesuit novitiate and attended Shadowbrook Jesuit Seminary in Stockbridge, Mass., where he watched as it burned to the ground in 1956.

After leaving the Jesuits, he studied at Boston College, receiving his A.B. and M.A. in philosophy in 1958 and 1959 respectively. He also earned a Ph.L. in philosophy from Weston College, Weston, Mass. in 1959, and served as editorial assistant for Sky and Telescope magazine in 1961.

Later, he received his Ph.D. in philosophy from Fordham University in 1963, where he met his future wife, Elena Duverges, a scholar from Argentina. They married that same year.

They moved to Cincinnati to teach philosophy, George at Xavier University and Elena at what was then Villa Madonna College in Northern Kentucky. In 1965 she stopped teaching, and he took a job at Villa Madonna--later Thomas More College--where he taught until he retired in 1999. (Elena joined the Xavier University faculty in 1968, where she taught until her retirement in 2004.) During this time he also taught at St. Pius X Seminary. He chaired the philosophy department at Thomas More at three separate times, for a total of 11 years during his career, and held elected positions in the Kentucky Philosophical Association and the American Catholic Philosophical Association. In a time when self-publishing was largely unknown, George authored and self-published all the texts used in his classes. He also wrote Modes of the Finite, a seven-volume work setting forth his philosophy.

In 1964 George and Elena had their first child, Paul, followed by their daughter Michele in 1967. They have lived in the same house, near Xavier University, since 1964.

In 1966, George received a Fulbright grant to teach two philosophy courses in Spanish at the Universidad del Salvador in Buenos Aires, Argentina. He spoke Spanish, Latin, and some French, with an extensive knowledge of ancient Greek and a good reading knowledge of German and Hebrew. In his later life he translated Plato's Republic as well as the New Testament from Greek, using contemporary, idiomatic English. His translation of the Gospels was titled The Documents of the New Treaty Between YHWH and the Human Race, though it was later published by Edwin Mellen Press as The New Testament: An Idiomatic Translation.

His interest in scripture also manifested itself in studies of the symbolic repetition of words in the Book of Revelation, and in a solution to the synoptic problem. His book The Synoptic Gospels Compared was published by Edwin Mellen Press in 2003.

He was also an author of fiction, writing novels, plays, and poems. An early novel, Acosmia, is a science-fiction story about his son and daughter traveling to the planet Jupiter in 2001. He wrote a series of sonnets for the hours, and a play, Longinus, about a Roman soldier who was present at the death of Jesus. In recent years he completed an interlocking cycle of seven novels that each tell the story of Christ's life from the point of view of a different disciple.

He made most of his writings freely available on the Internet, at his website http://www.fundamentalissues.net.

Catholicism was at the center of his beliefs and he was active in his church. He regularly read and assisted at St. Cecilia parish, and supported a number of Catholic institutions and causes including the St. Peter Claver Latin School and the Ave Maria University. He was an outspoken opponent of abortion and took an active interest in politics. In the 1960s he would have called himself a liberal, and his ideas were considered radical enough to spark a heresy examination during the time he was teaching at Xavier University. (His views were not found heretical.) In later years, however, he viewed himself as a conservative, both in religion and in politics.

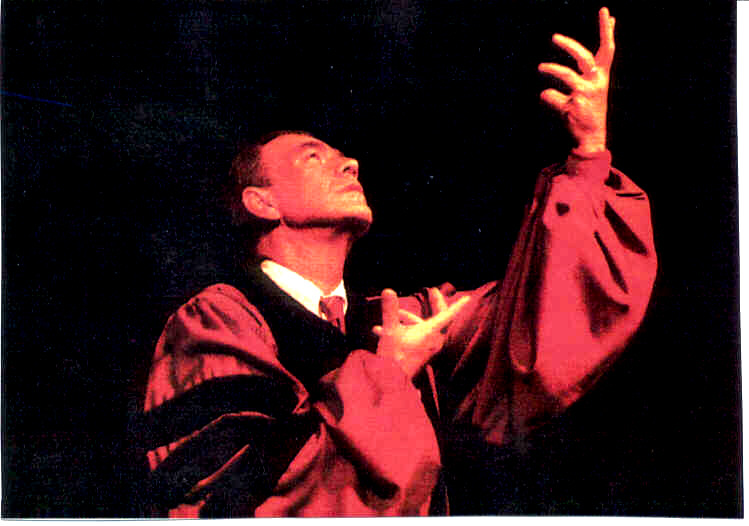

His many interests also included drama. In the late 1970s and early 1980s he received grants to produce videos in which he "interviewed" famous philosophers of the past. He also played Charles Dickens at Saks Fifth Avenue's "Dickens High Tea" in the mid-1980s. In the 1980s and 1990s he would often perform a solo dramatic reading of the Gospel of John and a costumed presentation on St. Thomas More.

He was also an amateur painter, and showed paintings in 1963 at Fordham and in 1967 and 1970 at Thomas More. At his home are many of his paintings, including portraits of his wife, son and daughter, a triptych of St. George, St. Helena, and the Nativity, and a mural of C.S. Lewis' land of Narnia. At one point in his life he took to wood carving, creating a number of sculptures, often with religious themes.

In the 1970s and 1980s he sang in the Cincinnati May Festival Chorus, under such conductors as James Levine, Leonard Bernstein, and Robert Shaw.

In the 1980s he purchased one of the world's first portable computers, an Osborne 1, the size of a small suitcase. He was an authority on the WordStar word processing program and wrote many articles in COGWheels, the newsletter of the Cincinnati Osborne Group. On this computer, he learned desktop publishing before it even had a name.

In his retirement he and Elena loved to travel to Cancún, Mexico. For eighteen years they stayed at the hotel Fiestamericana Condesa several times a year, where they came to be beloved by the staff. During his most recent trip to Mexico, George suffered an acute attack of congestive heart failure that would later prove fatal; the ensuing return to the United States reminded his family of the intrigues and gambits in the mystery novels he read so often. George died doing something that he loved.

A little over ten years ago, in a letter to a publisher, he wrote: "One of my objects in life is to demonstrate that the Renaissance Man is not an impossibility even in the present age. How successful I've been or will be is not for me to judge, of course; but I must say that my life up to this point has been a lot of fun."